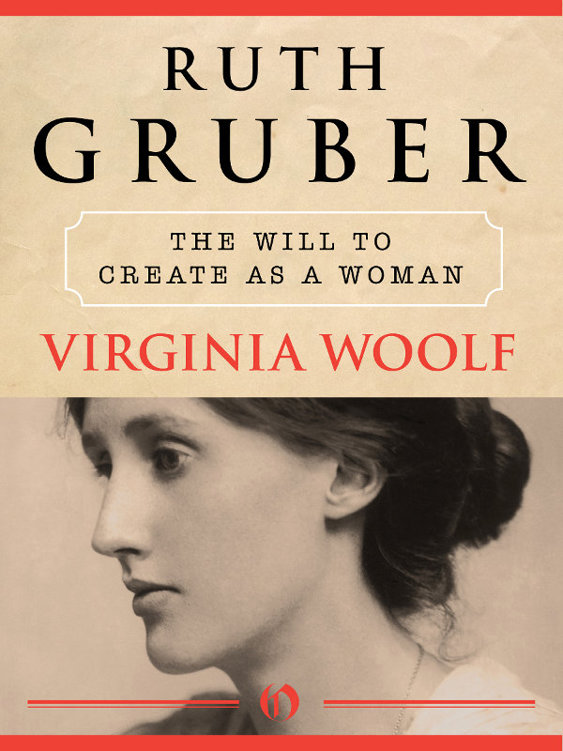

Virginia Woolf

Authors: Ruth Gruber

The Will to Create as a Woman

Ruth Gruber

Beginning on

page 55

, is a facsimile reproduction of the original 1935 edition of the work.

To my grandchildren Michael Evans and Lucy Evans

Joel Michaels and Lila Michaels:

Four votes of confidence in our future

Letter from Peggy Belsher of Hogarth Press to Ruth Gruber, Dec. 16, 1931

Letter of Recommendation from Barnes & Noble editor A. W. Littlefield, Feb. 25, 1933

Letter from Ruth Gruber to Virginia Woolf, May 8, 1935

Letter from M. West of Hogarth Press to Ruth Gruber, May 17, 1935

Letter from Ruth Gruber to M. West of Hogarth Press, May 28, 1935

Letter from Virginia Woolf to Ruth Gruber, June 21, 1935

Letter from Virginia Woolf to Ruth Gruber, Oct. 12, 1935

Letter from Ruth Gruber to Virginia Woolf, Dec. 27, 1935

Letter from Virginia Woolf to Ruth Gruber, Jan. 10, 1936

Promotional booklet for lecture bureau representing Dr. Ruth Gruber

Letter from Nigel Nicolson to Ai’da Lovell (for Ruth Gruber), Aug. 31, 1989

Letter from Ruth Gruber to Nigel Nicolson, Sept. 15, 1989

Letter from Nigel Nicolson to Ruth Gruber, Sept. 25, 1989

VIRGINIA WOOLF: A STUDY

by Ruth Gruber, originally published in1935

Chapter One—The Poet versus the Critic

Chapter Two—The Struggle for a Style

Chapter Three—Literary Influences: The Formation of a Style

Chapter Four—The Style Completed and The Thought Implied

Chapter Five—“The Waves”—the Rhythm of Conflicts

Chapter Six—The Will to Create as a Woman

MY HOURS WITH VIRGINIA WOOLF

MY HOURS WITH VIRGINIA WOOLF

O

NE MORNING IN THE

summer of 2004, my research assistant, Maressa Gershowitz, came running into the room where I was working.

“Look what I’ve found!” she shouted.

She held up three letters, sent to me by Virginia Woolf.

The letters were as fresh and unwrinkled as if Woolf had written them not in 1935 and 1936, but the day before.

“Where in heaven’s name did you find these letters?”

“You won’t believe this,” Maressa said. “They were in the back of one of your filing cabinets, behind a bunch of old tax returns.”

The past lit up. I shut my eyes, recalling how in 1931-32, as an American exchange student at the University of Cologne in Germany, I had written my doctoral thesis, called “Virginia Woolf: A Study.” Three years later, it was published as a paperback book in Leipzig under the same title. With apprehension, I had sent Woolf the book, and she had invited me to her London home for tea.

I recalled how on that day, the fifteenth day of October, 1935, I had walked up and down the narrow streets of Bloomsbury. I stared up at Virginia Woolf’s Georgian four-story house, which had a balcony overhanging the street.

Everything seemed magical to me. The rain, which had fallen all day, had stopped, and the air was as clean as if it had been scrubbed in a huge washing machine.

I rang the bell at 6

P.M.

at 52 Tavistock Square. A housekeeper in a black-and-white uniform opened the door, led me into a dark corridor and up a narrow staircase to the first floor. She tapped on a wooden door, and a man who introduced himself as Leonard Woolf stepped forward.

“Welcome,” he spoke warmly and shook my hand. He was painfully thin, with a long oval face, dark hooded eyes, black hair

laced with gray, and an air of sadness and suffering. He took me across a large parlor with sofas on each side, and motioned me to sit in an upholstered armchair close to Virginia.

