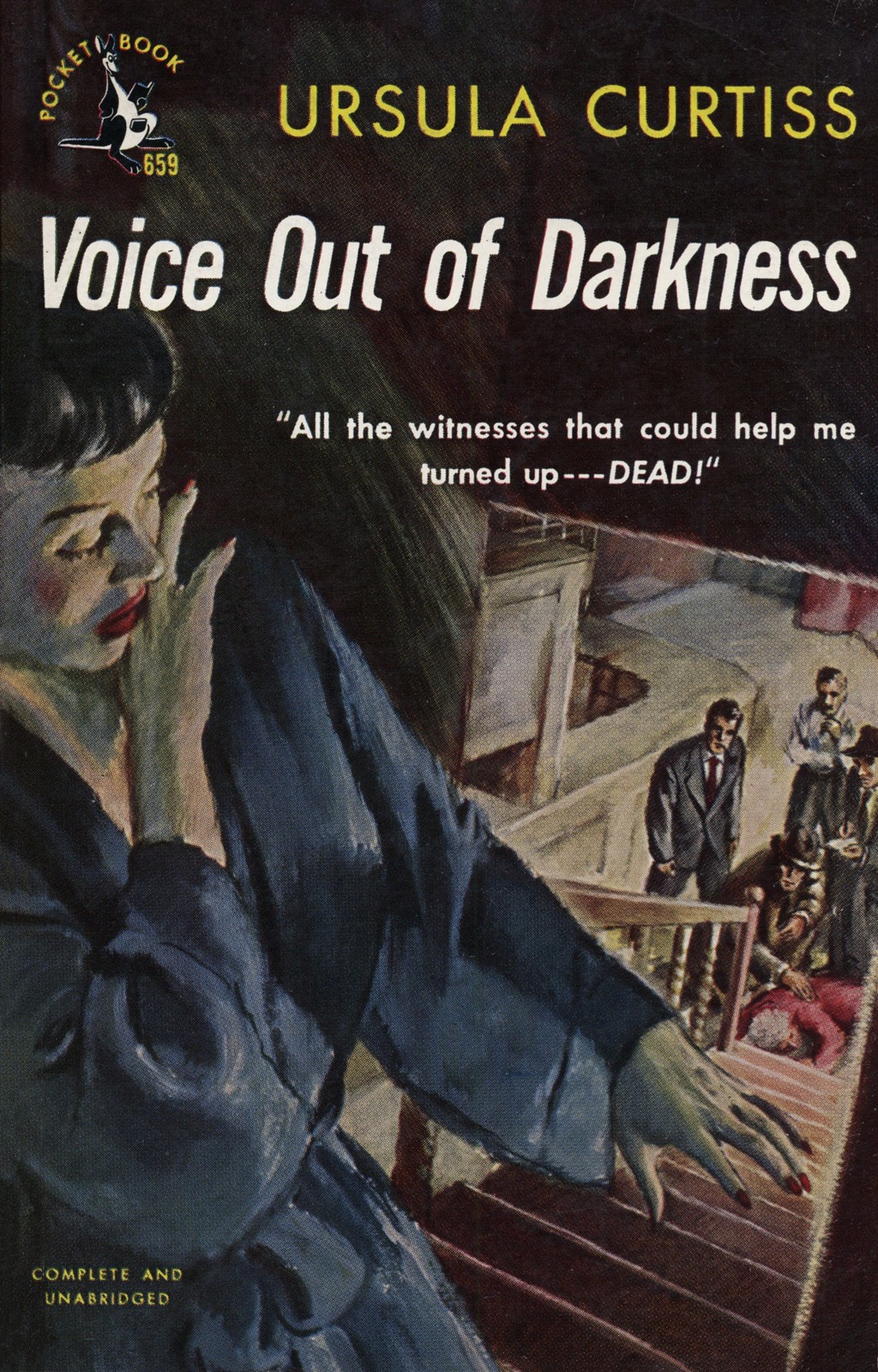

Voice Out of Darkness

Ursula Curtiss makes her entrance into the Pocket Book list with the first-rate mystery thriller, Voice Out of Darkness. This novel won the $1,000 Red Badge Prize Mystery contest. With the award went some of the finest reviews ever accorded a first mystery. The Saturday Review of Literature said, “Suspenseful, credible, and a competently plotted tale. Worth its ‘Red Badge’ prize.”

The Printing History of

Voice Out of Darkness

Dodd, Mead edition published October, 1948

1st

printing ……………… September,

1948

Detective Book Club edition published December, 1948

1st

printing ……………… December,

1948

Pocket Book

edition published March, 1950

1st

printing ………………. February,

1950

This Pocket Book includes every word con-

tained in the original, higher-priced edition. It

is printed from brand-new plates made

from completely reset, large, clear, easy-to-read type

Trade-mark Registered in U. S. Patent Office, and

in foreign countries including Great Britain and Canada.

