Victor Fleming: An American Movie Master (Screen Classics) (36 page)

Read Victor Fleming: An American Movie Master (Screen Classics) Online

Authors: Michael Sragow

Mahin and Fleming perceived

Treasure Island

as an elemental melodrama whose complexities derive from divided allegiances among the characters, not from psychological torture underneath their skin. “Character to the boy is a sealed book,” wrote Stevenson in an essay defending the emotional authenticity of his work; “for him a pirate is a beard, a pair of wide trousers, and a liberal complement of pistols . . . The characters are portrayed only so far as they realise the sense of danger and provoke the sympathy of fear.” The moviemakers bravely embellish Stevenson’s caricatures. Watch this movie at an impressionable age and it’s your

Treasure Island

for life. Watch the movie in adulthood and you have to adjust to its high-on-the-hog acting and broad-stroke storytelling. But adjust you will. The

New Republic

’s Otis Ferguson, the best American film critic of the day, called it “a picture so good in some ways that any but the most determined can see what fresh possibilities in the way of beauty and free movement lie in

this

new art of the screen.” Mahin and Fleming hit on a hyperbolic tone that’s scary, comical, and disrespectful of propriety—that’s what Ferguson meant when he wrote that they caught “the frank swagger of the story.”

Barrymore’s scowling, growling Billy petrifies the inn’s clientele with tales of seafaring men less “genteel” than himself who would slice and dice Spanish dons, ravish their women, and drain their feminine blue blood into punch. (The content is Stevenson, the words pure Mahin.) You know you’re in good hands when Dr. Livesey (Otto Kruger) enters the picture and, in a ringing line from Stevenson, vows to Billy that if he doesn’t stop brandishing his cutlass, he’ll “hang at the next assizes.” Kruger makes Dr. Livesey’s righteousness function as an invisible shield. And “Lionel Barrymore was just marvelous as Billy Bones,” Mahin remembered years later. “He had that shiny black beard; N. C. Wyeth had drawn color pictures of those characters, and his face was like that, just shiny from the weather.”

Fleming swiftly sketches Black Dog (Charles McNaughton) and Pew (William V. Mong) and the other scoundrels who go after Bones’s sea chest as part of a rogues’ gallery that stretches to infinity, or hell. In a breathtaking and brutal variation on Pew’s death scene from the book (one of the good guys’ horses tramples him), Dr. Livesey crushes the sightless brigand

twice.

His carriage horses knock Pew down; then both sets of carriage wheels create ruts in his body. (On location, Fleming used an Oakland riding-academy manager as the coachman, after forcing the fellow to shave off his grandiose mustache.) At its fringes, this

Treasure Island

is a Halloween cartoon. The score, with its insidious theme song—“Fifteen men on the dead man’s chest / Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum!”—employs a pastiche chantey and occasional bouts of minstrelsy to form a not-so-silly symphony. There’s something Disney-like about the way Fleming coordinates the score with images of desperate men straight out of Wyeth illustrations—pockmarked, wart-laden pirates in billowing capes tramping up lonely seaside lanes under lowering skies. (Fleming was thinking of Wyeth when he promised a columnist an “exact picturization of the book.”) When Jim croons the dead-man’s-chest song as Billy Bones walks the hills outside the inn, dirty dealings float through the air. Fleming’s

Treasure Island

belongs to the realm of good bad dreams.

After Jim saves the treasure map from Black Dog’s crew and delivers it to Squire Trelawney (Nigel Bruce) with Dr. Livesey, the Squire

hastens

to outfit a ship for his treasure hunt. In Stevenson, the Squire falls “in talk with” Long John Silver on the Bristol dock and hires him as sea cook. Mahin sharpens the action. The introduction of the sea cook and Jim at Silver’s Spy-Glass Inn had been, in previous scripts, too “long,” noted Mahin, “and not at all pictorial. Instead, in the final scenario, we have Jim, a boy in transports of delight, rushing here and there on the ship during his first moments aboard. Boy-like, he kneels down to sight a cannon, and through the porthole he sees a man with one leg!”

In this exhilarating presentation of the movie’s extraordinary good-bad guy, Fleming’s camera swings with Hawkins’s point of view until it fixes on Silver (Wallace Beery), who soon accepts the job of sea cook and takes the Squire up on his offer to replace a vanished crew. (Beery signals the audience that Silver is behind the seamen’s disappearance.) When Long John approaches the Spy-Glass Inn with Jim, he buys a whistle for his young friend—then uses it to alert his mates. With comical rapidity, they cease brawling and assume mellow, amiable postures as Dandy Dawson (Charles Bennett) sings and strums his mandolin. It’s the kind of stunt-like transformation found in Roaring Twenties movies set in speakeasies. And it’s typical of the filmmakers’ drive to keep the story dynamic as well as fable-like. Dandy Dawson, a Mahin-Fleming invention, is a true “dandy” who loves fine lace and sings Robert Herrick’s “Gather Ye Rosebuds While Ye May” but keeps a dagger hidden in his tricornered hat. “I like pretty things,” he tells Jim ominously, after Long John introduces them, and notes that with their similar shoe size, they’re like “two sister craft.” Jim never gets close to this predatory figure again.

