UMBERTO ECO : THE PRAGUE CEMETERY (11 page)

Read UMBERTO ECO : THE PRAGUE CEMETERY Online

Authors: Umberto Eco

"This is the advent of the Antichrist," my grandfather mourned. He naturally blamed every event on Jewish intrigue, seeing Mordechai's darkest prophecies as being fulfilled.

My grandfather provided shelter for Jesuit fathers trying to escape the fury of the people, as they waited to be reinstated in some way among the lay clergy. In early 1849 many arrived secretly from Rome with appalling stories of what was happening down there.

Father Pacchi. After reading Sue's

The Wandering Jew

, I saw him as the incarnation of Father Rodin, the wicked Jesuit who moved about in the shadows, sacrificing every moral principle to the interests of the Society, perhaps because (like Father Rodin) Father Pacchi concealed his membership in the order by dressing in secular clothes, wearing a scruffy topcoat caked in old sweat and covered with dandruff, a neckerchief instead of a cravat, a black threadbare waistcoat and heavy shoes encrusted with mud, which he trampled inconsiderately into our fine carpets. He had a thin, pale, chiseled face, oily gray hair plastered over his temples, turtle eyes and thin purplish lips.

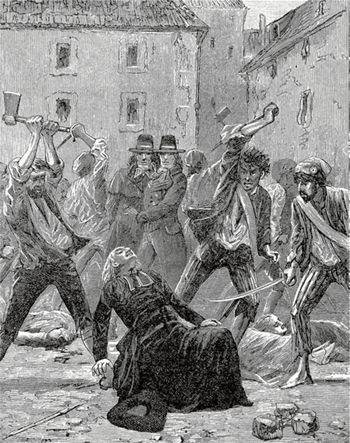

Not satisfied with the revulsion inspired simply by his presence at the table, Father Pacchi ruined everyone's appetite by recounting terrifying stories, uttered in sermonizing tones: "My friends," he said with tremulous voice, "but I have to tell you: the leprosy has spread from Paris. Louis Philippe was certainly no saint, but he was a bulwark against anarchy. I have seen the Roman people these past few days! Yet were they indeed the people of Rome? They were ragged and disheveled, thugs who would turn their backs upon heaven for a glass of wine. They are not people, they are a rabble, mixed with the vilest dregs from the cities of Italy and abroad, followers of Garibaldi and Mazzini, blind instruments for every evil. You know not how iniquitous are the abominations committed by the republicans. They enter churches and break open the reliquaries of martyrs, they scatter their ashes to the wind and use the urns as chamber pots. They rip out the altar stones and smear them with excrement, they deface the statues of the Virgin with their daggers, they cut the eyes out of the images of saints, and with charcoal they scrawl obscenities upon them. When a priest spoke out against the republic, they dragged him into a doorway, stabbed him, gouged out his eyes and tore out his tongue, and after disemboweling him, they wrapped his guts around his neck and strangled him. And do not imagine, even if Rome is liberated (already there is talk of help arriving from France), that Mazzini's followers will be defeated. They have spewed out from every province of Italy; they are shrewd and crafty, fraudsters and deceivers; they are daring, patient and determined. They will continue to congregate in the city's most secret haunts; their falsity and hypocrisy allow them to penetrate the secrets of government offices, the police, the army, the navy, the city strongholds."

"And my son is among them," cried my grandfather, crushed in body and spirit.

Excellent beef braised in Barolo then arrived at the table.

"My son will never understand the beauty of such a thing," he said. "Beef with onion, carrot, celery, sage, rosemary, bay leaf, clove, cinnamon, juniper, salt, pepper, butter, olive oil and, of course, a bottle of Barolo, served with polenta or puréed potato. Go on, fight the revolution. All taste for life is gone. You people want to be rid of the pope, and we'll end up being forced by that fisherman Garibaldi to eat

bouillabaisse niçoise

. What is the world coming to!"

Father Bergamaschi often went off, dressed in secular clothing, saying he would be away for a few days, without explaining where or why. Then I would go into his room, take out his cassock, dress myself up in it and admire myself in a mirror, moving about as if dancing — as if I were, heaven forbid, a woman, or as if I were imitating him. If it turns out I am Abbé Dalla Piccola, I have discovered here the distant origins of these theatrical tastes of mine.

In the pockets of the cassock I found some money (which the priest had obviously forgotten), and I decided to treat myself to a little gluttonous transgression and explore places in the city that I had often heard praised.

Thus dressed — and without realizing that in those days it was already a provocation— I headed offinto the labyrinth of Balôn, that part of Porta Palazzo then inhabited by the dregs of Turin's population, where the worst band of miscreants to infest the city were recruited. But on feast days Porta Palazzo market offered extraordinary entertainment. The people jostled and shoved, pressing around the stalls; servant girls flocked into the butcher shops; children stood spellbound in front of the nougat makers; gourmands purchased their poultry, game and charcuterie; and in the restaurants not a single table was free. In my cassock I brushed past women's flapping dresses, and from the corner of my eye, which I kept ecclesiastically fixed upon my crossed hands, I saw the faces of women wearing hats, bonnets, veils or headscarves, and felt bewildered by the bustle of carriages and carts, by the shouts, the cries, the uproar.