She lay stretched out in front of a fireplace. The fire cast a glow over her carved straight nose, her expressive lips, her melancholy gray-green eyes. The beautiful Nicole Kidman, playing her in the film

The Hours

, did not need the built-up nose or the dowdy housewife clothes. Virginia Woof was elegant, a woman of grace and beauty.

She was a study in gray: short gray hair cut like a boy’s, a flowing ankle-length gray gown, gray shoes, and gray stockings. In her fingers, she held a long silver cigarette holder, through which she blew smoke into the parlor. There were three of us: Virginia, then fifty-three, reclining on a rug; her husband Leonard behind me, at the far end of the room but leaning forward as if he were hovering over her; and I, sitting inches away from her. I had come to sit at her feet. But now she was lying at mine.

The fire warmed me in front as I faced her, but my back was chilled. I pulled my jacket tight around me and sat in silence, too overawed to speak.

“I looked into the study you wrote about me,” she said. “Quite scholarly.”

Was she praising me? I could scarcely believe it. I did not know whether to thank her or remain silent. I chose silence.

She took a long draft of smoke and said, “I understand from my secretary that you are writing a book on women under fascism, communism, and democracy.”

I murmured, “Yes.”

“And you want to interview me for your book. I don’t know how I can help you. I don’t understand a thing about politics. I never worked a day in my life.”

I wondered how she considered that it was not work to write groundbreaking novels, brilliant essays, and book reviews, and why she would demean her knowledge of politics. Her books were full of politics; her friends in the Bloomsbury crowd were energetic political thinkers—Lytton Strachey, the poet and historian who had wanted to marry her but whom she rejected; John Maynard Keynes, the economist; Roger Fry, the painter whose biography Virginia later wrote; and T. S. Eliot, the poet whose lines like “In

the room the women come and go, talking of Michelangelo” often sang in my head.

“I understand,” she said, “that you have been traveling. Where have you been?”

“Germany, Poland, Russia, and the Soviet Arctic.”

“The Soviet Arctic!” Leonard called out.

I turned to look at him.

“I didn’t think,” he said, hunching closer, “that the Russians allowed anyone to go up there.”

“They said I was the first journalist.”

“And you were writing for whom?” he asked.

“The

New York Herald Tribune

.”

“How old are you?”

“Twenty-four.”

“And how old were you when you wrote your essay on Virginia?”

“Twenty.”

Virginia seemed not to be listening, drifting off, when her housekeeper Lotte entered with a tray of teacups. She handed me one, but I put it on a small table next to me. I was afraid my hands would tremble and I would drop the cup. Virginia sipped her tea gracefully and began to speak again.

“We were just in your Germany,” she said.

Why did she call it

my

Germany? True, the thesis had been published as a trade paperback by the Tauchnitz Press in Leipzig. The publishing house, then 100 years old, was famous for printing the books of English and American authors such as Jane Austen, Charles Dickens, Mark Twain, and Virginia Woolf, all for tourists who could not read German and wanted to read a good book while traveling. To be sure, I had sent her my first letter in 1931 while I was a student at Cologne University. But I had sent the published book from my home in Brooklyn in 1935. She had sent her answer to me in Brooklyn, and I had spoken with a New York accent.

“We were driving through Bonn, on holiday,” she said. “Our car was stopped to let Hitler and his entourage pass.”

From her diary of April 2, 1935, I later read her impressions as she watched the Nazi convoy:

Hitler, very impressive, very frightening. … No ideals except equality, superiority, force, possessions.

And the passive heavy slaves behind him, and he a great mould coming down the brown jelly.

1

In her parlor, puffing her cigarette, Virginia Woolf shook her head, still talking of Germany.

“Madness, that country. Madness.”

I felt I could talk comfortably about Germany; I had lived there from 1931 to 1932.

“When I was an exchange student in Cologne,” I said, aware that Leonard was moving his chair closer to me, “I went to a Hitler rally held in a

Messehalle

, a huge hall near the Rhine. The family I lived with was terrified that I might be arrested, but I was determined to find out what that madman was really like.

“There were guards and soldiers everywhere, but no one stopped me and I entered the hall with trepidation. I found a seat in a half-filled balcony near the stage. A brass band struck up marching music as, within minutes, the hall filled up with an army of stormtroopers in brown uniforms and heavy black boots, marching and waving flags with swastikas.”

I paused. Had I talked too much?

Leonard moved his chair closer, as Virginia took the cigarette holder out of her mouth. I went on:

“The crowd went wild when Hitler entered and goose-stepped to the podium, followed by his entourage. The audience shouted, screamed, some applauded, others wiped their eyes in rapture. My heart was beating so loud, I thought one of those SS men would surely hear and maybe throw me out. But no one approached me.

“The moment Hitler raised his right hand in salute, the band stopped playing, the stormtroopers stopped marching, the flags stopped waving. Hitler’s worshippers stood frozen.”

Leonard nodded, as if to encourage me to go on. Virginia had still not resumed smoking.

“Hitler,” I said, “was ranting against the Weimar Republic, ranting against America, and mostly against Jews. It was a

hysterical voice that seemed to come not from his throat, but from his bowels. Terrifying.”

“He

has

a terrifying voice,” Virginia agreed. “There is such horror in the world.”

I took up courage to say more.