Ultimate Baseball Road Trip (89 page)

Read Ultimate Baseball Road Trip Online

Authors: Josh Pahigian,Kevin O’Connell

We also tried the

Toasted Ravioli,

which is a real treat, and the

Beer-Battered Mozzarella Sticks

(more dairy!),

and they were good as well. But if you have to choose between them, go for the Toasted Ravioli. You just can’t get that at many places.

The

Grab and Go

stands offer an assortment of fresh salads and fruit cups as well as

Cheese Curds.

We didn’t try the curds. Our trip to Toronto had taught us to be wary. But they do have

Poutine

at Miller Park if you like curds and fries.

Josh:

Ha! “Grab and Go” would be a great name for a serial groper.

Kevin:

For some reason I found your comments much funnier on our first baseball trip.

Josh:

That’s because you grew up, while I’m still working on it.

Well, you’re at Miller Park, so you might as well embrace Miller or MGD, because that’s the house brew. On the plus side, the 24-ounce cup is a fistful. Buy two and you should be all set for at least a couple of innings. Specialty stands, meanwhile, serve regional favorite

Leinie’s Draft

(courtesy of Leinenkugel Brewing Company in Chippewa Falls). By the way, Leinenkugel offers a variety of other great beers, if you get the chance to sample them anywhere else in the city.

HAVE A BARREL OF FUN

Now here is a Brew City tradition that has survived from the County Stadium era. During the Seventh Inning Stretch, fans enjoy a rousing rendition of “Roll out the Barrel.” Ushers get into the spirit, dancing a two-step while the crowd cheers. Unfortunately the barrel isn’t being rolled out, it’s being rolled up. Shortly after the music ends, all beer sales cease for the day.

Kevin:

We still have a cold six-pack in the parking lot.

Josh:

Yes, but we’re not leaving until the final out.

Kevin:

I know. I know. Just thought I’d remind you.

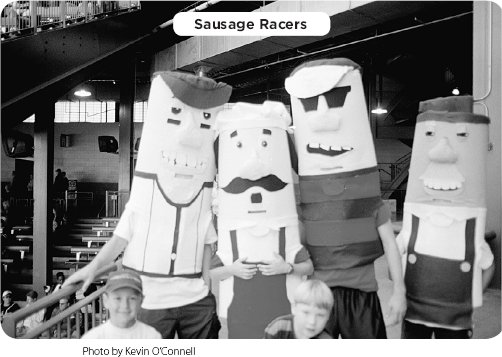

Miller Park stages daily Sausage Races in the middle of the sixth inning, featuring a Brat, Polish, Italian, Chorizo and Hot Dog. Sometimes, on Kids Days, child-sized Wienie Links take part too. The assorted meat mascots make their way from the video screen to the field. Both times we’ve visited Miller the Brat won, which made a lot of sense to us. It’s the best of the packed meats the stadium offers. During a game in 2003, Pirates first baseman Randall Simon knocked over one of the sausages with his bat. While the YouTube video of this looks as if Simon was trying to behead the sausage racer, this was really a case of a joke that went bad. But nevertheless, Sausage Gate was born, causing strife between Pittsburgh and Milwaukee for years to come.

Hey, what gives? Bernie Brewer, the team’s infamous drunk from the old days, used to live in a chalet and slide into a vat of beer. Now Bernie lives in an air-conditioned pad on the third level and slides down to … (wait for it) … a home-plate-shaped platform on a lower level.

Bernie still casts hexes on opposing players and hangs Ks when Brewer pitchers strike out opponents. But what happened to the old sud-soaked drunk we used to love?

Josh:

He cleaned up his act. It was time.

Kevin:

You East Coasters always have to be so politically correct.

Josh:

It was time for Bernie to grow up.

Kevin:

Exactly. He used to throw up all the time!

Josh:

I said ‘grow,’ not ‘throw.’

Kevin:

Oh.

Sports in the City

Milwaukee Sports Walk of Fame

Along 4th Street between Kilborn and State is the Milwaukee Sports Walk of Fame, which features any sports figure remotely related to Milwaukee. Natives who played for teams in other cities and players who played for the teams of Wisconsin are honored here. Bronze placards pay tribute to such greats as Earl L. “Curley” Lambeau, Oscar “the Big O” Robertson, Elroy “Crazy Legs” Hirsch, and the immortal Vincent T. Lombardi. Baseball greats include Spahn, Aaron, and Uecker.