Excited by the exuberance, from which my grandfather and my father had until then kept me hidden, though for different reasons, I pushed my way to one of Turin's legendary places at that time. Dressed as a Jesuit, and mischievously enjoying the curiosity I aroused, I arrived at Caffè al Bicerin, close to the Sanctuary of the Consolata, to taste their milk, fragrant with cocoa, coffee and other flavors, served in a glass with a metal holder and handle. I was not to know that one of my heroes, Alexandre Dumas, would write about

bicerin

a few years later, but after only two or three visits to that magical place I learned all about that nectar. It originated from the

bavareisa

, except that, whereas in the

bavareisa

the milk, coffee and chocolate are mixed together, in a bicerin they stay in three separate layers (which remain hot), so you can order a

bicerin pur e fiur

, made with coffee and milk, pur e barba, with coffee and chocolate, or '

n poc 'd tut

, meaning a little of everything.

It was a magnificent place, with its wrought-iron front edged by advertising panels, its cast-iron columns and capitals and, inside, wooden

boiseries

decorated with mirrors, marble-topped tables and, behind the counter, almond-scented jars with forty different types of confections. I enjoyed standing there watching, particularly on Sundays, when this drink was nectar for those who had fasted in preparation for communion and needed some sustenance on leaving the Consolata — and a

bicerin

was also much prized during the Lenten fast, since hot chocolate was not regarded as food. What hypocrites.

Apart from the pleasures of coffee and chocolate, what I most enjoyed was appearing to be someone else; the thought that people had no idea who I really was gave me a sense of superiority. I had a secret. But I had to limit and finally halt these adventures. I was frightened of bumping into my comrades, who certainly didn't think of me as a religious zealot and believed that I too was fired by their enthusiasm for the Carbonari.

These aspiring national liberators generally gathered at the Osteria del Gambero. In a dark narrow street, over a still darker doorway, a sign with a golden prawn read

Osteria del Gambero d'Oro, Good Wine & Good Food

. Inside was a room that also served as kitchen and wine cellar. Amid smells of salami and onions, customers drank and sometimes played

morra

. More often than not we passed the night, conspirators without a plot, dreaming of imminent insurrections. I had learned to enjoy good food at my grandfather's house, and all that could be said about the Gambero d'Oro was that you could satisfy your hunger, provided you were not too fussy. But I needed to get out into society and escape from our Jesuit guests, so the Gambero's greasy food and my jovial friends were preferable to somber dinners at home.

We would leave toward dawn, our breath heavy with garlic and our hearts filled with patriotic ardor, losing ourselves in a comforting mantle of fog, excellent for avoiding the attention of police spies. Sometimes we crossed the Po and climbed up to look back over the roofs and bell towers floating on the mist that covered the plain, while the faraway Basilica of Superga, already glinting in the sun, seemed like a lighthouse in the middle of the sea.

But we students didn't just talk about the nation to come. We talked, as happens at that age, about women. Each in turn, eyes gleaming, recalled looking up at a balcony and catching a smile, touching a hand while passing on a staircase, a dried flower dropped from a missal and picked up (the braggart claimed) while it still held the perfume of the hand that had placed it between those sacred pages. I feigned annoyance, and acquired the reputation of being a Mazzinian of strict and upright morals.

Except that one evening the most licentious of our companions announced that he had found in a chest in his attic, well hidden by his shameless, dissipated father, several of those volumes which in Turin were known (in French) as

cochons

, and not daring to lay them out on the greasy table of the Gambero d'Oro, he had decided to lend them to each of us in turn. When it came to me, I could hardly refuse.

Apart from the pleasures of coffee and chocolate, what

I most enjoyed was appearing to be someone else.

Late one night, I leafed through those volumes, which must have been precious and valuable, bound as they were in morocco, spines with raised cords and red title labels, gilt page edges, gilt fleurons on the covers and some with coats of arms. They had titles such as

Une veillée de jeune fille and Ah! monseigneur, si Thomas nous voyait

! and I shuddered as I turned the pages and found engravings that sent streams of sweat trickling from my hair down my cheeks and neck: young women who lifted their skirts to reveal buttocks of dazzling whiteness, offered for the abuse of lascivious men — nor did I know whether to be more disturbed by their brazen rotundity or by the almost virginal smile of the young girl, whose head was turned immodestly toward her violator, her face illuminated with mischievous eyes, framed by jet-black hair parted into two side-knots; or still more terrifying, three girls on a couch with their legs open to display what should have been the natural defense of their virginal pudenda, one of them offering it to the right hand of a man with ruffled hair, who at the same time was penetrating the girl lying shamelessly beside her, while the third girl had her crotch nonchalantly exposed and with her lefthand was parting her cleavage with subtle prurience through her ruffled corset. And then I found the curious caricature of a priest with a wart-covered face, which on closer inspection was made up of naked men and women variously entwined, and penetrated by enormous male members, many of which hung in a line over the nape of the neck as if to form, with their testicles, a thick head of hair that ended in heavy ringlets.