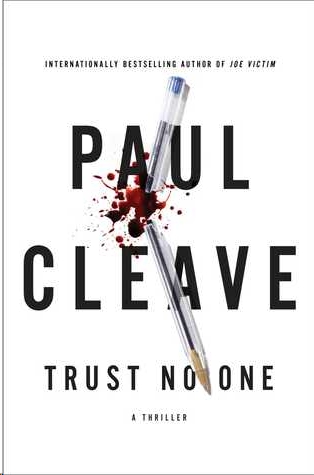

Trust No One

To Miss Roberts—my favorite teacher. Bees?

“The devil is in the details,” Jerry says, and back then the devil was him, and these days those details are hard to hang on to. He can remember the woman’s face, the way her mouth opened when all she could manage was an

oh.

Of course people never know what they’re going to say when their time is up. Oscar Wilde said something about curtains when he was on his deathbed, about how ugly they were and either they must go or he would. But Jerry also remembers reading that nobody knows for sure if Wilde really said that. Certainly he wouldn’t have said something pithy if Jerry had snuck into his house and used a knife to pin him to the wall. Maybe a

hurts more than I’d thought,

but nothing to go down in the history books.

His mind is wandering, it’s doing that thing it does that he hates, that he oh so hates.

The policewoman staring at him has a look on her face one would reserve for a wounded cat. In her midtwenties, she has features that make him think he’d like to be the devil around her too. Nice long legs, blond hair down to her shoulders, athletic curves and tones. She has a set of blue eyes that keep pulling him in. She’s in a tight, black skirt and a snug-fitting dark blue top that he’d like to see on the floor. She keeps rubbing her thumb against the pad of her ring finger, where she’s sporting the type of callus he’s seen on guitar players. Leaning against the wall with his thick forearms folded is a policeman in uniform, an 80s, TV-cop moustache on his lip and a utility belt full of citizen-restraining tools around his waist. He looks bored.

Jerry carries on with the interview. “The woman was thirty, give or take a year, and her name was Susan, only she spelled it with a

z.

People spell things all sorts of weird ways these days. I blame cell phones,” he says, and he waits for her to nod and agree, but she doesn’t, nor does the cop holding up the wall. He realizes his mind has once again gone wandering.

He takes a deep breath and tightens his grip on the arms of the chair and repositions himself to try and get more comfortable. He closes his eyes and he focuses, focuses, and he takes himself back to Suzan with a

z,

Suzan with her black hair tied into a ponytail, Suzan with a sexy smile and a great tan and an unlocked door at three in the morning. That’s the kind of neighborhood Jerry lived in back then. A lot has changed in thirty years. Hell, he’s changed. But back before texting and the Internet butchered the English language, people weren’t as suspicious. Or perhaps they were just lazier. He doesn’t know. What he does know is he was surprised to find her house so easy to get into. He was nineteen years old and Suzan was the girl of his dreams.

“I can still feel the moment,” Jerry says. “I mean, nobody is ever going to forget the first time they take a life. But before that I stood in her backyard and I held my arms out wide as if I could embrace the moon. It was a few days before Christmas. In fact it was the longest day of the year. I remember the clear sky and the way the stars from a million miles away made the night feel timeless.” He closes his eyes and takes himself back to the moment. He can almost taste the air. “I remember thinking on this night people would be born and people would die,” he says, his eyes still closed, “and that the stars didn’t care, that even the stars weren’t forever and life was fleeting. I was feeling pretty damn philosophical. I also remember the urgent need to take a piss, and taking one behind her garage.”

He opens his eyes. His throat is getting a little sore from all the talking and his arm keeps itching. There’s a glass of water in front of him. He sips at it, and looks at the man against the wall, the man who is staring at Jerry impassively, as if he’d rather be getting shot in the line of duty than listening to a man telling his tales. Jerry has always known this day was coming, the day of confession. He just hopes it comes with absolution. After all, that’s why he’s here. Absolution will lead to a cure.

“Do you know who I am?” the woman asks, and suddenly he gets the idea she’s about to tell him she’s not a cop at all, but the daughter of one of his victims. Or a sister. His eyes are undressing her, they’re putting her into a home-alone scenario, an alone-in-a-parking-garage scenario, a deserted-street-at-night scenario. “Jerry?”

He could strangle her with her own hair. He could shape her long legs in all directions.

“Jerry, do you know who I am?”

“Of course I know,” he says, staring at her. “Now would you kindly let me finish? That is why you’re here, isn’t it? For the details?”

“I’m here because—”

He puts his hand up. “Enough,” he tells her, the word forceful, and she sighs and slumps back into her chair as if she’s heard that word a hundred times already. “Let the monster have a voice,” he says. He has forgotten her name. Detective . . . somebody, he thinks, then decides to settle on Detective Scenario. “Who knows what I will remember tomorrow?” He taps the side of his head as he asks the question, almost expecting it to make a wooden sound, like the table his parents used to have that was thick wood around the edges but hollow in the middle. He’d tap it, expecting one sound and getting another. He wonders where that table is and wonders if his father sold it so he could buy a few more beers.