Harley Davidson motorcycles are made in Milwaukee and a biker dude takes the game balls onto the field with a Harley before each game. The motorcycle manufacturer has been headquartered in Milwaukee since its founding in 1903.

The “Safe Ride Home” program seems like a necessity for a number of reasons. The park is isolated by its own off-ramps from the highway, and other than the bus, there is no way in or out except by car. The team name is the Brewers and the park is named after a major beer label. Tailgating is encouraged (in true Wisconsin fashion) and the team mascot is a reformed brewmeister still struggling to get his life on track. The team plays “Roll Out the Barrel” in the middle of the seventh. The beer culture that pervades Milwaukee is celebrated at the park, so the team offers fans free rides home if they get sufficiently tanked. The rules state that a cab will be called for you at the discretion of management. Head to the Guest Relations Office on the Field Level behind home plate for the staffers there to see if they think you’re inebriated enough to qualify.

Josh:

If you’re turned down, can you have a few more beers and try again?

Kevin:

I don’t see why not.

Josh:

Well then, this is kind of like a

Mr. Belvedere

episode when Kevin abused Bob Uecker’s offer to drive him home if he ever called drunk at a party.

Kevin:

Will you please stop with the

Belvedere

stuff.

There is no greater athletic supporter (just kidding, Bob) in Milwaukee than “Mr. Baseball,” who has been the voice of the Brewers since 1971. A Milwaukeean who made good (to the tune of a .200 lifetime batting average!), Uke turned a very mediocre catching career and larger-than-life personality into great celebrity. Because Uke is the radio announcer for the Brewers you won’t be able to hear him from your seats, so cruise into the bathroom where he can be heard all game long. How appropriate (just kidding again). But seriously, aside from being an actor, entertainer, and fabulous storyteller, Uke is a very solid radio man. In July of 2003 he was honored with the Ford C. Frick Award and entered the broadcaster’s wing of the Baseball Hall of Fame. When a member of the home team hits a home run, Uecker’s trademark homer call flashes in lights above Bernie Brewer’s left-field dugout. “Get up! Get up! Get out of here! Gone!” it says, then Bernie hops on his slide to begin his celebratory descent to the home plate shaped platform below.

Cyber Super-Fans

- Bernie’s Crew

www.jsonline.com/blogs/sports/fanblogs/berniescrew.html

This

Journal Sentinel

blog broke word of the Zack Greinke trade in December 2010. - Brew Crew Ball

www.brewcrewball.com/

The mug’s always frosty, the fan-confidence poll is always hoppy and our friend Kyle Lobner is one of the hardest-working blog editors we know. - Disciples of Uecker

http://disciplesofuecker.com/

Offers hard-hitting game-analysis all season long.

We out “Ueckered” the “Uecker Seats”

After buying $1.00 “Uecker” tickets, we met Glenn Dickert, who proved to be our guardian angel.

Kevin was at Helfaer Field, taking pictures and talking to strangers as he usually does on road trips. “One of the best ways to learn about a ballpark,” he has said on countless occasions “is to talk to ushers and season-ticket holders. After all, they’re here every day, the lucky bastards.” Yeah, yeah, yeah. Heard it all before.

Glenn, a particularly kindly usher and former math teacher, was working at the little ballpark outside the big one when Kevin stopped by, and he fed Kevin all kinds of factoids about Miller Park. While gabbing, Kevin got around

to handing Glenn our cheesy homemade business card, and telling him about the book. Glenn was genuinely excited.

“Where are your seats?” he asked.

“We had to buy Uecker seats,” Kevin said, “We didn’t plan ahead, and the other cheap seats were sold out.”

“Ah, that’s a shame,” Glenn said. “You won’t get any good pictures from up in the rafters.”

“Probably not,” Kevin lamented. “But we thought we’d walk around early and take some shots.”

“Well, I’ll tell you what,” Glenn said, with a fatherly glint in his bright Wisconsin eyes, “I’m the usher behind home plate. Come on down after the third and we’ll see if we can put you in some good seats.”

