Victor Fleming: An American Movie Master (Screen Classics) (38 page)

Read Victor Fleming: An American Movie Master (Screen Classics) Online

Authors: Michael Sragow

On location in San Antonio for the lost epic

The Rough Riders

(1927). George Bancroft holds a cigarette in one hand and his army hat in the other; James Wong Howe sports a white cap; Henry Hathaway, his head popping out of the crowd at his director’s feet, awaits orders from Fleming, who holds the megaphone; and next to Fleming sits a visitor, Clara Bow. This photo was taken on September 15, 1926, when she announced she and Fleming were “engaged.”

Fleming directs Clark Gable and Vivien Leigh as they stroll down Peachtree Street in the studio-built Atlanta of

Gone With the Wind

(1939).

Producer David O. Selznick and Fleming confer over the troubled script.

Selznick, Leigh, Fleming, Carole Lombard, and Gable celebrate at the wrap party.

Judy Garland, Fleming, Myrna Loy, and Frank Morgan at Fleming’s going-away party on

The Wizard of Oz

(1939).

Sunday fun. Three members of the Moraga Spit and Polish Club: Gable, Ward Bond, and Fleming. Bel-Air, 1946.

Composer Jerome Kern visits Jean Harlow and Fleming on the set of Fleming’s first musical,

Reckless

(1935).

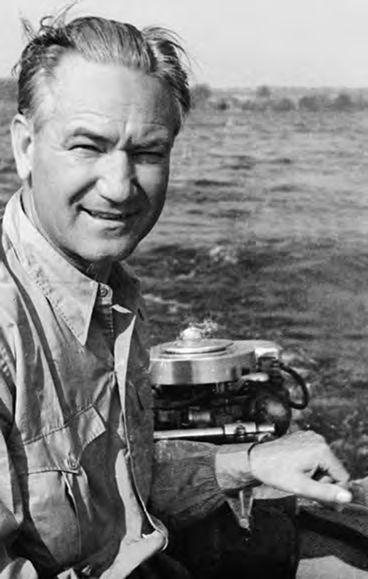

Fleming vacationing on the Rogue River in Oregon just before he went to work on

The Wizard of Oz

.

The strain of filming

Joan of Arc

shows in this 1947 portrait.

Stone is Stevenson’s Smollett to the unpliable upper lip. The film’s most audacious re-creation, though, may be Charles “Chic” Sale’s Ben Gunn, a crazy-eyed man in beard and tatters who’s been marooned on the island for three years and tells Jim that he can save his friends from Silver’s scurvy bunch. Sale moves with a painful, ecstatic angularity: it’s as if he’s astounded that his limbs are still attached to him. Mahin seizes on a subtle conversational tic in Stevenson’s book to compose a manner of speech for this castaway that’s riotously and emotionally true. Ben has been alone in the wilderness for so long that he transforms dialogue into monologue, and vice versa; “says you” and “says I” and “says he” punctuate every turn of his thought. Cooper gets the last laugh when Jim, in a bout of disgust that his friends take this loon quite seriously, mutters, “Says he, says them, says I, says nobody.”

Because of Cooper’s baby-faced youth, Fleming could cut down on Jim’s awkwardness and indecision without losing the boy’s alternately awestruck and despairing perspective. “At twelve going on thirteen,” Cooper said in his as-told-to autobiography,

Please Don’t Shoot My Dog

(1981), “it was the hardest work of my life, and some of the most unpleasant.” A lot of the unpleasantness came from co-starring with Wallace Beery, a prima donna who reacted to Cooper shooting some relatively harmless flash powder on his foot as if he’d been mortally wounded. Although Mahin thought “all the pirates were good,” he

“

didn’t think Beery was too good. He was so funny when he got the script. He said, ‘I don’t want to play this thing.’ Then somebody told him it was a great classic and then Beery was saying, ‘Oh, you can’t touch a word of this picture. This is a classic.’ ” Part of Beery’s bluster came from physical agony. “Beery was in terrible pain most of the time, with that leg strapped up in back of him,” said Cooper. “He just hated it. He’d pick scenes as often as possible sitting down, or sitting on the ground where they could dig a hole and stick his leg into it.”

For Cooper, his director provided most of the “bright spots.” He urged the young star to play old. “Fleming would tell me not to whine, to try to act more mature. It was the first time anyone had made me think about what I was doing, really to consider my character and how to make him come alive.” He later told Burt Prelutsky for

Emmy

magazine that Vidor and Fleming were his best directors, explaining, “When I was a kid, directors were always offering me bicycles whenever they wanted me to play a difficult scene. Instead of trying to communicate with me, they always tried bribes. By the time I was nine, I had eight or nine bikes in the garage. Fleming would speak to me like an adult. He would talk to me about the scene. I felt he respected me. As a result, I would break my neck to please him.”

Cooper proved wise beyond his years when it came to handling the rude, unpredictable Beery. Mahin said that in “the last shot of the last day of the picture,” Jim had to cry at Long John’s departure, and Fleming demanded, “Come on Jackie, you’ve got to get to work. Let’s stop fooling and finish the darned thing.” Cooper said, “Okay, Uncle Wally, be mean to me.” Beery let loose with “You little son of a bitch, I’ve had it with this leg . . . I’ve got pains, varicose veins.” Before long, Jackie, “crying like a trouper,” turned to his director and said, “All right, Vic, roll ’em!”