Ultimate Baseball Road Trip (85 page)

Read Ultimate Baseball Road Trip Online

Authors: Josh Pahigian,Kevin O’Connell

The K&J Guide to Fan Etiquette

After spending good portions of this book telling players, owners, and management what they can do to make the game better for fans, we thought this would be a good opportunity to list what fans need to do to keep baseball from turning into something ugly.

- Do not go on the field for any reason. Sure, it was funny back in the day when some lunatic would run around on the field at Yankee Stadium, eluding inept security for as long as possible. But those days are now officially over. If you go on the field now, not only are you risking your own neck, but also those of everyone involved.

- Do not interfere with a batted ball. If you reach down out of your first-row outfield seat to scoop a rolling ball off the ground, you run the risk of depriving the entire crowd of seeing the batter go for a triple. If the catcher throws aside his mask and runs toward the front row of seats to catch a foul pop-up, get out of his way. If you reach out your hand to snatch it before he does, chances are you’ll only deflect it, and it will wind up hitting you, the player, or another fan in the face. Remember what happened on the North Side during the Cubs’ 2003 playoff run.

- After getting treats or using the can, wait until there is a break in the action before you move through the aisle to your seat. People seated on the aisle have to deal not only with you, but hundreds of other people in your section streaming past them, and it’s rude. With all the standing room at these new ballparks, watch the action from the top of the concourse and wait until an out is made, then head to your seat. You’ll thank others for their courtesy when you have seats on the aisle.

- For folks with seats behind the plate: STOP WAVING and stay off of your cell phones. The “miracle” of television has been with us for years now, so don’t distract the pitcher, or the fans seated near you, or the home-viewing audience, by acting like a fool. If you want to wave to the camera and act like a baboon, go stand outside

The Today Show. - Do not, after drinking ten or twelve beers, get it into your head that you’re going to start the Wave. While you’re running back and forth on the concourse yelling “one … two … three … wave!” everyone else is trying to see around you and wishing you’d drop dead, because—get this—they’re trying to watch the game. Besides, the Wave is for football.

- When you see a player outside the ballpark, be respectful. Don’t do rude things, like interrupt a player while he’s eating dinner and grovel for an autograph or snap a picture with your phone. How would you feel if people were always bugging you while your mouth was half full of linguine? Bugging players at inappropriate times does nothing but widen the gap between them and us. If you really want an autograph that badly, wait until the player is done eating, then ask nicely. Who knows, he might even take a picture with you. Or better yet, send him a thoughtful, handwritten letter addressed to his team’s ballpark.

The Sox seem to have arrived at a place of perfect symmetry between the product they are putting on the field, and how their fan base completely represents who they are. There are plenty of Sox fans that used to watch the games only at home, perhaps because they lived in the suburbs or couldn’t afford a ticket. But in U.S. Cellular Field, with all its many and continued improvements, the White Sox have created a compelling place that their fans truly want to visit, and one that they can afford.

Though no longer with the organization, it’s worth remembering Nancy Faust, who was the White Sox organist beginning in the early 1970s until her retirement in 2010. Nancy was a hip tickler of the ivories who was very clever about what she played. She was credited with playing songs that were copied across the nation and have become required stadium anthems. One such tune was when she played “Kiss Him Goodbye” when an opposing pitcher gave up a home run to the Sox. We can’t imagine a world without Nancy Faust, and she will be missed at the ballpark, and in the hearts of Sox fans, and baseball fans everywhere. The good news is, the White Sox have hired a new organist in the wake of Nancy’s departure. So keep an ear out for the melodies of keyboardist Lori Moreland when you’re at The Cell.

Though never an employee of the White Sox, Andy the Clown went to games at old Comiskey for years dressed in full funny man regalia and brought people joy, we think. You see we’re not sure because when the new park opened Andy wasn’t invited to return. Perhaps some traditions ought to “go gently into the good night.” But we thought we’d mention Andy for his many efforts.

We learned a lot about Sox history during our visit, and this seems as good a place as any to talk some more history, as the Pale Hose have history coming out their ears. The rivalry is still fierce between the North Side Nine and the South Side Hit Men. At one time back in the 1990s a billboard above the L train outside Wrigley Field portrayed “the Big Hurt” pointing his formidable bat back toward U.S. Cellular Field. It read “Real Baseball, only 7 miles back.”

