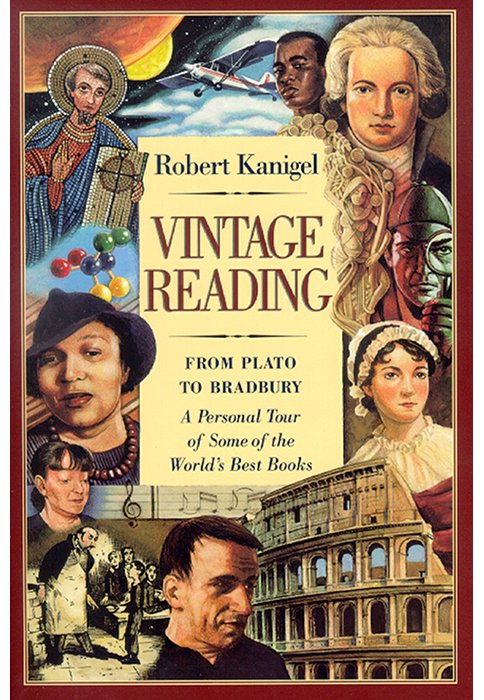

Vintage Reading

Authors: Robert Kanigel

READING

TO BRADBURY

A Personal Tour

of Some of the

World’s Best Book

Copyright 2010 by Robert Kanigel

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by electronic means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote passages in a review.

All the characters in this book are fictitious, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Published by Bancroft Press (“Books that enlighten”)

P.O. Box 65360, Baltimore, MD 21209

800-637-7377

410-764-1967 (fax)