POCKET BOOK editions are published only by Pocket Books, Inc.,

Pocket Books [G.B]

Ltd., and Pocket Books of Canada, Ltd.

Printed in the U.S.A.

Copyright, 1948, by Ursula R. Curtiss

This

Pocket Book

edition is published by arrangement with Dodd, Mead & Company

The characters and situations in this book are wholly fictional and imaginative; they do not portray, and are not intended to portray, any actual persons or parties.

Katy Meredith,

who has been receiving, in her New York apartment, unpleasant reminders of a day thirteen years ago in the little town of Fenwick

Monica Meredith,

Katy’s foster sister, whose pudgy presence lingers on after her death.. i

Michael Blythe,

commercial artist whom Katy loves

Cassie Poole,

suddenly a stranger to Katy, despite their shared experience thirteen years ago

Jeremy Taylor,

Cassie’s fiancé, a remote young man with a cynical eyebrow

Lieutenant Hooper,

who looks like a demure suburban commuter—except for his eyes

Pauline Trent,

eccentric tenant of the old Meredith house

Arnold Poole

, who left his wife to live with an enigmatic sculptress

Francesca Poole,

Cassie’s glamorous mother—a not-so-merry widow

Mr. Lasky,

innkeeper

of Fenwick Inn

Alice Whiddy,

who earned her reputation for sharp eyes and ears

Ilse Petersen,

cold in manner and mien

Mr. Farrow,

a florist

Harvey Pickering,

Francesca Poole’s current escort—a lawyer of ultra-immaculate manners and reputation

Frank Abbot,

Fenwick’s able chief of police

Sergeant Gilfoyle,

his astute assistant

Mrs. Galbraith-Carlotti,

Ilse Petersen’s stolid and disapproving aunt

Katy

got the third letter early in December, after a snowy dusk had turned into windy darkness and she was back at the little apartment on Tenth Street.

She had left her office later than usual, and had stopped on the way home for lamb chops and the makings of a salad because Michael had, quite unexpectedly, asked himself to dinner. “I want to find out if you can cook,” he had said unsmilingly, “for reasons which you can never possibly guess.” So Katy, who had looked calmly away and said, “You can come tomorrow night if you’d like,” was feeling expectant and a little giddy when the creaking elevator let her out on the fourth floor at about six-thirty.

The letter lay there on the mat, in the familiar square white envelope with “Miss Katherine Meredith, Apt. 4A” written neatly on the front. No stamp, no postmark. Katy stood looking down at it for a moment, tall and suddenly stiff, snow on her shoulders and her smooth brown hair. All at once the pleasant giddiness had gone away, and she felt flat and cold and angry. Why tonight, when she had been looking forward to a martini and dinner with Michael? Why at all, when Monica, who had slipped and plunged through the treacherous ice, had been dead for thirteen years?

In the bright little kitchen, with the chops and salad things tumbled on the table, Katy opened the letter. It was a single sheet of paper, the kind you could buy at any drug store or stationery shop. On it was scrawled, in firm black ink, “You pushed her.”

The kitchen clock ticked noisily in the silence; the lettuce came crackling out of its paper bag and rolled across the table. Katy folded the letter and put it back in its envelope and switched on the light in the tiny dining alcove. In a bookcase under the window, sandwiched in between two books on the middle shelf, were two other square white envelopes. Katy added the third and stood looking down into the quiet street. It had reached the point where she would have to tell Michael. Michael would know what to do. Meanwhile there was the table to set, and a bath to take, and that dreadful inner trembling to stop.

The first two didn’t take long. Pulling biscuit-colored wool over her head, fastening a narrow gold belt at the waist, Katy forced her mind away from the letters and thought about Michael Blythe, whom she had seen desultorily ever since the summer and somewhat less desultorily for the past three weeks. She didn’t, actually, know a great deal about him. She knew that his parents lived in Chicago, that he was in his early thirties, that he was currently working as an artist for a small company that specialized in advertising presentations. That, in his spare time, he did free-lance magazine illustration which, he said, was a nice change from drawing graphs showing a ratio of three and one-half men to every fir tree in the country. (“Gibberish,” Katy had said, laughing. “Not a bit,” said Michael. “You’d be surprised how it is with fir trees.”)

But who hates me like that, thought Katy, who’s been brooding about Monica and the little pond for thirteen years?

She brushed her hair and put on lipstick and had looked at the clock twice by the time the doorbell rang. She’d wait, she’d make herself wait until after dinner before she mentioned the letters. Because then, inevitably, it would all come back, sharp and clear and ugly, and there’d be no point to the martinis or the warm glow of the alcove.