But our pal and tour guide Douglas Hammer takes issue with the false notion that because the Cubs routinely sell out their games, they have more loyal fans than the Sox. According to Hammer, team loyalty is split fifty-fifty in Chicago, and the attendance disparity is more due to tourists and college kids looking for a good time in the Wrigley bleachers.

The South Side was once populated heavily with Irish and African-American residents, who jointly supported the Sox. But when many of the Irish left for the suburbs during the so-called “white flight” of the 1970s, Sox support suffered, resulting in a situation that saw many people in the fan base choose to stay at home to watch the team on TV. Now we are left with two notions that further divide the baseball fans of Chi—that Sox fans are urban blacks and Cubs fans are white, yuppie, Big-Ten fraternity punks. Neither of these stereotypes is true.

Cyber Super-Fans

Check out these bloggers and message board moguls who have dedicated their lives to Sox fame and glory over the Internet.

- South Side Sox

- White Sox Interactive

- White Sox Mix

- White Sox Locker

An office building at 54 West Hubbard St. was at one time the Chicago Criminal Courts Building where the infamous Chicago eight were found not guilty of all charges by a jury. A plaque outside marks the court’s role in the Black Sox Trial, as well as other famous trials in the history of Chicago.

Sports in the City

Monsters of the Midway

The South Side is a short distance by car from the Midway. What’s the Midway you ask? Ever heard the term “Monsters of the Midway” used to describe the Chicago Bears? Sure, you have. Well, though it’s only a field, check out the Midway where the World’s Fair was once held and where those Bears were once mighty and victorious and may one day be again.

We Passed a Crucial Test as Travel Partners, Sort Of

Chicago is the kind of a city where you want to be shown around by someone familiar with the turf. We went to the game in a large group of Kevin’s friends that included Jim, Hammer, Paul and Rebecca, Trisha, and of course the two of us. We were earlier treated to a tour of the city by Paul Schmitz and Rebecca Murphy, two of Chi-town’s most avid enthusiasts. We did as much as we could that day. We rode the “L” loop through town, checking out Cabrini Green and Old Town. We saw the great modern architecture of the Monadnock Building, the Rookery Building, and Marshall Field’s department store (now a Macy’s). We went to Navy Pier and saw the fountain that appeared during the opening credits of

Married with Children.

We saw public sculptures and art by the likes of Chagall and Picasso. We walked past the Tribune Building, the original Playboy Mansion—oh la la—and Oprah’s Harpo Studios. We saw the Magnificent Mile and Lincoln Park. We felt a bit like Cameron in

Ferris Bueller’s Day Off.

But when the game ended, Josh called his friends Kristen and Kevin on the North Side of the city to see what they were doing that night. Kevin’s friends Hammer and Rebecca suggested going to Harold’s Chicken Shack, and then out to the Checkerboard Lounge for drinks and blues. Everyone agreed that it would be a great idea.

Josh wasn’t keen on going to a blues bar, plus his friends had whet his appetite with tales of the famous Chicago stuffed pizza near their house in Wrigleyville. And when Josh gets a hankerin’ there’s nothing in the known universe that can hold him back from his quest. So after the game the lingering group stood in a standoff outside the ballpark.

“You already had pizza twice today,” reasoned Kevin.

“So what?” Josh said. “I can’t have pizza three times in the same day?”

“Sure you can, but everyone here wants to stay on the South Side,” said Kevin.

“Yeah, you and Moby,” Josh said. “I’m heading North with my friends.”

“South Side!” Kevin shouted.

“North Side!” Josh shouted back.

“South Side!” Kevin screamed. Clearly, we had reached an impasse.

“Yeah,” said Josh, “Well the White Sox stink. I hate the South Side.”

“And the North Side is full of yuppies,” Kevin replied.

“North Side!” shouted Josh again.

“Why are you being so stubborn?” Kevin asked.

“Why did you root for the White Sox, over my Red Sox?” said Josh.

“I always root for the home team,” shouted Kevin.

