Ultimate Baseball Road Trip (36 page)

Read Ultimate Baseball Road Trip Online

Authors: Josh Pahigian,Kevin O’Connell

A well-known fan in the 1970s and early 1980s, Orioles devotee Wild Bill Hagy was a Maryland cab driver, who would hop up on top of the home dugout at Memorial Stadium and treat fans to his trademark “Roar from Thirty-Four,” so-called due to Hagy’s preferred seating location in Section 34. Hagy was also the one who started the tradition of yelling “O” when the National Anthem singer gets to the “Oh, say does that Star-Spangled Banner yet wave” line in the “Star

-

Spangled Banner.” Hagy deserves credit for inspiring a tradition that has lasted long beyond his days, a tradition that even traveled with his favorite team and its fans to their new ballpark.

We Met a Legendary Super-Fan

Talk about a dream job … well, other than ours. After meeting one of his helpers during our water taxi ride earlier in the day, we sought out Jay Buckley in section 74 of Oriole Park’s left-field boxes. Jay is the founder and director of the oldest national baseball tour business in the country,

Jay Buckley’s Baseball Tours.

You’ve probably seen his ad in the newspaper.

Jay, who runs his company out of La Crosse, Wisconsin, told us he began traveling to ballparks in the 1970s during

his vacation time. In 1982, he took his first tour groups on the road, chauffeuring forty-two people around the country. In 2011, more than twelve hundred people joined Jay on his twenty-four bus tours that departed via luxury coach from cities across the country. Jay’s schedule takes him and his traveling band of fans to spring training games in Florida and Arizona each year, too, and to the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

In case you’re wondering, Jay grew up a Milwaukee Braves fan. We tried to pin him down on his favorite team these days, but he wouldn’t play ball. “I’m a fan of the game,” he said. “I hope every division goes down to the final day of the season.”

Some folks in Jay’s position might have seen our book as a threat, but Jay seemed genuinely happy to make our acquaintance. He seemed to agree with our take on the matter: there’s room for an ultimate baseball tour book

and

an ultimate baseball tour guide in the MLB universe. So we offer Jay our whole-hearted endorsement. If your car’s in the shop, if you’re waiting out a ninety-day license revocation, or if driving just isn’t your thing, check out Jay’s itinerary at

www.jaybuckley.com/

.

ATLANTA BRAVES,

ATLANTA BRAVES,TURNER FIELD

The Tomahawk Chopping Grounds

A

TLANTA

, G

EORGIA

465 MILES TO CINCINNATI

480 MILES TO ST. PETERSBURG

555 MILES TO ST. LOUIS

640 MILES TO WASHINGTON

T

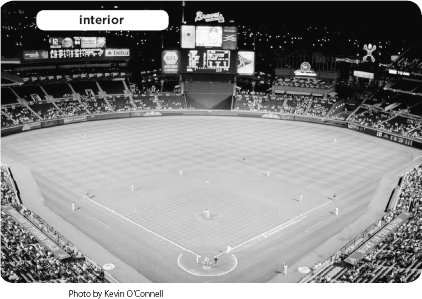

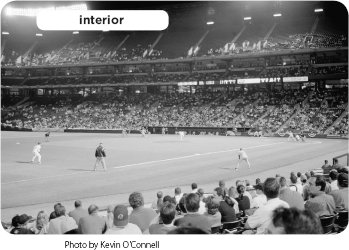

he Braves strive to make Turner Field a game-day setting fans of all ages will find highly stimulating. And the team largely succeeds in this mission. Aside from providing a beautiful lawn for a game, the stadium also functions as something of an entertainment machine. To begin, it comes complete with two massive video boards—one for fans in the seating bowl and one for fans on the ginormous entry plaza/food court. Its nooks and crannies also house more than seven hundred flat-screen TVs throughout the park. But what would you expect in the town where cable pioneer and stadium namesake Ted Turner reinvented television and where the network he founded—CNN—still bases its world headquarters?

More than just catering to tube-heads and technophiles, though, Turner Field also meets the needs of every other stripe of fan. For hardball history buffs, it offers a plaza chock full of statues and monuments, a top-notch franchise Hall of Fame, and a portion of the left-field wall from old Fulton County Stadium, marking the spot over which Hank Aaron’s record-breaking 715th home run sailed. For art aficionados, Turner features baseball sculptures and murals. For armchair managers—or perhaps we should say general managers—Scouts Alley provides vintage player evaluation reports pertaining to some of the Braves most memorable players. For big eaters and dog lovers, Turner more than satisfies. And for kids, Turner provides video games, goofy contests, fuzzy mascots, and a thirty-three-thousand-square-foot fun zone called Tooner Field. Oh, and did we mention there’s a miniature field where fans can test their skills on the upper deck?