We thanked our prospective benefactor and promised to meet him later in the day. After doing our legwork for the book—i.e., eating a half-dozen sausages each—we settled briefly into our Uecker Seats.

“I must be in the front row,” Josh yelled.

“He missed the tag!” Kevin cried.

“Wesley, did you steal Mr. Belvedere’s girdle,” Josh hollered.

When we met up with our new friend Glenn, he walked us down to the seats we had always dreamt of. Seats 1 and 2 of Row 1 right behind the plate!

“We

are

in the front row!” said Josh.

“We out Ueckered the Uecker seats!” Kevin chortled.

“We pulled a reverse-Uecker.”

Take it from us, the folks in Milwaukee are the nicest people you’re likely to meet on your trip. Thanks, Glenn!

MINNESOTA TWINS,

MINNESOTA TWINS,TARGET FIELD

Outdoor Ball in the Land o’ Lakes

M

INNEAPOLIS

, M

INNESOTA

290 MILES TO FIELD OF DREAMS

340 MILES TO MILWAUKEE

410 MILES TO CHICAGO

440 MILES TO KANSAS CITY

I

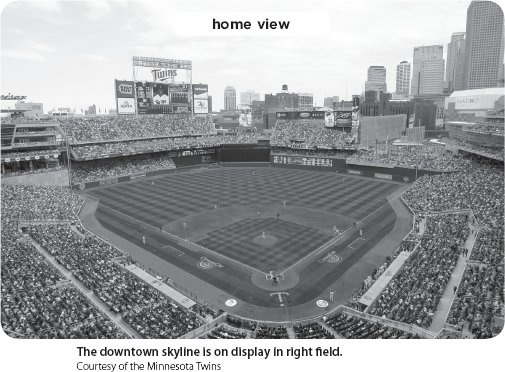

t took the Twin Cities longer than just about every other big league market to embrace the turn-of-the-century stadium construction wave, but with the opening of gorgeous Target Field in 2010 the Twins finally got on board. And did they ever! With the eagerly anticipated opening of Target Field, the dome-bound fans who were forced to suffer through the Metrodome’s three-decade reign finally breathed a big deep breath of fresh air. It was a long wait, but it was worth it. After observing the successes and foibles of new stadium projects in other cities, the Twins got Target Field almost exactly right. Besides offering a natural playing surface, sweeping views of downtown, and an open-air experience, the park delivers a focus on the field so the game—which was sometimes obscured by the acoustic and aesthetic realities of the facility at the Twins’ previous home—can stand front and center.

The fact that this sparkling yard ever came to be is a credit not only to the baseball cunning of a shrewd front office that thrived competitively for a decade despite its antiquated facility, disaffected owner, and payroll measuring a fraction of larger market clubs’, but also to a local fan base that consistently turned out en masse at the Dome. There was a time, and it wasn’t that long ago, when the Twins were on baseball’s endangered species list. Contraction of the team loomed as a real—even likely—possibility in the early 2000s. And if Bud Selig and then-Twins owner Carl Pohlad had had their way, it would have come to pass. But a court ruling in 2001 staved off the dissolution of the Twins, and by extension, Expos, just as the Twins were to begin a ten-year run of excellence during which they finished first or second in the AL Central eight times, while racking up six division titles. Thanks to a bevy of homegrown players that arrived just in time to resurrect the franchise, the team emerged from the doldrums of the waning years of Tom Kelly’s leadership to thrive under new manager Ron Gardenhire. Products of the farm system like Johan Santana, Justin Morneau, Joe Mauer, and Michael Cuddyer helped the Twins assert themselves as a perennial division heavyweight. And the fans turned out to watch, making the team a middle-of-the-pack attendance finisher each year. In short, the team’s success and fans’ enthusiasm made the notion of contracting the team seem ridiculous. And so, the guardians of baseball’s gates called off the dogs, opting instead to leave the Twins alone and move the Expos to Washington.

Ironically, though, just as the Twins’ successes afield and at the gates kept the franchise viable, those factors conspired to prolong the wait for a new stadium. With the fans turning out in solid numbers at the Metrodome throughout the 2000s, there was no screaming imperative to build a new park.