“I rooted for the Mariners when we were in Seattle,” yelled Josh.

“South Side!” Kevin yelled back.

Things had been tense between us many times on the road, but never quite like this. Neither of us would budge an inch.

“Will you listen to yourselves?” Kevin’s diplomatic friend Paul said. “You sound like you’ve lived in Chicago your entire lives.”

We’re not sure if it was the city of Chicago that had gotten into our blood so quickly, or if we had simply spent too much time on the road together. And while an amicable solution might have been reached together, we decided that Josh should go out on the North Side with his friends, and Kevin should stay on the South Side with his. We both went our separate ways and spent some much needed time apart. The next day it was as if nothing had happened. We went to the game together on the North Side, and out together afterwards (starting in the South Side and finishing in the North Side) as close as ever. Perhaps during every road trip there should be some time built in for doing your own thing. We recommend it.

MILWAUKEE BREWERS,

MILWAUKEE BREWERS,MILLER PARK

A Brew City Flip-Top

M

ILWAUKEE

, W

ISCONSIN

90 MILES TO CHICAGO

340 MILES TO MINNEAPOLIS

375 TO DETROIT

380 MILES TO ST. LOUIS

S

ince migrating from Seattle to Milwaukee in 1970 and changing their label from “Pilots” to “Brewers,” the team that Bud Selig built has enjoyed some memorable seasons and has presented fans with many talented players to cheer. But through the years the Milwaukee nine has also asked a lot of their fans in the way of patience. The Brew Crew has asked Milwaukeeans to endure seemingly one prolonged rebuilding phase after another. And for the most part, the beer- and brat-loving locals have patiently hung in there, waiting for the day when the Brewers would win their first world championship. It hasn’t always been easy, though, considering that prior to their division-winning 2011 season the Brewers had enjoyed only eleven winning campaigns over the previous four decades.

For years, of course, the Brew Crew’s fortunes rose and fell at County Stadium, which despite its colorful history was not really up to big league snuff by the end of its baseball life. But the fans hung on. Additionally, the Brewers asked their fans to accept the awkward ascent of team owner Bud Selig to the commissioner’s chair, even as he continued to maintain his involvement with the Brewers. And then the Brewers switched from the American League to National League, asking fans to disregard two-generation-old rivalries. These indignities, combined with all of the losing, might sound like a recipe for fan disengagement and franchise implosion. And yet, the loyal fans rolled with the proverbial punches and kept providing steady support of the local nine, making Brew City not just “viable” for big league ball in the twenty-first century but a candidate for a shiny new ballpark. And in 2001 that gleaming new yard became a reality. After some initial fits and starts, during which the team suffered through some lean years after Miller Park’s opening, baseball in the land of brats has flourished. The Brewers closed out the first decade of the 2000s by perennially finishing among the top third of teams in attendance, attracting upwards of three million fans per season. Not bad for the smallest city (by population) in MLB. Just how “small market” is Milwaukee? It has a metro population of 1.5 million. At the other end of the spectrum, the Mets and Yankees draw from a city of nineteen million. Even teams in the middle of the population pack, like the Tigers and Diamondbacks, draw from metros of 4.4 million people.

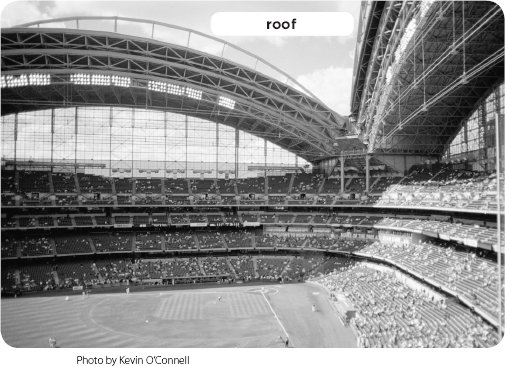

And that brings us back to Miller Park, a post-modern facility, huge in almost every way, which boasts a space-age roof that opens and closes in a fanlike motion and takes just ten minutes to do so. The roof dominates both the interior and exterior of the park. To Kevin, it looks like the gills of a huge space fish. To Josh, who lacks quite the same imagination but likes to make up new terms, it merely looks “techno-classy.” It weighs twelve thousand tons, covers 10.5 acres, and is capable of withstanding twelve feet of snow, or roughly 170 pounds of powder per square foot. When it’s open the park has a remarkable open-air feel. When it’s closed, the building can be warmed 30 degrees Fahrenheit above the temperature outside.

