Ultimate Baseball Road Trip (68 page)

Read Ultimate Baseball Road Trip Online

Authors: Josh Pahigian,Kevin O’Connell

Pops’ Plaza is an area of Willie Stargell–themed stands off the main concourse on the first level. Head for the blue neon near the Rotunda in left field and see if you can guess all the Pops’ references. Pub 475 serves Penn draft and Premium draft as well as pub grub. Familee BBQ is better than Manny’s BBQ in the outfield. Pop’s Potato Patch has freshly cut fries with toppings that include chili, nacho cheese, garlic, chives, and sour cream. Chicken on the Hill has two-, three- or four-piece dinners. Willie’s Hit offers New York kosher style hot dogs, sauerkraut, chili, nachos supreme, and hand-rolled pretzels topped with salt, cinnamon and sugar, or garlic.

As for Manny’s Barbecue, former Pirates catcher Manny Sanguillen operates this barbecue in center field and serves up sandwiches and platters of pit beef and smoked pork. We tried the pork, which was very tasty, healthy on the barbecue sauce but perhaps a bit too salty. It was also pricey for our liking, but good nonetheless.

Rita’s Italian Ice is a cool and sweet treat on a hot day.

Most of the food offerings at PNC are good. In fact, one of their marketing campaigns was “Come Hungry!” We can only assume that people have not been coming merely for the baseball experience for the past two decades. However, there are items to avoid. The pizza is downright dreadful. Follow our “avoid pizza at the ballpark rule” here and thank us later.

Pittsburgh has more than a few of its own breweries that offer beers at PNC. Penn Brewery has a nice selection that includes Penn Lager and Augustiner, a dark bock-style beer. The brewery is on the North Side and is worth a visit. But for the old-time Pittsburgh beer drinkers, Yuengling is still what it’s all about. This very tasty beer originates from the oldest brewery in America, dating from 1872. Iron City is yet another macro-brewery for which the Burgh is famous. Try an IC Light if you’re counting calories.

The same limestone and yellow bricks used on the exterior of the park also line the openings of the tunnels leading to the seats and are visible along the low wall behind home plate. This ties the entire park together in a unified theme. But behind home plate it can actually affect play. If a wild pitch gets past the catcher, the uneven angles of the limestone can send the ball in crazy directions and lead to extra bases, or even runs. Here’s hoping the hometown Bucs figure out these nuances and play them to their advantage … or file the edges off their fancy rocks.

Since PNC opened, scores of pregame pubs and restaurants have opened near the ballpark. One might think this would signal the death knell of the more traditional tailgating that Pittsburghers have perfected on cold fall football days in support of their gridiron glories. Not so. Tailgates are alive and well in the Burgh, regardless of the sport or weather forecast. So why not break out the Hibachi, crack open a 40, pull up on a stretch of concrete, and enjoy the good life wandering among parking lots full of friends who are doing the same? There aren’t many cities that can do it as well as Pittsburgh. Plus, it’s within the road trip budget.

Practically every ballpark has some kind of racing entertainment during one of the breaks between innings these days. We’re not sure why. In Pittsburgh it’s a pierogie race. Jalapeño Hanna, Cheese Chester, Sauerkraut Saul, and the highly sarcastic Oliver Onion are the pierogies in the

running. First they compete on the scoreboard, then they finish as actual characters racing out onto the field. By the way, in a competition between the pierogies of “The Burgh” and the sausages of Milwaukee, the pierogies won out. See the Milwaukee chapter for more details on “Sausage Gate.”

Watch for hot dogs being fired out of an air-gun by the Pirate Parrot. The Pirate Parrot is the team’s mascot and is usually patrolling the park between innings, offering promotions that you might find in a minor league park. During play, look for him to roost atop the Pirates dugout.

