Two Moons (24 page)

Authors: Thomas Mallon

“Now what’s this you think you’ve seen?” Newcomb asked his dour colleague.

“Probably nothing at all,” said Hall, who was handing Newcomb a piece of paper, if Cynthia’s ears judged the situation right.

“Twelfth magnitude at its elongation!” exclaimed Newcomb. “Why, this looks very much like a satellite.”

Hall murmured something, doubtfully. Newcomb continued to

hypothesize and, Cynthia realized, hope against hope. “Of course, it

is

more likely an asteroid,” he said. Unless—you could almost hear him thinking it—the heavenly body really was an historic discovery made by someone other than Simon Newcomb? “Would you like me to try confirming it?” he asked Hall.

The New Englander politely declined the offer of help.

Newcomb’s nervousness kept showing. “D’Arrest looked hard for a moon, fifteen years ago, in Copenhagen.”

“Yes,” agreed Hall, quietly. “Of course, the power of our new glass can turn up so many things these days.”

“You seem rather casual about this object,” Newcomb declared.

“Well, it’s always best to be doubtful,” said Hall, who by the sound of things was returning to his lunch.

Newcomb swept out into the corridor, ignoring Cynthia and Mr. Harrison. The computer and the clerk signaled each other with raised eyebrows and then returned to their work. Something was definitely afoot, and by the time she got back to her desk, Cynthia felt sure she’d figured it out. Asaph Hall had seen something special last night, and then excited his family with news of the discovery. But the first signs of the phenomenon had probably made themselves known last Saturday night—and upon hearing of them from her husband, the fervent, ambitious Mrs. Hall had hustled her brood into its outdoor petition of the heavens. Hall was now

feigning

calm in front of Newcomb: he had been too agitated not to let slip some news of his twelfth-magnitude observation, but smart enough not to set himself up for ridicule, should the object prove something humbler than a moon.

Later in the afternoon, Cynthia contrived another excuse to roam the building. In the library she found Newcomb dictating correspondence—no doubt more cover letters for more inscribed monographs—to his young dogsbody, Mr. Todd, just back from his New Jersey vacation. In the second or two she could stand nearby, she noticed Newcomb’s difficulty keeping his mind on whatever lines he was dictating. He paced the length of the table, back and forth. Mr. Todd, infected

with his mentor’s agitation, had to apply his blotter to two different mistakes.

“I’ve got to extrapolate the thing’s orbit,” said Newcomb. “That’s all there is to it. I should be doing that right now.”

“It

could

be just an asteroid, sir.”

“It’s a damned moon, Todd. I guarantee you. I don’t think Hall even knows what he has.” His rival’s possible success, not the suspense, was killing him.

Before the day finished, the whole Observatory had sensed the commotion. Admiral Rodgers himself came by Professor Harkness’s desk to work off a flutter of nerves: “I don’t know what Mr. Hall’s engaged in, and I don’t want to know. Not until we’re sure it’s something important.” It mattered not to the superintendent whether the astronomer had seen green cheese or a half-dozen new Suns, so long as it was something

big.

“He’d better be looking for it again tonight,” the admiral said, walking away before Harkness could reply.

Cynthia frowned. She would of course miss any excitement to be had this evening. It was being here in the daytime that kept her in the dark. But just before leaving, she heard Newcomb tell Harkness, “He’ll have his only view of it immediately prior to dawn,” and she realized that, by some peculiar, unspoken protocol, they would all be leaving Hall alone tonight. On her way out, she went into Mr. Harrison’s office and left a note in Hugh’s pigeonhole, knowing—or at least hoping—that he would arrive at 6

P.M.

for the sunspot observations. “Stay late and be watchful,” she wrote. “Mr. Hall may make history tonight.” Perhaps

this

would shake her dear one loose from his lethargy.

Hugh read the injunction an hour or so later, and he did stay much later than he had intended, but only because he fell asleep at the little table near the 9.6-inch refractor. No one came in on him before or after

the hour slipped past midnight and then 2

A.M.

The high-pitched clamor of a mosquito, which hovered near his right ear before biting him on the wrist, roused him briefly, but it took a small, sudden clatter, coming shortly after four from the vicinity of the Great Equatorial, to wake him fully. He decided to investigate on his way out of the building.

“If that don’t take the rag off the bush!” cried Asaph Hall’s helper, George Anderson. Hugh found the two men taking turns looking into the giant telescope’s eyepiece, which they had slid out as far as it could go, probably to diminish the blaze of a bright body obscuring something of greater interest in its vicinity. The pair were too busy to take any notice of Hugh in the doorway.

“It’s a second one,” declared Anderson. “That’s for certain, Professor Hall!”

“Yes,” said the astronomer. “Smaller and closer in.” His quiet voice shook. “I had better make a fuller note.” He hurried, with his observer’s notebook, to a table at the far end of the room, but before he sat down, he dropped to his knees, thanking the heavens for their magnificent piece of self-revelation.

