Unknown

Authors: Unknown

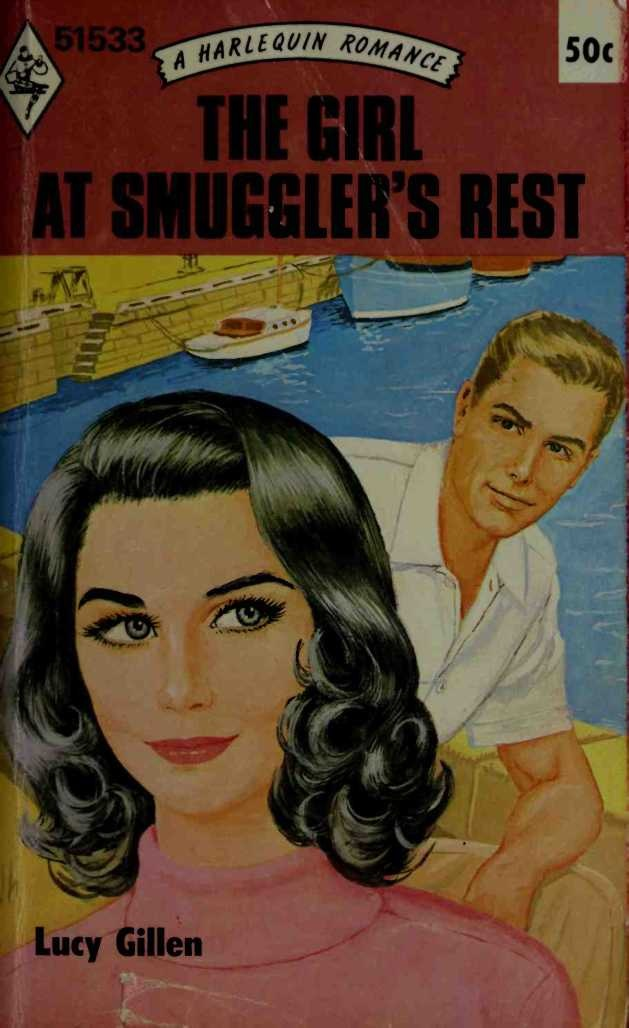

THE GIRL AT SMUGGLER'S REST

Lucy Gillen

"Don't get too involved with Jamie,”

John Miller warned Katie

.

"I wouldn't like either of you getting into anything you'd be sorry for

.

"

The "iceberg” of a John seemed to regard himself as his brother's keeper, Katie considered — and she wondered wryly what John would think if he knew that it was himself he should be worrying about!

IT was not, Katie told herself, as if she had ever liked Aunt Cora very much; or that she had seen anything of her since her parents died. Aunt Cora, her mother’s aunt in fact, had never seemed to approve of the way in which her niece and her husband had brought up their only child. Katie, who had been christened Katherine but could not remember the last time she had been called by it, remembered the irascible old lady as a very infrequent visitor to their home who always cast an air of tension over the usually carefree household. Katie’s father had once said that Aunt Cora was quite rich, but as far as he was concerned she could do what she pleased with her money, if only she would stay away from them.

Katie smiled to herself at the memory; as if her father could afford to talk that way about money! It was spent as fast as it came in and life had been very gay and carefree, with never a thought for tomorrow, until one day, almost three years ago, when she had returned home from a party to find a policeman waiting on the doorstep for her. Killed instantly, both of them; that was her only consolation—that one of them had not been left to grieve alone, for they had loved one another as much after twenty-one years of marriage as they had at the beginning, and Katie, at twenty, had been left alone in the world except for Aunt Cora. "

She jolted herself back to reality as the train pulled into Mare Green Station. There were one or two other people alighting at the same time and all of them seemed certain of their destinations, a certainty not shared by Katie. She picked up her case and made her way across the platform to the gate. Her arrival there coincided with that of another passenger and the collision was inevitable.

“Sorry,” the voice was deep and genuinely apologetic, but before she could recover her breath, he had gone through the barrier and was striding towards the only remaining taxi.

She emerged from the dim little ticket hall just as it pulled away, with the man seated, complacently she was sure, in the back. She had a brief glimpse of a fair, good-looking face with a straight mouth and vivid blue eyes, before the taxi turned out of the station’s gravel yard and was gone.

“Well!” She sat down on the narrow wooden bench that ran along the front of the ticket hall, her feelings plain on her face.

“Hard luck, miss.” The ticket collector had followed her through to the yard and stood looking at her, a grin on his leathery face that did nothing to improve her temper.

“I don’t find it very amusing,” she told him icily. “When will there be another one?”