The Left Field Loonies sit in Bleacher Reserved seats (Sections 133–138) and are easily the greatest super-fans still attending games at PNC. The short porch in left (325 feet) and the low wall just six feet above the field allow the Loonies to get into the ears of the opposing left fielder. Check out their website at

www.leftfieldloonies.com

and maybe they’ll invite you to one of their tailgates. Trust us, it’s worth it.

Cyber Super-Fans

- Pittsburgh Sports

- Bucs Dugout

- Rum Bunter

- Pirates Home Plate

Kenny “The Lemonade Man” Geidel passed away in May of 2011, and the city lost one of its greatest super-fans. For decades Geidel could be heard at Pirates, Penguins, and Steelers games shouting “Limon-aaaaaaade” in his distinctive squealing style. He also sold cotton candy and soft drinks. This town will likely not see another vendor who worked harder, had more charm, and embodied the teams he loved. Rest in peace, Kenny.

Back in the 1930s, Bruce “Screech Owl” McAllister rose to prominence at Forbes Field as the most famous Pirates rooter yet. His screech, which some compared to the sound a train-whistle made, prompted Pirates management to bribe him to put a sock in it with the promise of free season-tickets for life. He took the deal, but continued to screech, just not as frequently, and only at key moments in the game.

The Local Bushers

The Altoona Curve, Erie Seawolves, and Buffalo Bison are minor league teams that won’t take you too far out of your way. But also check out the Washington Wildthings who have introduced perhaps the funniest minor league team name since the Toledo Mudhens. An independent member of the Frontier League, the Wildthings just opened a new park, Falconi Field, twenty minutes away, in the town of Washington, Pennsylvania.

We Got Lost … Very Lost

As we’ve already mentioned, if you don’t know where you’re headed in this city of bridges and tunnels, you can get really lost, really quickly. Here’s a story from our first baseball road trip that was too good not to retell.

After an enjoyable game at PNC where we witnessed a Pirates loss, we walked back across the Clemente Bridge to the car. We had an early game the next day in Cincinnati and needed to get a head start. We were on the right road for a while, but something happened. Something bad. Yeah, we got lost. Josh attributed it to Kevin not paying attention to his driving. Kevin blamed Josh for being a bad navigator. Josh blamed the stereo, which had been “acting up” and distracting him. It turned out, it was just one of Kevin’s many Bob Dylan CDs and it was working fine. But before we knew it, we were in a town called Beaver, Pennsylvania. We’re not making this up.

Finally Josh realized he had the map upside down and set us on a course along the Ohio River in search of Interstate 70 South. What we found were the remaining steel mills, coalmines, and nuclear facilities that once made this region famous. At night, however, it was eerie as hell, the steam glowing orange from the fires in the kilns.

To make matters worse, Kevin had let the gas gauge drop down near empty and we were going to have to stop in one of these little towns for petrol.

“How could you let it get down so low?” Josh cried, doubtlessly envisioning his demise.

“I thought we’d get gas off the Interstate,” huffed Kevin. “How was I to know you’d lose the entire freeway.”

“I didn’t lose the freeway!”

“Well, the freeway certainly didn’t lose us!”

In any case, neither of us was looking forward to stopping for gas in one of these little shanty work towns, at night, and in a fancy rental car (we always travel in style) with out-of-state plates.

Eventually the main highway turned into a minor highway, and then into a country road. Then a funny thing happened somewhere south of East Liverpool. The road we were traveling on, that once was a highway, ended. It turned into a dirt road, then made a hard right turn. Then it was gone.

“What happened to the highway?” asked Kevin.

“I dunno,” said Josh.

We slowed the car to see rickety wooden houses with dark shadowy figures sitting on the porches. Just then Kevin starting humming “Dueling Banjos” from the film

Deliverance.

“Ba-da-da, dee-da-da-dee-dee-da.”

“Cut that out!”

“Sorry,” said Kevin. “Ba-da-da De-da.”

“Stop!” cried Josh. Kevin laughed, but realized he was getting scared too.

