UMBERTO ECO : THE PRAGUE CEMETERY (44 page)

Read UMBERTO ECO : THE PRAGUE CEMETERY Online

Authors: Umberto Eco

I go to Doctor Du Maurier to find out more about Diana: "You have to understand, Doctor, my confraternity cannot help this girl unless we know where she comes from, who her parents are."

Du Maurier looks at me blankly. "I don't know anything, I've told you. She was entrusted to me by a relative who is dead."

"And the address of this relative?"

"It may seem strange, but I no longer have it. There was a fire in my office a year ago and many papers were lost. I know nothing of her past."

"Did she come from America?"

"Maybe, but she speaks French without any accent. Tell your charitable ladies not to concern themselves too much, since it's quite impossible for the girl to escape her current condition and live a normal life. And they must treat her gently, allowing her to end her days peacefully — I tell you, she won't survive very long in such an advanced stage of hysteria. Before long she'll have a violent inflammation of the uterus and medical science will be powerless to do any more."

I am convinced he is lying. Perhaps he too is a Palladian (so much for the Grand Orient!) and had agreed to deal with an enemy of the sect, walling her up alive. But these are mere conjectures. It is a waste of time talking any longer to Du Maurier.

I question Diana, in both her first and her second state. She seems to recall nothing. Around her neck she wears a gold chain with a medallion that has the picture of a woman whom she greatly resembles. I notice that the medallion can be opened, and I repeatedly ask her to show me what is inside. But she emphatically refuses, with an expression of fear and wild determination. "My mother gave it to me" is all she says each time. It must now be four years since Taxil began his campaign against the Freemasons. The reaction from the Catholic world has gone far beyond our expectations: in 1887 Taxil is called by Cardinal Rampolla to a private audience with Pope Leo XIII. Official approval of his battle, and the start of a great publishing success. And economic success.

Around that time I received a curt but eloquent note: "Most reverend Abbé, it seems that matters are going well beyond what we intended. Please deal with the situation. Hébuterne."

There is no turning back. I'm not talking here about the author's earnings, which continue to flood in, but of the tensions and alliances that have been created with the Catholic world. Taxil is now a hero in the fight against Satanism, and would not want to relinquish that position.

Meanwhile, another short note arrived, from Father Bergamaschi: "All seems to be going well. But the Jews?"

Father Bergamaschi had already been urging that Taxil's scandalous revelations should be about not just Freemasonry but also the Jews. Yet both Diana and Taxil were silent on that score. I wasn't surprised about Diana. Perhaps there were fewer Jews in the America she came from than there were here, so the problem seemed irrelevant. But Freemasonry was full of Jews, and I pointed this out to Taxil.

"And how should I know?" he answered. "I've never come across Jewish Masons, or at least not knowingly. I've never seen a rabbi in a lodge."

"They don't go there dressed as rabbis. But I've been told by a certain well-informed Jesuit father that Monsignor Meurin, who's not just any priest but an archbishop, will prove in a forthcoming book that all the Masonic rituals have kabbalistic origins, and that it's the Jewish Kabbalah which leads Masons to demonolatry."

"Then let us leave it to Monsignor Meurin to speak. We have enough irons in the fire."

Taxil's reluctance surprised me (is he Jewish? I wondered), until I discovered that in the course of his various journalistic and bookselling enterprises he was prosecuted on many occasions for defamation or obscenity and had had to pay some very harsh fines. He was therefore heavily in debt to several Jewish moneylenders, from whom he had been unable to release himself (not least because he freely spent the substantial earnings from his new anti-Masonic activity). He feared that these Jews, who were content for the moment, might send him off to debtors' prison if they felt they were under attack.

Was it just a question of money, though? Taxil was a scoundrel, but he did have feelings; for example, he was closely attached to his family. And for some reason he felt compassion toward Jews, the victims of many persecutions. He used to say that the popes had protected the Jews in the ghetto, if only as second-class citizens.

Success had gone to his head: believing himself to be the herald of Catholic monarchist and anti-Masonic thought, Taxil decided to turn to politics. I was unable to follow him through all his intrigues, but he stood as candidate for a district council in Paris and found himself in competition, and in dispute, with an important journalist called Drumont, who was involved in a violent campaign against Jews and Freemasons. Drumont had a considerable following among people in the Church, and began to insinuate that Taxil was a schemer — and perhaps the word "insinuate" is too weak.

In 1889, Taxil had written a pamphlet against Drumont, and, not knowing what accusations to make (both of them denouncing the Masons), he described Drumont's phobia of Jews as a form of mental alienation. And he got carried away with some recriminations about the Russian pogroms.

Drumont was a born polemicist and replied with an attack in which he spoke sarcastically about this self-appointed champion of the Church, a man who received embraces and congratulations from bishops and cardinals yet only a few years earlier had written outrageous filth about the pope and the clergy, not to mention Jesus and the Virgin Mary. But there was worse.