He shrugged his thin shoulders casually. “Any time, I should think,” he said. “Nearest one as would want a taxi would be Mrs. Carter and she was off among the first, so ’ers should be back pretty soon.” He leaned against the doorway of the building, his squinty eyes admiring her openly. She was not very tall, what the magazines describe as petite, with a mass of black hair that framed a face frankly beautiful. A creamy skin contrasting with the dark hair and black-fringed grey eyes, now stormily dark, made her a girl worth looking at.

“How soon is pretty soon?” she asked.

“Right now.” He flapped a listless hand at the yard entrance and she turned and saw with relief a taxi just turning in. The driver pulled up, looking curiously at her from under the shiny peak of his cap.

“Where to, miss?” he asked, opening the door for her without getting out of his seat.

“Smuggler’s Rest, please.” She gave the oddly unsuitable name of her aunt’s house, and bundled her suitcase into the taxi as best she could then climbed in herself. “It’s in Webber Road.”

“I know it, miss, not to worry.” That at least was reassuring, she thought as he turned right, out of the station yard and along a narrow road and before long Katie caught a glimpse of the sea between the little stone cottages that lined the road and huddled together as if in secret congress. The driver half turned his head and spoke through the open window between them. “You’ll likely be Miss Manson’s niece, I reckon?” he said conversationally.

“I am,” she admitted, trying to imagine Aunt Cora on confiding terms with a taxi driver and failing to do so.

He nodded. “I heard you was comin’,” he said. “My sister Alice obliges Miss Manson.”

“Oh, I see.” She smiled to herself. In a place as small as Mare Green, that had very few visitors, she supposed that everyone would know everyone else’s business inevitably. She wondered what Aunt Cora’s reaction would have been to the knowledge that her daily help was passing on her affairs to her brother.

“Not far now, miss,” he said cheerfully. “You been here before?”

“No.” She shook her head and watched, regretfully, as the sea was left behind on their right. Webber Road lay back from the sea front and so avoided the worst of the sometimes severe storms that had, on occasion, crashed their way into the tiny cottages huddled defiantly on the low-lying quay.

Smuggler’s Rest, like its neighbours, was sturdily built of grey stone, mellowed over the years to a softer bluey shade by the salt air. Its garden, neat and rather severe like Katie remembered Aunt Cora herself, had the usual shrubs and rather dejected-looking trees to be found in seaside gardens and a tidy-edged path of paving to the front door. Its name she thought was most unsuitable.

Aunt Cora herself opened the door as she approached, a shrill-voiced pekinese making protest at her heels. The old lady eyed her critically from the top of her black head to the toes of her pretty but flimsy pink shoes. “Hello, Aunt Cora.” She was uncertain whether or not to kiss the wrinkled old face, so she brushed her lips briefly against the old lady’s cheek and clasped her in greeting.

“I’m glad to see you, Katherine, although you’re rather later than I anticipated.” The shrewd grey eyes had not softened with age and Katie wondered if they ever would; she had also forgotten that Aunt Cora was the one person who

always

called her Katherine.

The room her aunt showed her into was surprisingly gay and bright when she considered the old lady’s abhorrence of anything frivolous. It was white-painted and papered with a pattern of soft blues and pinks, with curtains and a quilt that matched perfectly.

“I hope you like your room,” Aunt Cora said, and turning, Katie surprised an anxious look that seemed out of character with the woman she remembered.

“It’s lovely,” she said delightedly. “So bright and pretty.”

“I’m afraid I’m not familiar with the modem trends in interior decoration.” She held her hands at her waist folded primly, defying criticism. “I could only follow my own inclination in the matter.”

Katie smiled, feeling a sudden warm affection for the old lady, “If this is the result, Aunt Cora, I can only say that you have very good taste. It’s lovely.” She walked across the room to the window, screened with soft falls of white net. The garden this side of the house was more colourful than at the front, and stretched much further than Katie had anticipated, it was gay with brightly coloured flowers and a smooth green lawn, and it was divided from its neighbours on either side by a low wooden fence.

Katie stared curiously from behind her screen at the occupant of the garden to the left of her aunt’s. A striped deck chair had been erected on the stretch of lawn and a man sat, or more accurately sprawled, full length in it, his eyes closed against the bright sun.

“Aunt Cora," she spoke over her shoulder, still watching the reclining man curiously, ‘who is your neighbour?”

Her aunt joined her and she too looked down into the garden next door. “His name is Miller,” she said, “John Miller. He took over the house a little under two months ago.”