Does Turner Field try to do too much? Maybe. All of the peripheral activity can distract from the game a bit. But we enjoyed our stroll through Scouts Alley almost as much as we enjoyed watching the game. And ever since Josh left Atlanta he’s been hankering for another Bison Dog. And Kevin can’t stop talking about the autographs he got at Tooner Field … for his girls, of course, not himself.

As for its not-so-humble beginnings, Turner Field came into existence in the mid-1990s when the Braves joined forces with Atlanta’s Olympic Committee to build a stadium capable of hosting the track-and-field portion of the 1996 Summer Games. From the start, the plan was to build a stadium that could afterwards be remodeled to accommodate baseball. Notice, we said, “remodeled.” Unlike old Olympic Stadium in Montreal, which underwent very few modifications before being handed over to Les Expos after the 1976 Games, “The Ted” underwent a serious reconfiguring. The conversion cost the Braves $35.5 million. Clearly this was money well spent. Turner Field is a superb stadium for baseball.

Just how drastic was the remodeling, you wonder? Well, the huge limestone columns you’ll notice rising on the plaza outside the main entrance once supported seats for the Olympic Games. Back then, the stadium held eighty-five thousand spectators. Now The Ted accommodates only about fifty thousand. Imagine, the expansive entrance plaza that makes the facility so distinctive today was once part of the stadium’s interior. And yet, all of this work was completed between September 1996 and April 1997. That’s a pretty ambitious makeover in our book.

Kevin:

I got a makeover once.

Josh:

Yes, I remember.

Kevin:

It was back when the first edition of

The Ultimate Baseball Road Trip

came out, right before our debut appearance on ESPN’s

Cold Pizza.

Josh:

Yes, our

debut

appearance, and

only

appearance.

Kevin:

I still can’t believe you said “bull testicles” on national TV.

Josh:

Hey, Rocky Mountain Oysters deserved an honest description.

Kevin:

And you sure provided one.

The Braves opened Turner Field, with a 5-4 come-from-behind win against the Cubs on April 4, 1997. Later that year, Atlanta won the first two postseason games at Turner Field,

on the way to a sweep of the Astros in the National League Division Series. The Braves lost in the National League Championship Series, however, to the Marlins, who went on to win the World Series.

As for The Ted’s predecessor, the city imploded multipurpose Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium in 1997. The facility had been the home of the Braves since they moved from Milwaukee to A-Town in 1966. But the stadium wasn’t theirs alone. They shared Fulton with the NFL’s Atlanta Falcons until the “Dirty Birds” finally migrated to the Georgia Dome in 1992.

“The Launching Pad,” as Fulton County Stadium was often called, was the Coors Field of its day thanks to its altitude of more than a thousand feet above sea level, which resulted in a higher-than-usual number of home runs. Today, Turner Field sits not far from the old stadium’s footprint at the very same altitude, but folks don’t make as much fuss about its homer-friendliness in the wake of so many long-ball-friendly yards that have popped up in recent years. And they shouldn’t. From 2001 through 2010 Turner Field only once cracked the top-ten list of parks allowing the most homers per game.

Although it was a multipurpose facility, Fulton County Stadium had some interesting features that distinguished it from the other cookie-cutters. Chief among these were some Native American features that would likely be deemed politically incorrect by today’s standards. For example, when the Braves first arrived, “Big Victor” stood beyond the outfield fence. The totem pole’s eyes would light up whenever a Brave homered. Then in 1967 fans welcomed Chief Noc-A-Homa to the yard. The tepee stood on a platform behind the outfield fence until it was removed in September 1982 as the Braves, expecting to make the playoffs, freed up space for extra seats. When the team began slumping, the Chief was restored to his rightful place and the Braves rediscovered their winning ways en route to claiming the National League West title by a single game over the Dodgers. Yes, you read that right. The geographically confused overseers of the American Game once had Atlanta playing in the Senior Circuit’s

western

division. This madness was fortunately remedied by the realignment of 1994. As for those 1982 Braves, they were swept by the eventual World Champion Cardinals in the NLCS.

