Understanding Business Accounting For Dummies, 2nd Edition (92 page)

Read Understanding Business Accounting For Dummies, 2nd Edition Online

Authors: Colin Barrow,John A. Tracy

Tags: #Finance, #Business

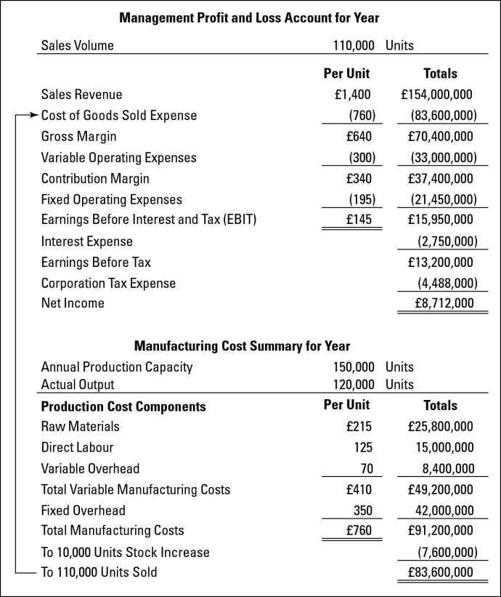

The information in the manufacturing cost summary schedule below the profit and loss account (see Figure 12-2) is highly confidential and for management eyes only. Competitors would love to know this information. A company may enjoy a significant cost advantage over its competitors and definitely would not want its cost data to get into the hands of its competitors.

Unlike a retailer, a manufacturer does not

purchase

products but begins by buying the raw materials needed in the production process. Then the manufacturer pays workers to operate the machines and equipment and to move the products into warehouses after they've been produced. All this is done in a sprawling plant that has many indirect overhead costs. All these different production costs have to be funnelled into the product cost so that the product cost can be entered in the stock account, and then to the cost of goods sold expense when products are sold.

Figure 12-2:

Example for determining product cost of a manufac-turer.

Allocating costs properly: Not easy!

Two vexing issues rear their ugly heads in determining product cost for a manufacturer:

Drawing a defining line between manufacturing costs and non-manufacturing operating costs:

The key difference here is that manufacturing costs are categorised as product costs, whereas non-manufacturing operating costs are categorised as period costs (refer to ‘Product versus period costs' earlier in this chapter). In calculating product cost, you factor in only manufacturing costs and not other costs. Period costs are recorded right away as an expense - either in variable operating expenses or fixed operating expenses for the example shown in Figure 12-2.

Wages paid to production line workers are a clear-cut example of a manufacturing cost. Salaries paid to salespeople are a marketing cost and are not part of product cost; marketing costs are treated as period costs, which means these costs are recorded immediately to the expenses of the period. Depreciation on production equipment is a manufacturing cost, but depreciation on the warehouse in which products are stored after being manufactured is a period cost. Moving the raw materials and works-in-progress through the production process is a manufacturing cost, but transporting the finished products from the warehouse to customers is a period cost. In short, product cost stops at the end of the production line - but every cost up to that point should be included as a manufacturing cost. The accumulation of direct and variable production costs starts at the beginning of the manufacturing process and stops at the end of the production line. All fixed and indirect manufacturing costs during the year are allocated to the actual production output during the year.

If you mis-classify some manufacturing costs as operating costs, your product cost calculation will be too low (refer to ‘Calculating product cost' later in this chapter).

Whether to allocate indirect costs among different products, or organisational units, or assets:

Indirect

manufacturing

costs must be allocated among the products produced during the period. The full product cost includes both direct and indirect manufacturing costs. Coming up with a completely satisfactory allocation method is difficult and ends up being somewhat arbitrary - but must be done to determine product cost. For non-manufacturing operating costs, the basic test of whether to allocate indirect costs is whether allocation helps managers make better decisions and exercise better control. Maybe, maybe not. In any case, managers should understand how manufacturing indirect costs are allocated to products and how indirect non-manufacturing costs are allocated, keeping in mind that every allocation method is arbitrary and that a different allocation method may be just as convincing. (See the sidebar ‘Allocating indirect costs is as simple as ABC - not!')

Calculating product cost

The basic equation for calculating product cost is as follows (using the example of the manufacturer from Figure 12-2):

£91.2 million total manufacturing costs ÷ 120,000 units production output = £760 product cost per unit

Looks pretty straightforward, doesn't it? Well, the equation itself may be simple, but the accuracy of the results depends directly on the accuracy of your manufacturing cost numbers. And because manufacturing processes are fairly complex, with hundreds or thousands of steps and operations, your accounting systems must be very complex and detailed to keep accurate track of all the manufacturing costs.

As we explain earlier, when introducing the example, this business manufactures just one product. Also, its product cost per unit is determined for the entire year. In actual practice, manufacturers calculate their product costs monthly or quarterly. The computation process is the same, but the frequency of doing the computation varies from business to business.

Allocating indirect costs is as simple as ABC - not!

Accountants for manufacturers have developed loads of different methods and schemes for allocating indirect overhead costs, many based on some common denominator of production activity, such as direct labour hours. The latest method to get a lot of press is called

activity-based costing

(ABC).With the ABC method, you identify each necessary, supporting activity in the production process and collect costs into a separate pool for each identified activity. Then you develop a

measure

for each activity - for example, the measure for the engineering department may be hours, and the measure for the maintenance department may be square feet. You use the activity measures as

cost drivers

to allocate cost to products. So if Product A needs 200 hours of the engineering department's time and Product B is a simple product that needs only 20 hours of engineering, you allocate ten times as much of the engineering cost to Product A.The idea is that the engineering department doesn't come cheap - including the cost of their computers and equipment as well as their salaries and benefits, the total cost per hour for those engineers could be £100 to £200. The logic of the ABC cost-allocation method is that the engineering cost per hour should be allocated on the basis of the number of hours (the driver) required by each product. In similar fashion, suppose the cost of the maintenance department is £10 per square foot per year. If Product C uses twice as much floor space as Product D, it will be charged with twice as much maintenance cost.

The ABC method has received much praise for being better than traditional allocation methods, especially for management decision making, but keep in mind that it still requires rather arbitrary definitions of cost drivers - and having too many different cost drivers, each with its own pool of costs, is not too practical. Cost allocation always involves arbitrary methods. Managers should be aware of which methods are being used and should challenge a method if they think that it's misleading and should be replaced with a better (though still somewhat arbitrary) method. We don't mean to put too fine a point on this, but to a large extent, cost allocation boils down to a ‘my arbitrary method is better than your arbitrary method' argument.

Note:

Cost allocation methods should be transparent to managers who use the cost data provided to them by accountants. Managers should never have to guess about what methods are being used, or have to call upon the accountants to explain the allocation methods.