Two Moons (27 page)

Authors: Thomas Mallon

Before the day was out, Simon Newcomb had asked Mrs. May if she would consider joining him at the Almanac Office for a salary equal to the one she was now paid, and with the opportunity, enjoyed by all the Almanac’s computers and copyists, of working at home. “Thank you, Professor Newcomb,” she’d responded to this man who hadn’t the slightest idea of how people like herself actually lived, “but I can’t think of any more awful privilege.” His startled reply—“Very well, then”—was no doubt the last set of words she would ever hear from him.

Then Friday afternoon brought a second offer of employment, or at least a reprieve. Admiral Rodgers, so occupied with trying to dispel malaria’s influence, suddenly realized he had to deal with the abrupt lifting of Newcomb’s. Aware of his shorthandedness, as well as how unsympathetic it would look to remove a young malarial astronomer at the very moment the Observatory was soliciting congressional pity, the admiral informed Hugh that he could stay on for a while after all. “You will continue working with Mr. Todd, not just on the sunspots, but on his trans-Neptunian search.” Though he took care not to say it, the admiral hoped that pairing Allison and Todd might lead to the sort of teamwork, or rivalry, that could in turn lead to another spectacular like the moons. Rodgers’s whole communication to Hugh had lasted less than a minute, before he and Mr. Harrison were off to deal with one more set of plumbers and plasterers proceeding with the peculiar task of making the present Observatory look as spruce as possible for any powerful visitors who might be able to help get it torn down.

Now, two days later, as Hugh and Cynthia approached the naval academy’s main gate via Hanover Street, she rehearsed all these events, as well as her renewed fantasies, in the privacy of her imagination. She

would buy dress shirts for him at Thompson’s; they would have an 8 percent interest account at the Riggs Savings Bank; each night their little son would wave good-bye to his papa as he went off to look at the stars from some new, “healthful location.”

It was all nonsense, and she loathed herself for entertaining it. The academy’s Lover’s Lane, down which they now walked, with Hugh discoursing upon every tree and flagstone, was really still the thinnest of ice, cracked with the perils of further illness and renewed disapproval by the admiral. And yet, she could not stop herself from thinking that she might not need Conkling’s help after all. What if, before she was in too deep, she just avoided another encounter, allowed him to go back to Mrs. Sprague or some other diversion as he brought forth political apocalypse?

They entered the old Government House library, where Hugh’s meeting, arranged several days before Friday’s events, was scheduled to take place. He had been maddeningly merry in withholding its purpose from her, teasing out the possibility it involved some new, sensible ambition, before hinting that, after all, it probably didn’t. She had been, until they boarded the train this morning, fearful of watching him confide his “projection” scheme to another scientific, and after he started jabbering, she had begun to worry that he might not be able to sustain coherence on

any

subject, let alone his vision.

Hugh and the man he was here to see recognized each other by their conspicuous youth. It turned out, during their opening courtesies, that Mr. Albert Michelson, an instructor of physics at the academy, was even three years younger than Mr. Allison. A childhood emigré from eastern Europe, he had an accent more like the American West than Poland, the result of an upbringing in Virginia City, Nevada.

“Admiral Porter is up in Newport inspecting torpedo stations,” Michelson explained. “This library is really his domain, but he’s not around to see us trespassing over it.”

“Ah, Newport,” said Hugh. “Where you might all still be had things turned out differently.” (He had learned only during today’s

train ride that the naval academy had relocated to Newport for the duration of what Cynthia still called, to his amusement, the “rebellion.”)

“Yes,” said Michelson, smiling at the possibility. “But I can tell by your voice that you would have been called home to join the other navy.”

“Weren’t we lucky to have been too young for it!”

Michelson might be more grave in his manner, but Cynthia observed a quick rapport between the two boys, and was relieved to see Hugh, even amidst the pleasantries, making an effort to concentrate.

“Mrs. May,” said Michelson, once Hugh had introduced her, “that is my wife over there—Margaret.”

Cynthia waved at the pretty young woman who sat across the room wearing a sweet expression and a frock that bespoke approaching maternity. The men’s clear expectation was that Mrs. May would go off and join this other member of the sex, but Cynthia took a seat between the two of them.

“How are you feeling?” a now-awkward Michelson asked Hugh.

“Quite all right. A bit of late-summer languor. It was really nothing.”

“They had me as a watch-officer on the

Constitution

for most of the last few months,” said Michelson, who himself looked none too robust. “Nothing but dried apples to eat most of the time.” After a pause, he asked, “So, did you learn of me from Professor Newcomb? I’ve heard that he’s interested in the speed of light as well.”

“Only in the hopes of outrunning it,” said Hugh. “No, I learned of your interests through our friend Jack Cass.”

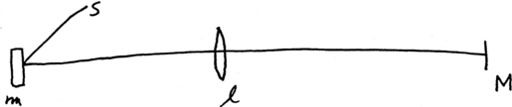

“Oh,” said Michelson, recognizing the name of Hugh’s onetime Cambridge colleague. “Well, I thought we might as well come here instead of to my laboratory, because so far all I have is a drawing. As you can see,” he added, holding up a pencil and managing to smile at Cynthia, “it’s very portable.” He began making a diagram in the margin of a newspaper:

Hugh nodded as Michelson laid down each line. He knew, before the other man even said it, that

s

was meant to represent the light source;

m

a revolving mirror;

l

a long-focus lens; and

M

a plane mirror.