And along this road we traveled, the porch sitters watching our every move. Then the dirt road made a hard left, and the car lunged, and the road was suddenly paved once again. A little town with an old gas station that still had its lights on became visible and we pulled in and got gas from a very normal-looking man with a very normal pattern of speech and a fair number of teeth.

About twenty miles down the road, however, as we recounted the details of our adventure, laughing and joking, Kevin was pulled over for speeding and was issued a ticket, which made Josh bust out laughing, until he remembered that we had previously agreed to split the cost of any moving violations.

CLEVELAND INDIANS,

CLEVELAND INDIANS,PROGRESSIVE FIELD

A Gateway Yard in the Forest City

C

LEVELAND

, O

HIO

132 MILES TO PITTSBURGH

170 MILES TO DETROIT

248 MILES TO CINCINNATI

290 MILES TO TORONTO

E

very fan worth his or her proverbial salt has seen the 1989 baseball film

Major League,

in which a failing Indians team in a failing ballpark in a failing city decides to shock the world and make a run at the pennant. The movie ends with those fictional Indians beating the dreaded Yankees in a one-game playoff to decide the AL East. What happens beyond that is anyone’s guess. The future, as they say, is yet to be written.

In an instance of life imitating art, the real life Cleveland Indians moved into a new ballpark in 1994 and seemingly enjoyed the type of overnight success portrayed in the movie. The new park accomplished what every big league town hopes a new yard will do. It breathed fresh life and energy into the local nine, the fan base, and the city streets, to the tune of six playoff appearances between 1995 and 2001, 455 straight sellouts, and a thriving Gateway District restaurant and entertainment district.

The Indians staked their claim as one of the best teams of the 1990s and their ballpark became one of the best attended. Cleveland appeared likely to remain an AL force for a good long time. What moviegoers didn’t learn until the second

Major League

movie, however, also came to pass in Cleveland. The fictional Indians team from the first movie didn’t win it all. In the second movie we learn that the Tribe of Willie Mays Hayes and Ricky Vaughn, fresh off their defeat of the Yanks, promptly lost to the White Sox in the ALCS. Sure, they made a good run at baseball’s ultimate prize, but in the end they fell short, just like the real Indians who came close, but were defeated in both the 1995 and 1997 World Series. We have to think that if there were a

Major League V,

set two decades after the magical run that reinvigorated the franchise, the silver screen would show the team floundering once again, before a discouraged fan base.

It seems hard to believe now that once upon a time, “Jacobs Field,” as Cleveland’s jewel of a park was originally known, was a lock to draw forty thousand fans per night and ranked at or near the top of the MLB attendance ledger. And the Indians finished each season at or near the top of the AL Central. But by 2010 the Indians’ since-renamed ballpark sat more than half empty as the team stagnated in the AL’s lower division. Even when the 2011 Indians stood in first place heading into the All-Star break, they did so having played the first half of their home slate before barely twenty thousand fans per game at Progressive Field. But even that was an improvement after they played two April games that season before announced crowds of 8,726 and 9,853 fans. Commentators and pundits thought those crowds actually numbered more like three thousand. In any event, they were the two smallest crowds in ballpark history and they weren’t good signs. We’re not sure if this ennui—which has been symptomatic of the Indians’ fan base since the team’s last title in 1948—is a product of not winning the “big one,” or if the bad economy hit Cleveland’s working class fans harder than the rooters in other cities, or if it’s LeBron’s fault. But we do know that the Indians veered off the template that’s supposed to read: New Ballpark + Good Young Players = Success. And teams that build new yards in the future would be wise to study the situation in Cleveland and to learn from it. What happens once the novelty of a new park wears off? What happens if the home team has two or three ninety loss seasons in a row? What happens when the first wave of trendy new bars and restaurants to open around the park starts to disappear? Do things go back to the way they were before, or can a franchise regain its footing without sinking to the depths it once inhabited? We can’t answer these questions. The future is yet to be written. But Cleveland, better than

any other city that built a park during the retro renaissance, enjoyed instant success, and then fell on hard times, is the place where the first glimpse of an answer will be penned.