Hank Aaron made Atlanta’s 1974 home opener memorable, swatting homer No. 715 against the Dodgers. The shot broke Babe Ruth’s career record and has since become one of those magical baseball moments, right up there with Bobby Thomson’s “Shot Heard ’Round the World” and Kirk Gibson’s limp around the bases. What baseball fan worth his salt wouldn’t recognize the now grainy footage of Aaron circling the bases trailed by those two goofy college kids who jumped out of the seats to accompany him?

After the 1974 season, the Braves traded “Hammering Hank” to Milwaukee, where he finished his career with two mediocre seasons in the city where it began. For the Braves, a prolonged spell of futility continued. Between 1970 and 1990 the team enjoyed just four winning seasons, despite being billed as “America’s Team” for much of that time as TBS beamed their foibles into living rooms across the country. Under Turner’s ownership, the team eventually recovered to post the best winning percentage in the Majors during the 1990s, though. The highlight of this resurgence was a World Series title, clinched at Fulton County Stadium against the Indians in 1995. Atlanta won the sixth and deciding game, 1-0, behind a combined one-hitter by Tom Glavine and Mark Wohlers. Dave Justice accounted for the lone run, with a sixth-inning homer.

The last game ever played at Fulton County Stadium was Game 5 of the 1996 World Series, a 1-0 loss against

Andy Pettitte and the Yankees that left the Braves down three games to one in a Series they would lose two days later. No other park closed its gates for the last time after a World Series contest.

Before moving to Hot-lanta, the Braves had called Brew City’s County Stadium “home” from 1953 to 1965. To learn more about that park, refer to our chapter on Milwaukee. Going back even further, to before the Braves’ stay in the Land of Brats, the team had played at Braves Field in Boston from 1915 to 1952. The franchise’s history in Boston dates back to 1871 when it played as the Boston Red Stockings in the National Association, which became the National League in 1876. By 1889 the team was more commonly called the Beaneaters, and by 1909 the nickname had changed to Braves. Always second to the Red Sox in the hearts of New Englanders, the Braves struggled to draw fans in the 1930s and 1940s. In the Braves’ last season in Boston, only 280,000 fans turned out to see them play. The Red Sox drew 1.12 million that year.

So the Braves moved to Milwaukee after the 1952 season as part of the NL’s first realignment of the Modern Era. Initially, the move was a smashing success. The Braves set an NL attendance record, drawing 1.8 million fans in 1953. Then, in 1957 Lew Burdette blanked the Yankees in Game 7 of the World Series to bring the Braves their first title since 1914. The next year, the Braves fell to the Yankees in another seven-game October Classic. Despite the team’s success on the field, attendance steadily dropped at County Stadium, though, reaching a nadir in 1965 when the Braves attracted just 550,000 fans.

So, off to Atlanta the team headed, where in 1966 more than 1.5 million people visited Fulton County Stadium to see Aaron swat homers and Phil Niekro toss butterflies past batters. The Braves flourished in Atlanta—for a while. But by 1975 they were struggling to draw again. Having dealt Aaron to the Brewers, the Braves attracted just 530,000 fans. Turner bought the team that year and added it to his Turner Broadcasting portfolio. Soon, fans across the country were “treated” to Braves games on TBS. Fast-forward two decades and Turner shrewdly parlayed the team’s revival and Atlanta’s Olympics into a shiny new ballpark for his team. But Turner Broadcasting merged with Time Warner in 2001. And later, the conglomerate merged with AOL. For a while Mr. Turner played a leading role in the new company, but when he resigned his post as AOL Time Warner’s vice chairman in early 2003, his reign as Braves boss officially ended. In 2007 Time Warner sold the Braves to Liberty Media Group, further distancing the team from the family of companies Ted once led.

But despite this, and despite the memories we still have of Turner and his one-time sweetheart Jane Fonda snoozing beside Jimmy Carter in the owner’s box during a playoff game, fans should not forget the impact Ted Turner had on the game. He turned the Braves, perennial losers, into the most dominant team in the National League, and brought a premier ballpark to the city. And he brought about a world of new possibilities in how we enjoy the game on the tube as well.

Nonetheless, it should be noted that Atlanta had a long love affair with baseball before Mr. Turner and even the Braves arrived. The game’s roots in the city run deep, even if Atlanta has only been a Major League city for five decades. From 1901 to 1965 the Atlanta Crackers were the most successful minor league team in the country. The class of the Southern Association spent most of its history competing at the Double-A level and thanks to its success was regarded as the minor leagues’ version of the Yankees. The Crackers won seventeen Southern Association titles in all, playing primarily at Ponce de Leon Park and then Spiller Field, before spending their final season at Fulton County Stadium, as the city awaited the Braves’ arrival.