Michael had brought champagne. When Katy opened the door, he was cradling it in his arms, looking at her out of very blue eyes. “Don’t say a word,” he said. “Commission. Very small, but calling for champagne.” He followed Katy into the kitchen. “Anything I can do in here?”

“You might make a martini,” Katy said, “while I attend to the salad dressing. I’m glad about the commission—what’s it for?”

While Michael told her, and later when she tucked herself into a corner of the couch and he poured cocktails and toasted her gravely, Katy thought detachedly how perfect this ought to have been. Snow coming down beyond the black shining windows framed in looped-back white organdy, inside, warmth and lamplight and the table in the alcove, and Michael sitting in the chair beside the window, less casual tonight than he’d ever been. And, hidden in the little bookcase, three innocent-looking white envelopes, three incredibly malevolent messages.

“—met a friend of yours today,” Michael was saying.

Katy wrenched her mind and her eyes away from the middle shelf of the dining-room bookcase and looked up inquiringly.

“Cassie Poole,” Michael said. “The one who went to school with you in Connecticut. What’s the matter? ”

Cassie was there, at the little pond.

“Nothing,” Katy said carefully. “I haven’t seen Cassie in years. Is she living in New York, did she say?”

Michael shook his head. “I gathered she was still in Fenwick. Jones and I were at the Biltmore softening up a client, and she came by and stopped at the table for a minute. Considering we’d only met once—at that cocktail party I told you about, remember?—I was surprised that she knew me. Our client, I might add, was thoroughly dazzled. I think he’d have pinched her if the waiter hadn’t been in the way.”

Katy smiled absently. “Cassie’s quite a girl. Oddly enough, she’s also very nice. I suppose she’d been shopping, if she was alone.”

“She wasn’t,” Michael said quickly. “Just as our client was about to leave his wife and children a man came along, and she said so nice to have seen you again and give my love to Katy and went off with him.”

“Oh,” Katy said.

Michael looked at her and sighed and looked at the ceiling. “Well, I didn’t quite catch the color of his eyes,” he said. “He was tall, very fair, and in an extremely bad temper. It seems to me there was something funny about one of his eyebrows. This is your FBI.”

“He was hit by a golf club,” Katy said abstractedly, “that is, if it was Jeremy Taylor.” She twirled her glass, not seeing the spinning reflections. “Jeremy’s from Fenwick, too. Funny.”

“Is it?” Michael said. He was looking at her curiously, frowning a little.

Not now, not till later, Katy thought warningly. She jumped up from the couch. “I’ll put on the chops.”

“Good,” Michael said, picking up her glass. “I’ll mix another martini.”

It was almost ten when dinner was through and they sat over a second cup of coffee in the living room. Katy had very nearly done a good job of being gay. Fenwick, the years she had spent there, the people, the scarring memory, had come rushing back like a wall of water with the mention of Cassie Poole and Jeremy Taylor. Instead of the shabby, charming room in the Village apartment that had been her home for four years, there was an icy gray day in Fenwick, Connecticut, so cold and still that their voices and their breath crystallized on the air. There was the little pond, laced and feathered with white where their skates had cut it, and the dark smudged ring of pines against an asphalt sky. Katy, chilled and tired and twelve years old, was saying, “Come on, Monica…”

Michael stirred restlessly. He looked at his watch. “If you don’t mind the snow, we could make that French movie you wanted to see.”

“Would you mind if we didn’t?” Katy said. Now that the time had come to tell Michael about the letters, she felt ridiculously nervous. She left the couch and went into the dining room and came back with the three white envelopes. “I’ve been finding these outside my door,” she said simply, and put them into his hands.

She turned her back deliberately and was very elaborate with a cigarette and a match while Michael read the few brief vicious phrases. She heard the letters being folded and replaced and then there was a small waiting silence; into it Michael said tentatively, trying for lightness, “You correspond with some very unpleasant people, Katy.”

“Don’t I,” said Katy. She took a few aimless steps toward the dining room and turned back again. “You see, it’s about Monica.”

“Monica,” Michael said gently, “is news to me. Don’t you think you’d better sit down and tell me what this is all about? If you want to, that is.”

Katy sat down. “I’m sorry. I’m nervous, and I’m fluttering around like a fool. Monica was my foster-sister.” She smiled across at Michael, feeling calmer. “You can stop me at any point and make a drink, if you like.”

“I’ll let you know. Go on.”

“As I’d told you, I was adopted,” Katy said. “The Merediths—I called them Aunt Belinda and Uncle John—married rather late, and I think Monica came as quite a jolt to them both. Anyway, when she was three, they adopted me, partly so Monica would have someone to grow up with and partly because Aunt Belinda had theories about only children. I was going on three too.”