“Aw, now, Professor Hall,” said Anderson, gently scolding. “There’ll be time for that later.” Anderson was embarrassed, but only in a protective way. He had just spotted Mr. Allison taking notice and did not want this young fellow making sport of Asaph Hall with his mates. Otherwise Allison’s presence was no source of bother at all. What rivalrous problem could arise from such a rudderless lad’s being on the scene?

“Come take a look,” said Anderson, motioning him toward the eyepiece. “But you’ll have to be quick about it.”

As Hugh seated himself at the telescope, Anderson and Hall made plans for Professor Eastman and his assistants to measure this second Martian moon with the 9.6-inch during the coming week; the Great Equatorial would keep up the business of confirming the first one’s existence. By tomorrow night, Hugh knew, the Observatory would be a changed place. Like the moons, it would be discovered, and briefly

famous even to men who had never touched a sextant or binoculars. Every scientific here who got in on the act would be flattered and laureled.

Hugh found the smaller of the two specks and held it in his vision just long enough to see that it most definitely

moved,

like something alive, with respect to the glaring orange circle. Stunned in spite of himself, he felt his own light fizzling into darkness and inconsequence.

“This great triumph, which will go down into history along with Herschel’s discovery of Uranus and Leverrier’s prediction of the existence of Neptune—is purely American.” Commodore Sands put a flourish into his recitation of the last three words of this newspaper encomium from the stack of cuttings that had accumulated in the Observatory’s library. On the afternoon of Wednesday, the 22nd, he had come to join the astronomers for a small celebration. They were catching their breath after five spectacular days.

“Here’s a card from my friend Reeves in New York,” said young Mr. Todd. “ ‘Congratulations on those lunar appendages to Mars. But what am I to do with that astronomy they tried to teach me at Amherst?’ ”

Everyone but Simon Newcomb gave a chuckle. He had spent the past few nights confirming Martian observations and making measurements with Professor Harkness, and while he could hardly admit it here, certainly not in front of Admiral Rodgers, he had had quite enough of little Deimos and Phobos. That’s what they were now called—Homer’s names for Mars’ attendants, rendered more aptly in translation to the current national scene: Panic and Fear. The Great Equatorial would be trained on the satellites through the middle of October, after which they would disappear from even that instrument’s huge eye for another two years.

“I can remember when she was delivered,” the commodore said

about the fantastic telescope that had made the find. Newcomb, too, could recall the November day in ’73 when the clock-driven Cyclops had finally arrived—and could rue the day when he had relinquished its charge to Hall.

No one would ever again lord it over Asaph and his wife. Since Saturday night the rest of the scientifics had been asking

permission

to join Hall and Anderson in the dome, as if the 26-inch were the two men’s personal plaything instead of United States government property. For all this glory, Hall was said to be hopping mad at Newcomb, since the first newspapermen coming around to hear about the discovery had asked to see the only astronomer they’d ever heard of, and Simon Newcomb had obliged them by saying that

he’d

realized the true nature of what Mr. Hall had stumbled upon before Mr. Hall himself did.

One could argue that they were everyone’s moons now. Observatories from Missouri to the middle of Europe had been cabled or mailed an announcement that Rodgers had had run off at the Government Printing Office and gone to pick up in his own carriage. A special letter had been hand-delivered to the landlocked Secretary of the Navy.

Mrs. May’s presence at a social gathering of the men was considered unsuitable, so she remained at her desk, regarding the sudden surfeit of numbers about Deimos and Phobos. The larger moon was 14,500 miles away from Mars, the smaller a mere 5,800, hardly the distance from here to London. Professor Eastman and Henry Paul, measuring Phobos with the 9.6-inch, thought it no more than seven miles across. Cynthia could imagine herself striding it from end to end in under three hours, though she supposed she’d collapse from motion sickness before finishing: the little satellite raced round Mars every seven hours and forty minutes, more than a thousand times every Earth-year. The other moon was a bit slower, but still quite a traveler.

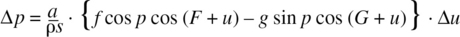

All right, she said, rolling up her cuffs, where ρ is the distance of the planet from the earth, then

“Excellent, Mrs. May,” said the admiral, who’d come up behind her.

“She never disappoints,” added Professor Harkness, placing a piece of cake from the party beside her scratch pad.

“Thank you,” said Cynthia.

“Wonderful to see every man pulling his weight in this affair,” said Rodgers. “Every woman, too, Mrs. May, excuse me. No, there’s no time for slacking. And tell me, if you will, Mrs. May, how is Mr. Allison feeling?”

Their friendship was an open secret, looked upon as one more peculiarity in Mr. Allison’s feckless life. If he were properly robust and ambitious, he would have a comely young girl, not this scrawny widow. For a few moments, over the weekend, Cynthia had hoped the Observatory’s sudden luster would take the admiral’s pressure off Hugh, but something nearer the opposite now appeared more likely. Rodgers had had his breakthrough and would drive them all up from the swamp of Foggy Bottom if it was the last thing he did.

“Mr. Allison is only a bit under the weather, Admiral. I’ve promised to take him some broth, and I’ll give him your good wishes when I do.”

“Yes, Mrs. May, please do just that,” said Rodgers, who now ran off to consult with Mr. Harrison about arranging some hours for the moons to be put on public view.