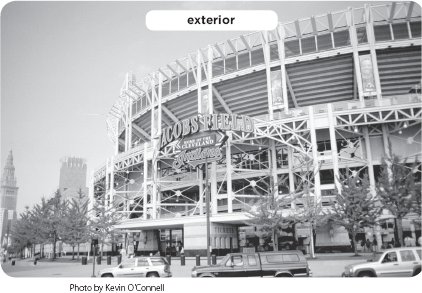

We’re hoping the Indians return to their former glory sooner rather than later. When they do, no doubt Progressive Field will play a leading role. It’s a great ballpark. Though it seats more than forty-three thousand people, most areas of the park feel quite intimate, with only a few sections being too far from the action for our taste. The field is eighteen feet below street level, which helps give the exterior more the look of a ballpark, rather than a towering stadium. From street level, the ballpark only rises 120 feet in the air, not including the light towers.

“The Prog,” as it is often called, was designed with grandeur in mind, as well as baseball. Therefore, it is unashamedly larger than some of the other retro parks such as the ones in Pittsburgh and Miami. The Prog’s exterior reflects the look of Cleveland itself, with light towers reminiscent of the town’s smokestacks, and steel girders that recall the many bridges that cross the Cuyahoga River. The ballpark’s pale yellow brick combines with the exposed steel to invoke the visage of classic ballparks past, as well as postindustrial stadiums.

Asymmetrical field dimensions are always nice, but since most all of the retro parks include them, what we really like to see in a field is distinctiveness, and Progressive Field is brimming with local flavor. Rising above the left-field scoreboard is the city of Cleveland, a wonderful backdrop that ensconces the yard in Clevelandness from the left-field corner to the home bullpen in right-center. Few cities can boast this kind of skyline view and it’s a definite improvement over the backdrop at the team’s old digs. A bit closer to the field than the Terminal Tower and other looming edifices, the “mini monster” in left field provides an added dimension for pitchers, hitters, and especially outfielders to consider. This nineteen-foot-high home run wall used to feature a manual scoreboard but now houses a lengthy LED board. The times they are a-changing even in places where retro-funk is celebrated.

Looking at the beauty of the field and skyline, it’s hard to believe the original ballpark proposal called for a dome. Voters turned down a ballot measure that would have raised their property taxes to fund the ill-conceived notion. In turn, team owner Richard E. Jacobs turned to HOK for some open-air blueprints. The sticker price checked in at $175 million, which seems like a steal compared to subsequent ballparks that would open. Jacobs himself claimed naming rights—for a time—by funding 52 percent of the new park’s construction. The remainder was publicly funded through a so-called “sin tax,” a fifteen-year increase in alcohol and tobacco sales tax in Cuyahoga County. Hey, we can understand taxing smokers—but why alcohol? No fair, especially when doctors say drinking a beer or two a day promotes good health. But anyway, at least it’s a voluntary tax—for most people. The Indians also presold all of the park’s luxury boxes, and sold tax-exempt bonds to cover the remaining costs.

Previously, the Indians played at Municipal Stadium, an enormous structure that seated more than seventy thousand people. The ballpark felt empty and cavernous, even when a respectable crowd of, say, thirty thousand turned out. Municipal Stadium was meant to be the Yankee Stadium of Cleveland, built with high hopes that crowds would fill the place. In our baseball journeys we have found other cities like Toronto that have pejoratively nicknamed their stadiums the “Mistake by the Lake,” but clearly the one in Cleveland, which was exposed to the brutal winds off Lake Erie, was the originator of this infamous moniker.