The Twins, in proper Midwestern fashion, did things their own way. In the wake of Camden Yards’ glorious opening in Baltimore, the path to new ballpark bliss in other municipalities usually began with a team letting its aging facility slip into disrepair. When fans stopped turning out at the decrepit yard, they started spending less on talent and losing games and began floating rumors that they might just have to move away to greener baseball pastures. This prompted taxpayers to approve emergency funding measures to keep their beloved boys of summer in town. All of this played out, of course, during the boom-time late 1990s and early 2000s. The Twins were struggling during these years, but the call to build a new yard fell on deaf ears. So the Twins just skipped all the intermediary steps and with some keen drafting and smart trades, general manager Terry Ryan’s front office rebuilt the team without a new stadium. And Gardenhire and his young players took care of the rest.

Meanwhile, a funding plan for a stadium meandered through the Minnesota state legislature at a pace reminiscent of the glaciers that gouged out the ten thousand odd lakes in the Gopher State some ten centuries ago. Finally, the bankroll for a new yard was approved in 2006. Then, Hennepin County

surmounted several rolls of red tape to acquire by eminent domain a just-big-enough-for-a-park parcel of land in Minneapolis’s Warehouse District, west of downtown. In May 2007, work began to demolish and cart off the buildings on the site, and then in August local luminaries took part in an official groundbreaking ceremony. The Twins contributed about $170 million of the $420 million stadium price. Factoring in the cost of the land, site preparation, necessary infrastructure improvements, and financing, however, the true cost of Target Field checked in at more like $520 million. That’s no small investment in the local nine but still represents much less than it would have cost to build the retractable-roof facility some pundits and fans expected. As it turned out, even without a lid, we think the Twins did just fine. They did fine when it came to negotiating a naming-rights deal too. It’s easy these days for writers like us to dress down teams that give in to the corporate powers that continue to infiltrate our game, but how can you blame the Twins for selling out when the sweetheart deal they signed with Target will yield a reported $125 million between 2010 and 2033?

Kevin:

That’s fine, but I for one won’t be shopping at Target anymore.

Josh:

But you drink Miller, Coors, and Busch and they all have parks named after them.

Kevin:

Only reluctantly do I drink those macros when nothing better’s available.

Josh:

You drank Minute Maid orange juice at breakfast today too.

Kevin:

Juice is another exception.

Josh:

Correct me if I’m wrong, but didn’t you just buy that Pork Chop on a Stick with a Citibank debit card?

Kevin:

Let’s just watch the game.

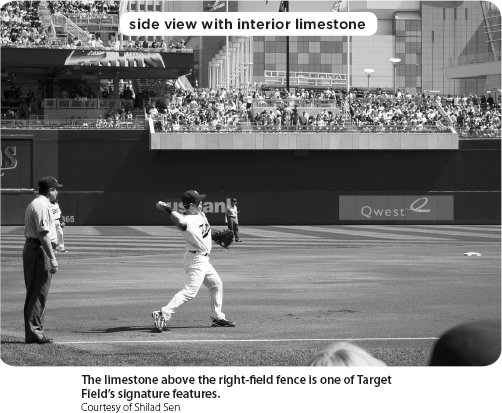

Target Field occupies a smaller than typical stadium plot in a location just a stone’s throw from the Minnesota Timberwolves’ Target Center and a commuter rail station, within a Warehouse District full of restaurants and bars. The park’s most unique design aspect is its generous interior and exterior use of a tan-colored limestone from Minnesota’s Kasota Quarry. This is the same stone that was used in the construction of PNC Park in Pittsburgh, but it’s featured much more prominently at Target, which is a fancy way of saying “slabs of the stuff are everywhere, here.” In fact, the ballpark incorporates more than one hundred thousand square feet of it. From the street outside the smooth lime is complemented by glass panes and plenty of steel. We found the façade, while unique and modern, a bit cold.

Josh:

We just redid our bathroom with these exact tiles.

Kevin:

I wouldn’t say that too loud here.

Inside, the limestone appears behind the plate at field level and on the Club level, on the dugout roofs, in deep foul territory, and atop the right-field fence. It presents a nice contrast to the forest green seats. Here, we liked the effect better. Truly, in the seating bowl and on the field this park shines. The relatively small confines offer room for just a shade over forty thousand spectators, including those holding standing passes, making for a cozy, if slightly cramped, atmosphere that offers good views of the action all the way around the diamond. There are three decks of seats, but none extends too far back or rises too sharply to leave fans feeling removed from the game.