“Tell me,” said Hugh. “If you’re successful, how far off do you expect your results to be from Foucault’s?”

“Oh, not much at all. He was very close, within a few thousand miles per second, I should think.”

“That’s good,” said Hugh, with a peculiar delight that Cynthia and Michelson both noted, the latter with some perplexity.

Cynthia rose and excused herself and said she could not wait a moment longer to talk with Mr. Michelson’s clearly charming wife. She’d been determined to monitor Hugh’s demeanor, and she’d found it less erratic than she’d feared. But she didn’t have the nerve to hear any more of what he might now say to Michelson. If he didn’t start in on his vision, what else

would

he speak of?

Twenty minutes later, she and Hugh were back outside the academy’s gates, walking down Annapolis’s wavy brick sidewalks. He was now quite silent. With her palm gently brushing the telegraph poles they were passing, she wondered how anyone could imagine a need to project himself beyond the distances and speed these wires afforded. Strung under the sea, they could convey even Mary’s Costello’s words to England and France.

He slipped his arm around her waist. “Did Mrs. Michelson resent your lack of interest in her baby?”

“Oh,” said Cynthia, laughing as gaily as she could. “Do you think it was so apparent?”

What would he say if he knew the truth? In the bed on High Street he had ceased withdrawing from her because he thought the press of her hands on his back a wordless reassurance that there was no risk of conception; that they needn’t trouble themselves with anything but increasing their mutual pleasure. She had never used the device. But, however silently, she

was

troubled—by the thought that his misperception might, in a roundabout way, be true; that there was something wrong; that there

was

no risk of a baby.

“Tell me,

please,

” she said, “that all this conversation with Mr. Michelson is applicable to finding a trans-Neptunian planet for the admiral.”

He didn’t hear her request. Once more, he had started talking with the rapidity of an engine. “Would you like to go to Philadelphia soon? We could stay with my hateful sister. A quick trip, just long enough for me to see about some equipment. Obtaining the machinery may be the hard part.”

“I don’t want to hear even the easy part,” she said.

“Of course you don’t,” he replied, kissing her neck.

There was a new popular misconception in Washington that, if one held a mirror up to Mars, one would see Deimos and Phobos, no matter that they were invisible to the naked eye. It was a trick of optics, of course; a cheap mirror rendered multiple, diminishing images of the planet itself, an astral body that Cynthia, as she looked into her own mirror to brush her hair on Monday morning, the 24th, would be content never to see again. The new moons had made for so much work at a time when so many people had fallen sick that the healthy ones, like herself, were woefully tired. Professor Harkness had instructed her to take the day off, and she was obliging him. She had risen an hour later than usual, then brought a slice of bread and the newspaper back up to her room. Keeping one eye on the

Star

while brushing, she noticed

that the standoff between Conkling’s men and the President continued. Mr. Arthur was meeting with Secretary Sherman at the Treasury and, no doubt as Conkling wanted, resisting any compromise.

MADAME ROSS.

507 11TH ST.

THE CELEBRATED ASTROLOGIST

AND CLAIRVOYANT.

CURES ALL DISEASES INCIDENT

TO FEMALES.

CONSULTATIONS

STRICTLY CONFIDENTIAL.

LADIES $1, GENTLEMEN $1.50.

She spotted this advertisement for one of Mary Costello’s rivals not far from another promising “Happy Relief to Young Men from the Effects of Errors and Abuses in Early Life. Manhood restored. Impediments to marriage removed. New method of treatment. New and remarkable remedies.”

She tried counting the occasions of her intimacy with Hugh. She wound up using her fingers, not from a sudden loss of mathematical prowess, but because she kept pausing over some particular memory of each night and losing track of the tally. The occasions were too few in number to constitute a reliable scientific sampling, but something—she felt more and more certain—was wrong, and it had nothing to do with any “errors and abuses” of his. She had been cursed twice, as regularly as ever, since her first night in the bed on High Street. And yet, at each monthly sign of her apparent fertility, she began hearing the voice of her mother—in particular, the words Ellen Lawrence had said while helping her stagger to a chamber pot the first time she’d bled after Sally’s delivery:

You will never again have to worry about that.

Her mother had not been talking about the bleeding, but the nearly fatal pain of the child’s Cesarean birth. The reassurance had been echoed,

Cynthia could now recall with some effort, by the cluckings of Mrs. Sidney Robinson, a busybody neighbor who late in the war often foisted herself upon Mrs. Lawrence and who that day had sat in a corner of the room marveling over “modern miracles.” At the time, Cynthia herself had been too weak and indifferent to think of anything but collapsing back into bed and cradling her undersized, too-quiet baby girl.

But this morning, thirteen years later, she could think of nothing but Mrs. Robinson’s words, and when she completed dressing, she went immediately downstairs and out of the house. The morning was so hot, and her pace to Mary Costello’s so fast, that she ought to have been carrying a fan, but waving one on the street always made her feel like an insect. She was perspiring heavily by the time she reached Third and D, where the astrologer was ushering out one embarrassed young gentleman, no doubt a troubled office-seeker, and showing in another—Conkling’s lieutenant, who after taking a good look at Cynthia, went off with the latest portents to be telegraphed to his boss in upstate New York.