We like this roof a lot. But it does have one dark side that we’d be remiss not to mention. When fully opened and stacked in foul territory the roof’s orientation allows for a large swatch of sunshine to soak the infield during afternoon games. This effect also creates some very dark shadows, though, which has prompted more than a few hitters to complain after 0-for-4 performances. Some fielders have claimed that the dual lighting has made it hard to follow the flight of fly balls too. In 2010 the Brewers began partially closing the roof during day games so that two panels hover over left field and three over right to create a more consistent shadow over the entire infield. That way the pitcher and batter are in the same light environment. But the sun is kept out, and the park doesn’t feel as open to the outside world.

We said earlier that this felt like a big stadium to us. And that’s because it is rather big. The park rises 330 feet, making it roughly three times the height of old County Stadium. But despite this magnitude parts of the park feel very open to the outside world, thanks to the gigantic windows spanning the outfield. These appear on either side of the hitter’s backdrop and video board in center field and continue almost all the way to foul territory on either side of the outfield. Additionally, there are massive arched windows between the top of the upper deck and the roof along the foul lines. These colossal windows are actually composed of many smaller panes of glass all framed together. In total, they allow for light to enter the stadium, even when the roof is closed, for the grass to grow, and for that open-air feel we really appreciate.

Kevin:

I pity the guy who has to squeegee all that glass once a month.

Josh:

Yeah, you have that fear of heights thing.

Kevin:

I was speaking from a housekeeping point of view.

Josh:

I guess that means Meghan cleans the windows back home?

Kevin:

No, they flip around from the inside.

Josh:

Well, la de da, Mr. Fancy Glass.

Outside, the red brick facade is nearly the only nod to the classical ball era. Clearly, the designers at HKS were going for a grand stadium design, rather than an intimate old-time one. Intimate is not ever going to be a word used to describe this place. Not with its abundance of escalators and elevators, its four seating levels, and its multiple underhangs obstructing views. The upper deck seats are pretty poor, but the folks in the lower two decks are treated to a pleasant enough experience.

Upon our first entering Miller, with brats in hand, we found the field as beautiful as it seemed spacious. It sure felt like a ballpark, not a quasi-dome. If you try to measure a second-generation retractable roof job like this to an earlier generation facility like Rogers Centre, you’re not even comparing apples and oranges. More like apples and pineapples. They might sound similar. But the aesthetics of the two are really nothing like one another. And here’s something you won’t find in Toronto, or at any other retractable roof field that we know of: a drainage system beneath the immaculately groomed Kentucky bluegrass that can handle twenty-five inches of rain an hour just in case the roof ever malfunctions.

Josh:

Twenty-five inches per hour? That sounds like Noah’s Ark territory.

Kevin:

If a tsunami ever rips across the East Coast, sweeps over the Lakes and cascades across Milwaukee, the safest place in the city will be the pitcher’s mound.

More than just looking ultra-super-modern from the outside, with its glass “bug eyes,” Miller Park has tried to include many of the features that have become staples of the modern ballpark experience. The concourses are nice and wide, there are patios, restaurants and luxury seats aplenty, and the place is kept nice and clean. But of all the new parks we’ve visited only U.S. Cellular Field does a poorer job at maintaining an intimate feel in the upper reaches. When we were in the lower two decks, we felt involved in the game and sufficiently ensconced in the sort of baseball atmosphere we like. But up in the fourth deck, we felt like we were in a whole different baseball stadium.

Kevin:

Hmm. I can’t believe people willingly pay to sit up here.

Josh:

Now I understand why Bob Uecker is a Milwaukee icon.

Kevin:

Did the second baseman just miss the tag?

Josh:

I’m pretty sure they’re still just throwing the ball around the infield.

Kevin:

You mean the inning hasn’t started yet?