“Please, you need to calm down,” Detective Scenario says, and she’s wrong. He doesn’t need to calm down. If anything he might have to start yelling just to get his point across.

“I am calm,” he tells her, and he taps the side of his head and it reminds him of a table his parents used to have. “What is wrong with you?” he asks. “Are you stupid? This case will make your career,” he tells her, “and you sit there like a useless whore.”

Her face turns red. Tears form in her eyes, but don’t fall. He takes another sip of water. It’s cool and helps his throat. The room is silent. The officer against the wall shifts his position by crossing his arms the other way. Jerry thinks about what he just said and figures out where he went wrong. “Look, I’m sorry I said that. Sometimes I say things I shouldn’t.”

She wipes the palms of her hands at her eyes, removing the tears before they fall.

“Can I carry on now?” he asks.

“If that will make you happy,” she says.

Happy? No. He’s not doing this to be happy. He’s doing this so he can get better. He thinks back to that night thirty years ago. “I thought I was going to have to pick the lock. I’d been practicing on the one at home. I still lived with my parents back then. When they were out I’d practice picking the lock on the back door. I’d been shown how by a friend from university. He said knowing how to pick a lock is like having a key to the world. It made me think about Suzan. It took me two months to figure out how to do it, and I was nervous because I knew once I got to her house the lock might be all kinds of different. It was all for nothing, because when I got there her door was unlocked. It was a product of the day, I guess, though that day really was just as violent as this day.”

He takes a sip of water. Nobody says anything. He carries on.

“I never even had doubts. The door being unlocked, that was a sign and I took it. I had a small flashlight with me so I wouldn’t bump into any walls. Suzan used to live with her boyfriend, but he’d moved out a few months earlier. They used to fight all the time. I could hear it from my house almost opposite, so I was pretty sure no matter what happened to Suzan with a

z,

he would be blamed for it. I used to think about her all the time. I imagined how she would look naked. I just had to know, you know? I had to know how her skin would feel, how her hair would smell, how her mouth would taste. It was like an itch. That’s about the best way to describe it. An itch that was driving me insane,” he says, scratching at the itch on his arm that is also driving him insane. An insect bite, maybe a mosquito or a spider. “So that night on the longest day of the year I went into her house at three o’clock in the morning with a knife so I could scratch it.”

Which is exactly what he did. He walked down her hallway and found her bedroom, and then stood in the doorway the same way he’d stood outside, but this time instead of embracing the stars he was embracing the darkness. He’s been embracing the darkness ever since.

“She didn’t even wake up. I mean, not right away. My eyes were adjusting to the dark. Part of the room was lit up by an alarm clock, part was lit up because the curtains were thin and there was a streetlamp outside. I moved over to her bed and I crouched next to it and I just waited. I’d always had this theory that if you did that, the person would wake up, and that’s what happened. It took thirty seconds. I put the knife against her throat,” he tells them, and Detective Scenario flinches a little and looks ready to cry again, and the officer still looks like he’d rather be anywhere else. “I could feel her breath on my hand, and her eyes . . . her eyes were wide and terrified and made me feel—”

“I know all about Suzan with a

z

,

” Detective Scenario says.

Jerry can’t help it, but he feels embarrassed. That’s one of the cruel side effects—he’s told her all this before and can’t remember. It’s the details—those damn details that are hard to hang on to.

“It’s okay, Jerry,” she says.

“What do you mean it’s okay? I killed that woman and now I’m being punished for what I did to her, to all of them, because she was the first of many, and the monster needs to confess, the monster needs to find redemption because if he can, then the Universe will stop punishing him and he can get better.”

The detective lifts a handbag off the floor and rests it on her lap. She pulls out a book. She hands it to him. “Do you recognize it?”

“Should I?”

“Read the back cover.”

The book is called

A Christmas Murder.

He turns it over. The first line is “Suzan with a z was going to change his life.”

“What in the hell is this?”

“You don’t recognize me, do you,” she says.

“I—” he says, but adds nothing more. There is something there—something coming to the surface. He looks at the way her thumb rubs against the callus on her finger, and there’s something familiar about that. Somebody he knows used to do that. “Should I?” he asks, and the answer is yes, he should.

“I’m Eva. Your daughter.”

“I don’t have a daughter. You’re a cop, and you’re trying to trick me,” he says, doing his best not to sound angry.

“I’m not a cop, Jerry.”

“No! No, if I had a daughter I would know about it!” he says, and he slams his hand down on the table. The officer leaning against the wall takes a few steps forward until Eva looks at him and asks him to wait.

“Jerry, please, look at the book.”

He doesn’t look at the book. He doesn’t do anything but stare at her, and then he closes his eyes and he wonders how life has gotten this way. Eighteen months ago things were fine, weren’t they? What is real and what isn’t?

“Jerry?”

“Eva?”

“That’s right, Jerry. It’s Eva.”

He opens his eyes and looks at the book. He’s seen this cover before, but if he’s read this book he doesn’t remember. He looks at the name of the author. It’s familiar. It’s . . . but he can’t get there.