There are conflicting reports about why Cleveland built Municipal in the first place. Known as “Lakefront Stadium” when it opened in 1931, the park, some say, was

built in an effort to draw the 1932 Olympics to town. That theory would further the “Mistake by the Lake” mythos, but we found the claim to be unsubstantiated. As far as we can tell Los Angeles had already been chosen to host the 1932 Games when ground was broken on Cleveland’s super-stadium. Lakefront—a cookie-cutter prototype—was built to house baseball, football, and other functions under one roof, or in this case, beside one chilly lake. Optimistically, the city thought it might draw eighty thousand people to a baseball game, and publicly funded the $2.5 million monstrosity—making Cleveland’s the first publicly funded big league stadium ever built, and during the Great Depression no less.

Municipal was declared ready for play on July 1, 1931. But the Indians had yet to agree with the city on the terms of a lease, so their first game at the park didn’t occur until July 31, 1932. We’re thinking this probably wasn’t the grand debut the city had imagined. Once the Tribe took roost though, they made the park their home for the remainder of the 1932 season and for the 1933 season. But the ballpark was frequently deserted, and so, beginning in 1934, the Indians played there only on Sundays and holidays when larger crowds than usual were expected. The high cost of operating the huge facility made it preferable for the Indians to play most of their games at League Park, their former and much more intimate home.

League Park, the first home of the Indians, sat on the corner of 66th and Lexington, in the heart of what was once Cleveland’s most prosperous area. Though the team underwent several name changes, Cleveland was one of the original members of the American League when it was founded in 1901. The “Cleveland Blues,” as they were first known, became the “Broncos,” then the “Naps” in honor of star player Napoleon Lajoie. The Indians moniker gained popularity when Louis “Chief” Sockalexis, the first Native American known to play professional baseball, rose to fame in Cleveland. Sockalexis had great talent but his years in Cleveland (1897–1899) were marred by personal problems, and his performance slipped dramatically after a promising rookie campaign in which he batted .341. Before his Major League career Sockalexis played for the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, Josh’s alma mater.

On October 2, 1908, Cleveland’s Addie Joss tossed a perfect game against Chicago. Tragically Joss would die three years later of spinal meningitis. A benefit game for the Joss family was held at League Park in 1911, featuring many of the greatest players of the day, including Ty Cobb, Walter Johnson, Tris Speaker, Cy Young, and Lajoie. The game, which raised nearly $13,000, would be a forerunner of today’s All-Star Game.

Baseball had a convoluted history in Cleveland even before League Park. The city played host to a National Association team called Forest City in 1871 and 1872. From 1876 until 1884, Cleveland placed an entrant in the National League, and in 1886 and 1887 a Cleveland team played in the American Association. The year 1890 saw two Cleveland outfits in action, one in the NL and one in the ill-fated Player’s League.

On May 1, 1891, the Cleveland Spiders, led by the great Young, played their first game at League Park. Though the Spiders never led the NL in wins, the “arachnids” did find their way to the Temple Cup, the equivalent of today’s World Series, three times—in 1892, 1895, and 1896, winning the 1895 series with a victory over Baltimore. But the team made the record book in another way in 1899 when owner Frank Robinson transferred all of its best players to the St. Louis Browns, which he also owned. After the departure of players like Young, Jesse Burkett, and first baseman/manager Patsy Tebeau, the Spiders posted an all-time-worst 20-134 record, finishing eighty-four games behind first-place Brooklyn. After the season, the Spiders were eliminated, as the NL shrunk from twelve to eight teams. There are now rules against owners holding controlling interest in more than one Major League team at a time.

Kevin:

The Yankees might as well own half the teams in the league.

Josh:

Yeah, they wind up with all the best players.

Kevin:

Well not all of them. Your Red Sox take the other half.

League Park had an odd square-shaped field, with its deepest corner just left of center field stretching to 505 feet from home plate. The right-field corner, meanwhile, was a very shallow 290 feet from the plate, so a forty-foot-high wall was constructed. Atop the wall rose twenty feet of chicken wire that kept balls in play. A sixty-foot wall? Now that’s what we call distinctive. Why such weird field dimensions, you wonder? Well, prior to the park’s construction, the owners of surrounding properties had refused to sell their land and buildings to the city.