“Oh, he’s new.” Katie thought she detected a faint note of disapproval in her aunt’s voice, though she had voiced none. Katie had the feeling, suddenly, that the man was aware of their scrutiny, and as if to confirm her thought, he turned his head and looked up at the window.

Aunt Cora moved back hastily, out of view, embarrassed at being caught watching, but Katie, remembering her wait at the station, put one hand to the filmy curtain pulling it aside slightly. She gazed down from behind the screening net and met the stare of the vivid blue eyes. “Katherine!” Aunt Cora protested, scandalised. “Please come away from the window! That is no way to behave, it is an invasion of privacy.”

Katie stepped back smiling. “What does he do, for a living, Aunt Cora, do you know?”

Aunt Cora tightened her thin mouth. “I believe he paints,” she said coldly, “although I would have thought that a man of his age and education could have found a more productive occupation than painting.”

Katie frowned. “Painting?” she said. “He doesn’t look like an artist to me.” She chanced a further look at the relaxed figure in the deck chair. “He was on the same train that I came on,” she said. “He took the last available taxi, after almost knocking me down, so I suppose his manners are ‘arty' at least.”

“He isn’t here all the time,” Aunt Cora said. “He goes away fairly often, so I suppose he may have some other business elsewhere, but my daily woman informs me that he

is

an artist, and quite a good one.”

“Mmm.” Katie looked dubious, wondering if the informant was the taxi driver’s sister Alice. “He still doesn’t look like an artist to me, he’s too clean and tidy-looking.”

After dinner that evening, when Katie found her aunt unexpectedly good company, she decided that she would take a stroll as far as the quay—it was only a few minutes’ walk, her aunt informed her, and the air was still heavily warm and the sun bright enough to make sun-glasses advisable against the glare off the water.

Mare Green was very quiet, little more than a village, straggling along the stone quay and up to the low cliffs, overhanging the sea like frowning eyebrows. There must be very little except fishing, she thought, to employ the menfolk, and her aunt had told her that dwindling shoals drove more and more of them inland every year, until the trawler fleet was now reduced to a sparse four.

Of later years more large houses had been built as retired people discovered its quiet charm and moved in. The change to a more residential area made domestic work available to the women, too, and eased the financial problems a little.

One or two of the cottages, Katie noticed too, offered accommodation or bed and breakfast at reasonable terms. She walked the length of the quay, past the anchored trawlers preparing for their next trip, and drew many complimentary glances from the sea-sharp eyes of the men as she passed. The stone of the quay gave way to grass and led to a sandy path safely hack from the edge of the cliff. To her left as she left the quay she saw a very large house, lying well back from any danger of flooding from the sea, its tree-shaded gardens cool and shady in the late sun.

Climbing slowly on the sandy path she was soon as high as the roofs of the cottages below, the turf on the cliffs springy and warm-scented under her feet, dotted with hardy wild flowers and spiky gorse that defied the salt-laden air to exist. By some standards the cliffs were not high, but they gave Katie a feeling of freedom as she sat up there and looked down at the placid sea, winking lazily as it rolled to the foot of the cliffs and was turned back again.

She had been there, she supposed, about twenty minutes, and the warmth was beginning to go from the sun as the first cool of the evening came in from the sea. She glanced at her wrist-watch and got to her feet, wondering if Aunt Cora would worry about her if she was too late coming back. Thinking about Aunt Cora and almost running down the path to the quay, Katie nearly collided with someone coming the other way. Strong fingers gripped her arms above the elbows and halted her before the collision occurred. “Oh!” She looked up into the vivid blue eyes of John Miller narrowed against the dying sun.

“Don’t you ever look where you’re going?” The voice was deep but incisive, clipping the words short as if he was out of patience.

She eased the hard grip and moved away from him, her face flushing angrily. Close to he was even better looking than at a distance; the fine-boned face tanned to a golden brown, contrasting with the very fair hair and uncannily blue eyes. “I might,” she said icily, “ask the same question of you, but at least this time you can’t commandeer the only taxi and leave me stranded.”

“Scarcely stranded, I think,” he said, his eyebrows raised at her exaggeration. “And the rule is first come, first served.” Before she could reply, and without another word, he walked past her and up the cliff path leaving her standing staring after him.

Katie found Bridie, Aunt Cora’s little pekinese dog, rather more uncertain in temper than Aunt Cora herself, and being asked to walk the little brute she felt was the last straw. However, since the old lady pleaded a headache, the following morning found Katie, with Bridie safely on a lead, walking down Webber Road. It was a lovely morning, bright and clear and very warm, so that Katie turned towards the quay, seeking a cooler breeze, despite Bridie’s snuffling protests.