Ultimate Baseball Road Trip (28 page)

Read Ultimate Baseball Road Trip Online

Authors: Josh Pahigian,Kevin O’Connell

During the final years of the Expos, San Juan, Puerto Rico’s Hiram Bithorn Stadium became a sort of home away from home for the Expos as MLB sought to showcase the game to Latino fans. Before the Expos’ first game at Hi Bithorn in 2003, Orlando Cepeda threw out the first pitch. Then pop star Marc Anthony sang the US and Puerto Rican National Anthems, which were followed by the Canadian anthem. Four flags flew at the stadium—those of the United States, Puerto Rico, Canada, and San Juan. When it finally came time to play ball, the Expos trounced the Mets 10-0 before 17,906 screaming fans. But most observers agreed that Hi Bithorn was not fit for Major League competition. At

just 315 feet down the lines and 360 to the power alleys, the park quickly distinguished itself as a hitter’s paradise. In the Expos’ first sixteen games at Hi Bithorn, there were sixty-three home runs. If players “went yard” at that rate during the course of a full season, San Juan’s ballpark would project to yield 319 long balls in eighty-one games, or sixteen more than Coors Field surrendered in 1999 when the Rockies and their opponents established the record for most dingers in a park. Hi Bithorn’s other distinguishing feature was its bright green-colored artificial turf, which quickly had fans all across America scratching their heads during ESPN’s

SportsCenter

and trying to adjust the tint on their TV sets.

But San Juan was just a stop along the way to D.C. And no one ever suspected it would be more than that. The history of baseball runs deep in Washington and for that reason we think it was a fit place to locate the Expos, even if we disapprove of the methods by which the game’s overseers brought about this development. While in the first edition of this book we divided the history of the Washington Senators between the two current MLB teams the Senators spawned, the Minnesota Twins and the Texas Rangers, now we are happy to properly display D.C.’s unified baseball history in the introduction to a chapter dedicated to the city’s resident team.

Nationals Park is actually the second park so-named that a Washington team has utilized. National Park was the original name of Griffith Stadium and was the home of the Washington Nationals/Senators that played baseball at its location near Florida Avenue beginning in the early 1900s. Previously, Florida Avenue was named Boundary Street, and the ballpark was called Boundary Field, home to the American Association incarnation of the Senators during the 1890s.

On the site of Griffith Stadium there had previously existed several ballparks under many names dating back as far as 1892. For a number of years the wooden ballpark was known simultaneously as National Park, League Park, and American League Park, depending on whom you asked. And we thought politics in Washington were confusing! After the park with three names burned down in 1911, it was rebuilt with concrete and steel, and was once again named National Park. Then in 1920 it was renamed Griffith Stadium in honor of Senators owner Clark Griffith.

But Griffith Stadium wasn’t a stadium at all. It was a clunky old ballpark that at its peak seated only thirty-two thousand fans. Perhaps the most noticeable of the ballpark’s many quirks was a huge center-field wall with an irregular indented and squared-off segment that cast two right angles protruding into an otherwise regular field of play. Beyond this thirty-foot-high wall were five houses outside the park, whose owners had refused to sell their property to Griffith when the ballpark was being built. And so the backyards of these homes were just beyond the wall. In one backyard a huge oak tree’s branches and leaves rose up over the fence and into the field of play. According to lore, Babe Ruth lodged a few home runs in that tree. A flagpole also stood atop the fence, to add to the irregularity of it all. Plus the park was simply shaped funny. Not only were its bullpens in fair play, but the left-field wall was 407 feet from the plate, while right was only 328 feet.

Walter “the Big Train” Johnson’s career with the Senators was one of the franchise’s great individual success stories and one of much team disappointment. In twenty-one seasons from 1907 through 1927, Johnson won 417 games, struck out 3,509 batters, and authored an amazing 2.17 ERA. But despite boasting one of the most dominant pitchers of the era, the Senators managed only two trips to the World Series, winning the October Classic only in 1924.

President John F. Kennedy threw out the first pitch for the Senators at Griffith Stadium on Opening Day 1961, before a 4-3 loss to the White Sox. The Senators’ incarnation that would later become the Texas Rangers only played one season at Griffith Stadium. Newly built D.C. Stadium was ready by 1962, and the Senators won the first game at

the cookie-cutter, 4-1 over Detroit. The 1962 All-Star Game was also held at D.C. Stadium, resulting in a 3-1 National League victory. The park was renamed RFK Stadium in 1969, in honor of the late Robert F. Kennedy. Ted Williams managed the Senators of 1969 to a winning record—the first in their history as an expansion franchise—and won AL Manager of the Year honors in the process. And the All-Star Game was held at RFK again in 1969, resulting in another NL victory, this time by a score of 9-3.

A popular old vaudeville saying went, “The Washington Senators: first in War, first in Peace, and last in the American League,” as the Senators were more often at the bottom of the standings than the top, and quite often the butt of jokes. But Griffith Stadium did manage to host three World Series: in 1924, 1925, and 1933. The 1924 set proved successful for the Senators, when in Game 7, New York Giants catcher Hank Gowdy tripped over his own mask and missed an easy pop-up. This gaffe set the stage for a come-from-behind win for the Senators when Earl McNeely chopped a grounder over the head of third baseman Fred Lindstrom to score the winning run in the bottom of the twelfth inning.

