Understanding Business Accounting For Dummies, 2nd Edition (90 page)

Read Understanding Business Accounting For Dummies, 2nd Edition Online

Authors: Colin Barrow,John A. Tracy

Tags: #Finance, #Business

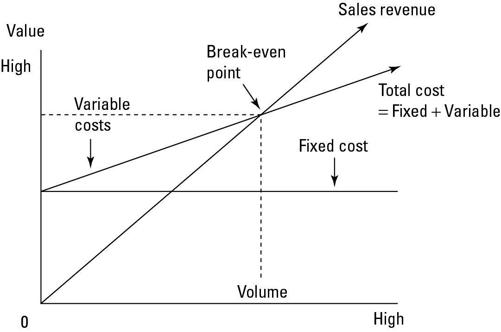

Every picture is worth a thousand words, or so it is said. Well, ‘finance' and ‘pictures' are words that don't come together too often, but they certainly do when you look at costings.

Take a look at Figure 12-1. The bottom horizontal axis represents volume, starting at 0 and rising as the company produces more product. The vertical axis represents value, starting at 0 and rising, as you'd expect, with any increase in volume. The horizontal line in the middle of the chart represents

fixed costs

- those costs that remain broadly unchanged with increases in volume, rents, and so on. The line angling upwards from the fixed cost line represents the

variable cost

- the more we produce, the higher the cost is. We arrive at the total costs by adding the fixed and variable costs together.

Figure 12-1:

A break-even chart.

On the hopeful assumption that our sales team has been hard at work, we should then see sales revenue kicking in. The line representing those sales starts at 0 (no sales means no money is coming in) then rises as sales grow. The crucial information this chart shows is the

break-even

point,

when total costs have been covered by the value of sales revenue and the business has started to make profit. The picture makes it easier to appreciate why lowering cost, either fixed or variable, or increasing selling prices, helps a business to break even at lower volumes and hence start making profit sooner and be able to make even more profit from any given amount of assets.

Conversely, a business that only reaches break even when sales are so high that there is virtually no spare capacity is shown as being vulnerable, because that business has a small

margin of safety

if events don't turn out as planned.

The SCORE Web site (

www.score.org

) offers a downloadable Excel spreadsheet that enables you to experiment with changes in fixed and variable cost levels, sales volumes, and selling prices to arrive at an optimal cost structure. Go to the homepage and click on ‘Business Tools', ‘Template Gallery', and ‘Breakeven Analysis' to access the spreadsheet.

Relevant versus irrelevant (sunk) costs

Relevant costs:

Costs that should be considered when deciding on a future course of action. Relevant costs are

future

costs - costs that you would incur, or bring upon yourself, depending on which course of action you take. For example, say that you want to increase the number of books that your business produces next year in order to increase your sales revenue, but the cost of paper has just shot up. Should you take the cost of paper into consideration? Absolutely: That cost will affect your bottom-line profit and may negate any increases in sales volume that you experience (unless you increase the sales price). The cost of paper is a relevant cost.

Irrelevant (or sunk) costs:

Costs that should be disregarded when deciding on a future course of action: If brought into the analysis, these costs could cause you to make the wrong decision. An irrelevant cost is a vestige of the past; that money is gone, so get over it. For example, suppose that your supervisor tells you to expect a load of new recruits next week. All your staff members use computers now, but you have loads of typewriters gathering dust in the cupboard. Should you consider the cost paid for those typewriters in your decision to buy computers for all the new staff? Absolutely not: That cost should have been written off and is no match for the cost you'd pay in productivity (and morale) for new employees who are forced to use typewriters.

Generally speaking, fixed costs are irrelevant when deciding on a future course of action, assuming that they're truly fixed and can't be increased or decreased over the short term. Most variable costs are relevant because they depend on which alternative is decided on.

Fixed costs are usually irrelevant in decision-making because these costs will be the same no matter which course of action you decide upon. Looking behind these costs, you usually find that the costs provide

capacity

of one sort or another - so much building space, so many machine-hours available for use, so many hours of labour that will be worked, and so on. Managers have to figure out the best overall way to utilise these capacities.

Separating between actual, budgeted, and standard costs

Actual costs:

Historical costs, based on actual transactions and operations for the period just ended, or going back to earlier periods. Financial statement accounting is based on a business's actual transactions and operations; the basic approach to determining annual profit is to record the financial effects of actual transactions and allocate historical costs to the periods benefited by the costs.

Budgeted costs:

Future costs, for transactions and operations expected to take place over the coming period, based on forecasts and established goals. Note that fixed costs are budgeted differently than variable costs - for example, if sales volume is forecast to increase by 10 per cent, variable costs will definitely increase accordingly, but fixed costs may or may not need to be increased to accommodate the volume increase (see ‘Fixed versus variable costs', earlier in this chapter). Chapter 10 explains the budgeting process and budgeted financial statements.

Standard costs:

Costs, primarily in manufacturing, that are carefully engineered based on detailed analysis of operations and forecast costs for each component or step in an operation. Developing standard costs for variable production costs is relatively straightforward because many of these are direct costs, whereas most fixed costs are indirect, and standard costs for fixed costs are necessarily based on more arbitrary methods (see ‘Direct versus indirect costs' earlier in this chapter).

Note:

Some variable costs are indirect and have to be allocated to specific products in order to come up with a full (total) standard cost of the product.