A grove of twelve six-foot-tall black spruce trees originally stood beyond the fence in center to serve as the batter’s eye but the trees were uprooted after the 2010 season because batters complained about the shadows they cast. In their place, the Twins installed a honeycomb-like material that supposedly provides an ideal backdrop for ball-spotting batters. We just hope it doesn’t attract bees! Or bears! The evergreen batter’s eye was actually only a small facet of a larger complaint several Twins hitters voiced during the first season at Target. The main

criticism was that Target—which had been billed as a neutral setting that favored neither hitters nor pitchers—was a pitcher’s paradise. While it’s tempting to say sluggers like Justin Morneau and Joe Mauer were merely spoiled by playing so many games at the “Homer Dome,” the stats do back up their contention. In Target’s first season, the Twins—whose lineup remained practically identical to the year before—saw their long balls in home games dip from ninety-six in 2009 to just fifty-two in 2010. Mauer and Michael Cuddyer especially suffered, as the All-Star catcher hit just nine HRs compared to twenty-eight the year before, and Cuddyer saw his homers drop from thirty-two to fourteen.

Josh:

Some “neutral” park.

Kevin:

Yeah, but those guys both had career years in ’09.

Josh:

I’m just bitter because I had Mauer on my fantasy team.

Instead of spending their money on an overblown frill like the riverboat in Cincinnati, the choo-choo train in Houston, the swimming pool in Arizona, or the fish tank in St. Petersburg, the Twins eschewed what must have been an obvious temptation to add a few lakes or at least a walleye pond inside Target Field and sank their money instead into more practical ballpark accessories. Amidst concern that cold April showers would subject fans to a degree of misery unbefitting paying customers, the Twins saw to it that Target Field include a more-expansive-than-usual sunroof over the upper deck to provide shelter on rainy nights. And realizing that the average nightly low in April in Minneapolis is 36 degrees Fahrenheit, they installed 250 overhead heating units on the main concourse in time for Target’s opening. Then, after the first season, they installed 130 more heaters on the main concourse and terrace. Additionally, they outfitted the upper deck with radiant heating. And from the start, they’ve kindled a bonfire on cold nights out on the left-field party deck. The fire burns in a big rectangular pit around which fans huddle on frigid eves.

Kevin:

You read that right: a freaking bonfire inside the park.

Josh:

You won’t see that anywhere else in the bigs.

Kevin:

Well, there’s an outdoor fireplace at Safeco.

Josh:

That’s not the same thing.

It’s nice of the Twins to go to such lengths to ensure their fans won’t freeze to death, but probably unnecessary. After all, the fans survived for years at heater-less Metropolitan Stadium before the opening of the Dome in 1982. The Twins of Harmon Killebrew, Tony Oliva, and Rod Carew had played at that Bloomington, Minnesota, yard dating back to the franchise’s arrival via Washington in 1961. Prior to the erstwhile Senators’ migration, the minor league Minneapolis Millers had called the “Met” their home since its opening in 1956.

The Metrodome supplanted the old park on April 6, 1982, following the Astrodome and Kingdome to become baseball’s third dome. (We’re not counting Olympic Stadium in Montreal, because it was technically a retractable-roof facility, even though the roof usually refused to cooperate.) Today, the NFL’s Minnesota Vikings still play at the Metrodome, although a movement is afoot to build a new stadium in town too. For the time being, traveling fans can still pay the Dome a visit while in town, though. It is something to see. The ten-acre roof measures just 1/32nd of an inch thick. It is made of Teflon-coated fiberglass and kept aloft by two hundred and fifty thousand cubic feet of air pressure per minute, supplied by electric fans. It was named after Hubert Horatio Humphrey, the thirtieth vice president of the United States. After serving as second in command to Lyndon Johnson,

Humphrey received the Democratic nomination for president in 1968, but lost to Richard Nixon. During his tenure as VP, the liberal champion served as chairman of the National Aeronautics and Space Council, so perhaps Minnesotans thought it fitting that their “space-age” ballpark should bear his name. Or maybe they just wanted to honor a local pol, who after graduating from the University of Minnesota, served as mayor of Minneapolis and then represented Minnesota in the Senate.