Long John and Jim, though, become fast friends, because Silver treats the boy as a peer. In his script notes Fleming remarks, “What would help make the kid and the audience like him, even though he does slit throats, is the way he explains to the kid the necessity of one pirate having to kill another, etc.—it’s just a matter of business, that’s all.” In a way, it reflects the child star’s relationship with his director. When giving interviews at the time, Cooper said, “One thing I hate is to be treated like a baby. Mr. Fleming didn’t try any of that stuff on me. He’s my pal.” (Fleming, for his part, called Cooper “a great kid,” able to discuss everything from “screen stories” to “the Chinese situation.”)

Because Mahin and Fleming respect Stevenson’s structure, their version plays faster than the half-hour-briefer (ninety-minute) Disney

adaptation

from 1950. Fleming’s team holds true to Stevenson’s charged tableaux technique—they recognize that the relative impact of each episode is a matter not of length or adrenaline but of intensity of feeling. (“There was a fine sequence of the ship getting under weigh,” Otis Ferguson wrote, “one of the most lovely I have seen.”) And they pick up on the mildest suggestions of suspense and wit. Just when you think there couldn’t be a more righteous gentleman than Dr. Livesey, along comes Captain Alexander Smollett (Lewis Stone), who orders the sailors’ blades “tipped” (or blunted) when he fears they know they’re on a treasure hunt. (It’s another Mahin-Fleming invention.) Smollett borders on the prescient during the sea voyage. But he flits with foolishness after Silver’s mutiny. Smollett, Livesey, and Trelawney, along with a few good men, abandon ship and defend themselves in an empty island stockade. The stalwart captain flies the British flag and won’t pull it down even though it presents the pirates with a target. He’s determined to create a spot of England—a true-to-the-book incident that plays today like a piece of satire.

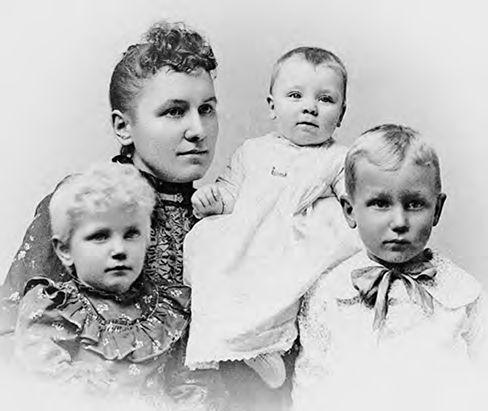

On her own: Eva Fleming with Victor, Arletta, and newborn Ruth, September 1893, Pomona, California.

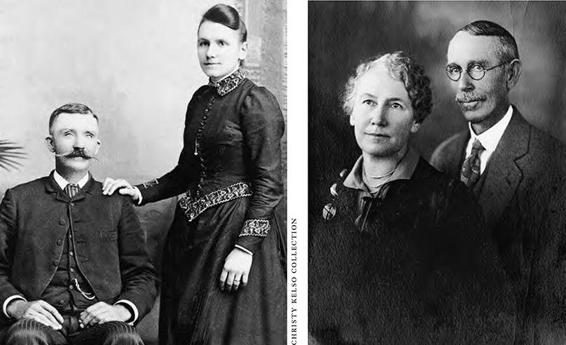

(left)

Starting out in California: Victor Fleming’s parents, Lon and Eva, in Pasadena, 1891.

(right)

Eva and her second husband, Sid Deacon, early 1920s.

(top)

Fleming in Santa Barbara, 1912.

(bottom)

Fleming is in the passenger seat of this camera car (year unknown), but his first goal in life was to become an automobile racer.

First lieutenant Victor Fleming of the Signal Corps mans a Bell & Howell camera while acting as Woodrow Wilson’s personal cameraman with the Presidential Peace Party, 1918.

Fleming filmed iconic images of President Woodrow Wilson in his top hat and kangaroo-pelt coat, touring the European capitals in triumph before the Versailles peace conference. Here Wilson is flanked by French prime minister Georges Clemenceau and British prime minister David Lloyd George.