I had visited Taxil several times at his house, where on the ground floor he had once had his anticlerical bookshop, and we were often interrupted by his wife, who would come and whisper in his ear. As I later discovered, many unrepentant anticlericals still went to that address in search of anti-Catholic works, copies of which Taxil, though now a devout Catholic, still had in his storehouse in such vast quantities that he couldn't easily destroy them. And so, with great discretion, he continued to exploit this excellent line of business, always sending his wife out and never appearing in person. I never harbored illusions about the sincerity of his conversion: the only philosophical principle he adhered to was

Pecunia non olet.

Except that Drumont had found out about this, and so attacked his Marseillais rival not only for being linked in some way with the Jews, but also for remaining an unrepentant anticlericalist. This was enough to raise grave doubts among our more God-fearing readers.

It was time to strike back.

"Taxil," I said, "I'm not interested in why you don't want to be personally involved against the Jews, but isn't it possible to bring in someone else who can deal with the matter?"

"Provided I'm not directly involved," Taxil replied. Then he added: "In fact my own revelations are no longer enough, nor even the nonsense our Diana tells us. We've created a readership that wants more. Perhaps they no longer read me to learn about conspiracies by the enemies of the Cross, but purely and simply out of love for a good story, as in those tales of intrigue where the reader is drawn to the side of the criminal."

And that is how Doctor Bataille was born.

Taxil had discovered, or refound, an old friend, a naval doctor who had traveled widely in exotic countries, nosing about here and there among the temples of various religious conventicles, but who above all had a boundless knowledge when it came to adventure stories, including the books of Boussenard and the fanciful accounts of Jacolliot, such as

Le spiritisme dans le monde and Voyage aux pays mystérieux.

I fully approved of the idea of looking for new subjects in the world of fiction (and from your diaries I notice that you yourself have been much influenced by Dumas and Sue). People are voracious readers of travel adventures and crime stories. They read for simple pleasure, then quickly forget what they have learned, and when they're told about something they have read in a novel as if it were true, they have just a vague recollection of having heard some mention of it, and their ideas are confirmed.

The man Taxil had rediscovered was Dr. Charles Hacks, who had been a specialist in cesarean birth and had published several books on the merchant navy, but had never exploited his talent as a storyteller. He seemed to suffer from serious bouts of alcoholism and was clearly penniless. From what he'd told Taxil, he was about to publish an important attack on religions and Christianity, which he described as "crucifixion hysteria." But when presented with Taxil's offer, he was ready to write a thousand pages against devil worshipers, to the glory and defense of the Church.

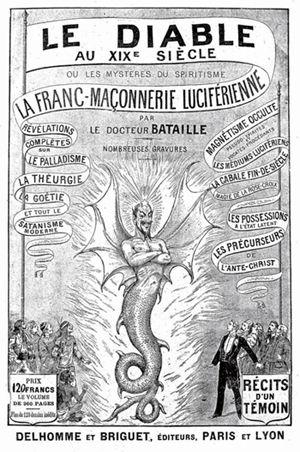

I remember that in 1892 we began a mammoth work, a series in 240 installments to be published over about thirty months, titled

Le diable au XIXe siècle.

It had a great sneering Lucifer on the cover, with the wings of a bat and the tail of a dragon, and was subtitled

The mysteries of modern Satanism, occult magnetism, Luciferian mediums, fin-de-siècle Kabbalah, Rosicrucian magic, possessions in the latent state, the precursors of the Antichris

t — all attributed to a mysterious Doctor Bataille.

The work contained nothing that hadn't been written elsewhere, as was intended: Taxil or Bataille had plundered all the previous literature and had built up a hodgepodge of subterranean cults, devilish apparitions, spine-chilling rituals, more Templar liturgies featuring the usual Baphomet, and so forth. The illustrations too had been copied from other books on occult science, which illustrations themselves had been copied. The only previously unpublished pictures were the portraits of Masonic grand masters, which were like those posters found in American prairie towns showing outlaws who had to be tracked down and handed over to the law, dead or alive.

Work progressed at a frenetic pace. Hacks-Bataille, after liberal doses of absinthe, described his inventions to Taxil, who wrote them up and embellished them; or Bataille busied himself over details concerning medical science, the art of poisoning and the description of cities and esoteric rites that he had actually seen. Meanwhile, Taxil embroidered upon Diana's latest delusions.

Bataille, for example, began by depicting the rock of Gibraltar as a spongy mass crisscrossed with passageways, cavities and subterranean caves where some of the most blasphemous sects celebrated their rituals, describing the Masonic antics of the Indian sects and the apparitions of Asmodeus, while Taxil gave a profile of Sophia Sapho. Having read the

Dictionnaire infernal

by Collin de Plancy, he suggested that Sophia had revealed that there were 6,666 legions, each legion consisting of 6,666 demons. Although he was drunk by this time, Bataille managed to work out that the total number of devils and she-devils was 44,435,556. We checked his calculation, admitting with surprise that he was right, and he banged his fist on the table and shouted, "You see then, I'm not drunk!" He was so pleased with himself that he slid under the table.

. . . a mammoth work titled

Le diable au XIXe siècle.

It had

a great sneering Lucifer on the cover, with the wings of a

bat and the tail of a dragon.