www.bancroftpress.com

Printed in the United States of America

I. ON EVERYONE’S LIST OF LITERARY CLASSICS

As I Lay Dying

— William Faulkner

The Portrait of a Lady

— Henry James

Look Homeward, Angel

— Thomas Wolfe

Wuthering Heights

— Emily Bronte

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

— Lewis Carroll

Pride and Prejudice

— Jane Austen

A Passage to India

— E. M. Forster

Madame Bovary

— Gustave Flaubert

II. ON MANY A LIST FOR BURNING:

Heretics, Subversives, Demagogues

The Prince

— Niccolo Machiavelli

The Devil’s Dictionary

— Ambrose Bierce

Ten Days That Shook the World

— John Reed

III. BOOKS THAT SHAPED THE WESTERN WORLD

The Wealth of Nations

— Adam Smith

An Essay on the Principle of Population

— Thomas Malthus

The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

— Edward Gibbon

The Origin of Species

— Charles Darwin

The Federalist Papers

— Hamilton, Madison, Jay

The Annals of Imperial Rome

— Tacitus

The Peloponnesian War

— Thucydides

Democracy in America

— Alexis de Tocqueville

The Great Popularizers

Only Yesterday

— Frederick Lewis Allen

Microbe Hunters

— Paul de Kruif

Coming of Age in Samoa

— Margaret Mead

The Outermost House

— Henry Beston

The Amiable Baltimoreans

— Francis F. Beirne

What to Listen for in Music

— Aaron Copland

Gods, Graves, and Scholars

— C. W. Ceram

The Stress of Life

— Hans Selye

V. NOT BRAVE NEW WORLD, NOT ROBINSON CRUSOE:

Lesser Known Classics

A Journal of the Plague Year

— Daniel Defoe

The Doors of Perception

— Alduous Huxley

Elective Affinities

— John Wolfgang von Goethe

Homage to Catalonia

— George Orwell

Civilization and Its Discontents

— Sigmund Freud

Good Reads, Best Sellers

A Study in Scarlet

— Arthur Conan Doyle

The Song of Hiawatha

— H.W. Longfellow

The Rise of David Levinsky

— Abraham Cahan

Java Head

— Joseph Hergesheimer

Mr. Pottermack’s Oversight

— R. Austin Freeman

The Martian Chronicles

— Ray Bradbury

Gentleman’s Agreement

— Laura Z. Hobson

VII. “BUT I KNOW WHAT I LIKE...”

On Aesthetics and Style

The Ten Books of Architecture

— Vitruvius

The Live of the Most Eminent Italian Architects, Painters And Sculptors

— Giorgio Vasari

The Seven Lamps of Architecture

— John Ruskin

The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form

— Kenneth Clark

The Elements of Style

— Strunk and White

A Room of One’s Own

— Virginia Woolf

The American Language

— H.L. Mencken

The Little Prince

— Antoine de Saint Exupery

The Education of Henry Adams

— Henry Adams

Their Eyes Were Watching God

— Zora Neal Hurston

A Mathemetician’s Apology

— Godfrey H. Hardy

The Structure of Scientific Revolutions

— Thomas Kuhn

Holy and Human

The Razor’s Edge

— W. Somerset Maugham

The Seven Storey Mountain

— Thomas Merton

Death Be Not Proud

— John Gunther

The Bhagavad Gita

— Sanskrit poem

The Varieties of Religious Experience

— William James

Somehow, despite myself, I’d gotten stuck in the same stupid bind as everybody else. After more than a decade spent keyboard-pecking and deadline-squirming to the freelance writer’s quickstep, by the early 1980s I felt like every harried business executive, teacher, programmer, or parent— or, for that matter, like every drudge of a nine-to-fiver: I loved to read, yet wasn’t reading much. And what I did read was usually what I had to read. Oh, one time an assignment to profile Yiddish storyteller Isaac Bashevis Singer gave me the chance to read some of his strange, otherworldly creations. And a piece about city living sent me back to Jane Jacobs’ classic, The Life and Death of Great American Cities. But more often, I suffered the sad affliction of our age: Hopelessly caught up in the now, I had no time for those great old books of richness, subtlety, and originality I’d grown up hearing about, that were part of my cultural heritage, that I really wanted to read.

As it happens, my writing included the occasional book review, usually of books editors assigned to me. But, what if, the thought struck me one happy day, I picked what I’d review? And not books just then the object of some publicist’s intemperate pleadings, but classics of their kind, ones that had been around for fifty years, maybe, or five hundred.

I approached an editor at the Baltimore

Sun

. Would he be interested in reviews of old books? No, not too often, I reassured him. Not so often as to compete for editorial space with the latest war, fashion, or scandal. But maybe, say, once a month?

Thus was born “Vintage Reading,” a column which appeared first in the Baltimore

Sun

, then for much longer in the

Evening Sun

(now sadly folded into its bigger brother) and concurrently, for a while, in the

Los Angeles Times

, where it was called “ReReading.” For seven years, I took time out

from articles on bicycle racing, laser surgery, and the space shuttle to dip into Kipling and Thucydides, Flaubert and William James.

Vintage Reading

gave me the chance to read old books I wanted to read, then turn around and write about what reading them had been like. I am forever grateful for those years now. “Vintage Reading” was my own private liberal arts education (term papers and all). Except that rather than write to suit some professor’s pedagogical agenda, I was writing for readers of a daily newspaper— folks like myself who, however intelligent and professionally accomplished they might be, rarely had time for the books they didn’t have to read.

My credentials? Those only of a working writer, and of a long-time voracious reader and lover of books. The essays you find here are not the work of a scholar or academician. They are the work, and the pleasure, of a species of literary dilettante. They are middle-brow essays reflecting, I suppose, middle-brow sensibilities. They draw their inspiration from the friendly, more or less knowledgeable guide who brings to life the ruins of Pompeii or the glories of Chartres for visiting tourists.

A tour guide will not, of course, suit everyone. In particular, those of more academic stripe may come away hungry from these brief essays. They are, first of all, brief. But more, that very delight and sense of wonder many of us felt in college, say, as we met new authors, new books— an experience we associate, after all, with 18-year-olds—may seem to more refined palates simplistic or naive.

Still, I offer no apologies. My wish all along has been not to “protect” the great books behind daunting battlements, but to lower the drawbridge and welcome readers inside. If some find these essays less discriminating than they might prefer, I choose to see them as less standoffish— more open, accessible, welcoming.

Other readers may question my particular choices. Some, certainly, are predictable enough; who would omit Thomas Wolfe’s

Look Homeward, Angel

or Gibbon’s

Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

from any list of candidates for rereading, or first reading? But other choices may seem problematical or

perverse— such as works by the relatively unknown English detective story writer R. Austin Freeman, the Bavarian fantasist Gustav Meyrink, or the now forgotten American novelist Joseph Hergesheimer; or by frank popularizers like C. R. Ceram; or distinctly unliterary figures like, well, Adolf Hitler.