Miller’s journey into being was arduous. When attendance was dropping and the team struggling, funding for the project was slow in coming and then just barely secured. It took State Senator George Petak changing his vote on a proposed funding package late at night on the third ballot to officially set the stadium ball in motion in 1995. Shortly thereafter, the Republican lawmaker was recalled from office. But eventually Wisconsin Governor Tommy Thompson signed the Stadium Bill into law at a ceremony in the County Stadium parking lot. The law guaranteed taxpayer funding of the new park and stipulated that the Brewers would stick around for at least thirty years.

There were still hurdles to clear though as the funding plan had to be restructured when it became apparent the Brewers didn’t have the collateral to insure a loan. When all that got sorted out, controlling interest in Miller Park belonged to the State Stadium Board because the taxpayers of five Wisconsin counties had paid $310 million of the $400 million price. How did they pay this, you ask? With a 0.1 percent sales-tax hike that raises about $20 million a year. The Brewers, meanwhile, own 23 percent of the park, having chipped in $90 million. Miller Brewing Company paid $40 million for the naming rights, which run through 2020.

The construction contractors broke ground on the project in November of 1996 and it took a longer-than-usual five years to build the stadium. The outfield dimensions were designed with help from Brewers Hall of Famer Robin Yount and former general manager Sal Bando. Yount’s intention in deepening the outfield wall between the power alleys was to increase the frequency of what he considers the most exciting play in baseball: the triple.

The building of Miller was fraught with peril. Three construction workers were killed in July of 1999 when a 567-foot-high crane collapsed while lifting a four-hundred-ton roof panel that bent in half and crashed to the ground. The accident also caused $100 million in damages to the construction site. Some blamed the deaths of Jerome Starr, Jeff Wischer and William DeGrave on high winds at the time of this delicate construction procedure and questioned whether the rush to finish the stadium had prompted unwise decisions at the work site. Mitsubishi, which was contracted to construct the $47 million roof and oversee the project, faced penalties if the stadium was not ready in time for Opening Day 2000 and some pointed to it in the rush to apportion blame. In the aftermath of the horrific accident, a court ruling found Mitsubishi 97 percent negligent and another company 3 percent negligent and awarded $99,250,000 in damages. Ultimately the case wound up being appealed to the Wisconsin Supreme Court, which in 2005 upheld that decision.

The final game at County Stadium took place on September 28, 2000, and was attended by Yount, Hank Aaron, Rollie Fingers, Warren Spahn, and other Milwaukee luminaries. Finally, the next spring, the day Milwaukeeans had been waiting for arrived. On April 6, 2001, the Brewers defeated the Reds 5-4 on an eighth-inning blast by Richie Sexson in Miller Park’s inaugural game.

During that first year, the Brewers drew more than 2.8 million fans to their new digs, setting a new franchise record. In 2002 Miller Park played host to the All-Star Game, a moment in baseball history that will forever be tarnished because it disappointingly ended in a tie when Selig declared the game finished rather than let it continue past the tenth inning. In 2008, the Brewers passed the three million mark in attendance for the first time, averaging nearly thirty-eight thousand fans. They won the NL Wild Card that year too, and made their first playoff appearance since falling to the Cardinals in the 1982 World Series when they were still an American League franchise. This time, the Brewers fell to the Phillies in a four-game NL Division Series.

Interestingly, two Major League teams besides the Brewers have called Miller Park “home” during its short life. In 2007, the Indians hosted the Angels at Miller for an April series when an unusually snowy spring in Cleveland made a mess of the Indians’ first two weeks schedule. The Brewers were on the road and Miller was available, so MLB moved the series, and announced that all tickets would sell for $10. Only fifty-two thousand fans turned out for the three games, but at least the Indians’ weren’t home shoveling like the rest of Cleveland. In September of 2008, an even more historic home-away-from-home moment occurred at Miller, when the Astros moved two games to Milwaukee to escape the path of Hurricane Ike. Carlos Zambrano started one of the two games for the visiting Cubs and pitched the first neutral site no-hitter in baseball history. It was also the first no-no in Miller Park history. It was a shame, though, that only twenty-three thousand fans were on hand to see Big Z’s masterpiece.