A couple of interesting traditions also began at Griffith Stadium. The first was in 1910, when President William Howard Taft threw out the first pitch of the season. During the remaining time the Senators played in Washington, D.C., the president was always on hand to toss out the first ball of the season. During Washington’s long MLB hiatus, this tradition became a Baltimore Orioles’ hallmark, but in recent years presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama resumed the tradition of signaling the start of each new season by tossing a first ball at a ballpark inside the Beltway.

The seventh-inning stretch was also born at Griffith with Taft playing a starring role in the tradition’s origin. According to baseball lore, the portly president stood to relieve some tightness in his back during the middle of the seventh, and the crowd, thinking he was about to leave, rose to salute him. When Taft merely rolled his shoulders a few times, the other fans did the same, then followed his lead and sat back down to watch the final two innings.

For all the fervor that was created to bring MLB back to D.C., the team’s lack of success has resulted in lackluster attendance throughout their early years in town. In their first season at broken-down RFK, the Nats drew 2,731,993 fans in 2005. They narrowly surpassed two million in 2006, but that number dipped below two million in 2007. The team’s first year at Nationals Park saw a slight increase to 2,320,400 fans in 2008. But the team couldn’t maintain a place on the high side of the two million mark in the years after that. The numbers for the first three years in the new ballpark were the worst since Great American opened in Cincinnati in 2003.

Trivia Timeout

Congressman:

Who hit the only fair ball out of Yankee Stadium? (Hint: He played for a while in Washington.)

Junior Senator:

Who holds the record for most career home runs in a Nationals or Senators uniform?

Senior Senator:

Of the four Montreal Expos who had their numbers retired at Olympic Stadium, which have their numbers now hanging at Nationals Park? (Hint: It’s not all four.)

Look for the answers in the text

.

Nonetheless, in its brief history, Nationals Park has seen more than its share of historical happenings. The first MLB game at Nationals Park was played on March 30, 2008, between the Nats and Atlanta Braves, and drew the largest ratings of any opening night game on ESPN. President

George W. Bush threw out the first pitch as the hometown nine disposed of the Tomahawks 3-2.

Josh:

I suppose you support the theory that the stylized curly “W” of the Nats is some sort of conspiracy homage to “W” himself.

Kevin:

Actually, I thought they lifted it from Walgreens. The Pope visited Nationals Park on April 17, 2008—not

John Paul, but the one after him—and said a quick Mass for forty-seven thousand. Before Opening Day 2009, legendary Phillies broadcaster Harry Kalas collapsed at Nationals Park and was later pronounced dead.

Randy Johnson hurled his three hundredth win at the park on June 4, 2009, while a member of the Giants. Stephen Strasburg, perhaps the most hyped pitching prospect to yet play the game, made his debut at Nationals Park on June 8, 2010, when he went seven innings, gave up just two hits, and struck out an eye-popping fourteen Pittsburgh Pirates. Additionally, Albert Pujols knocked his four hundredth dinger over the right-field wall at Nationals Park, making him the fastest player to ever reach the mark.

Josh:

Actually, he was just the fastest in terms of how many seasons it took. Name the two players who were younger.

Kevin:

One of them’s a Mariner. Griffey, right?

Josh:

Both of them were M’s, actually. Alex Rodriguez was the other, you dolt.

Kevin:

Yeah, I stopped watching him when he went to Texas.

As many new parks are doing, a tiered approach to pricing results in fluctuating ticket prices depending upon the relative attractiveness of the Nationals’ opponent and the time of year. Thus, home dates are deemed Prime, Regular, or Value games.

Kevin:

This casts no aspersions on the teams labeled as “value” game teams.

Josh:

Of course not.

Kevin:

So it’s no coincidence the Diamondbacks are a “value” all across the league.

Josh:

Capital-ism. Don’t you love it?

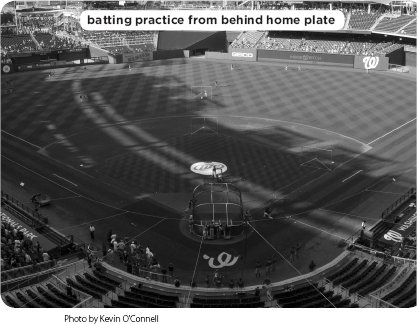

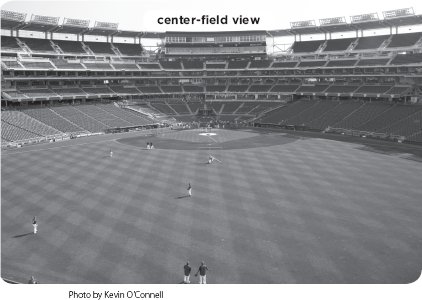

A low-angled, long deck without much foul territory puts plenty of seats in the lower bowl close to the action. And the stacked design of the upper levels does not contribute to any overhang issues even for the top seats in the bowl, all the way up to row UU. Sight lines are good all the way around the Field Level, and the prices match the quality accordingly. The only mistake that they made as far as we can tell on the Field Level is that the view from the concourse is blocked as you walk behind home plate. This is the case at another recently designed Populous park too—Citi Field in New York—and we don’t like it.

SEATING TIP

As soon as the gates officially open, the main ticket office sells $5.00 Grandstand tickets that allow access to any part of the ballpark. The tickets do have a section and seat number attached to them, but there are plenty of places from which to view the game where you don’t have to be sitting in your own seat. As is the rule with other deals like this, getting there early enough to get the tickets is key, because the line for cheap tickets gets long. The more time you spend waiting in line to buy the tickets, the more people who have tickets in hand will go through the gate to sit down in a seat that should have been rightfully yours. So plan ahead.