Voice Out of Darkness (24 page)

“No. Not really,” Jeremy said abruptly, and moved toward the doorway.

“Jeremy,” Katy said delicately, and he turned. “You warned me away from Fenwick. You kept saying I’d better go back to New York with Michael—why?” Jeremy looked at her, his greenish eyes calm and very steady. He said, “Because I was engaged to be married, and so were you. I couldn’t sit in a car with you, or be in a room with you, without wanting to lose my head. I thought that maybe if you went away, that would be an end to it.” He looked at her for a moment longer and said gently, “Goodnight, Katy.”

Katy didn’t speak. She went to the door with him and saw his hand on the knob and was astonished to hear her own voice saying, “So now you’re going away.” How could you be twelve again so suddenly, smotheringly conscious of every breath you drew? Because Jeremy had turned again and was looking at her, very differently, with something leaping in his face. He put out a hand and touched her hair, gently and tentatively, and said, “Going away? No farther than the nearest hotel. Will I see you tomorrow, Katy?”

“Yes. Tomorrow,” Katy said, and closed the door slowly behind him and was no longer alone.

FIN

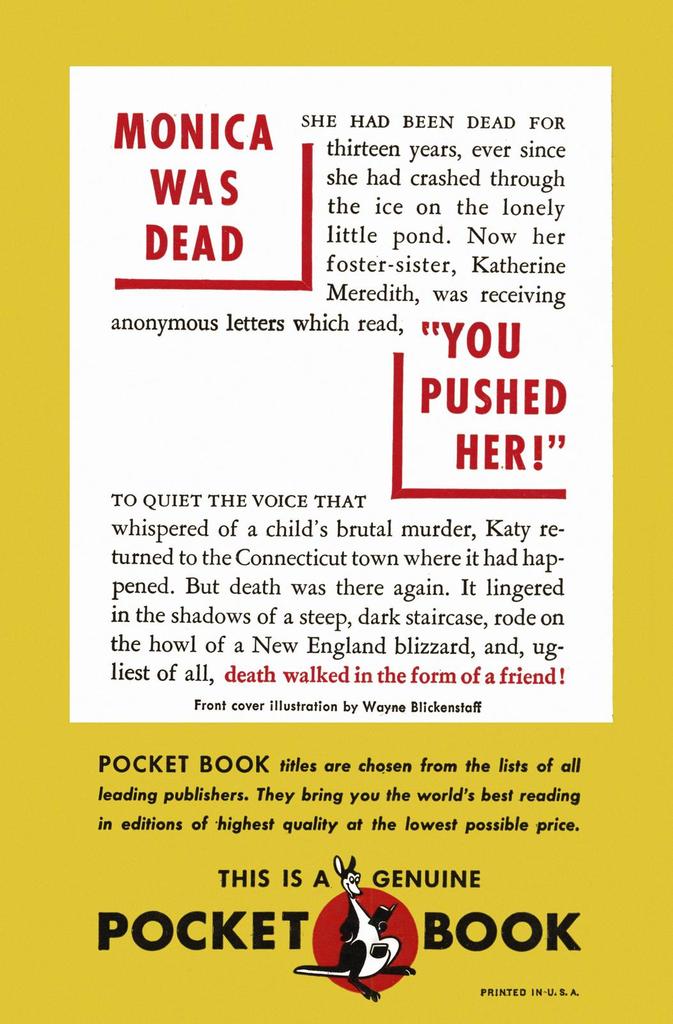

Ursula Curtiss (1923-1984) was the daughter of Golden Age mystery writer and police procedural pioneer Helen Reilly. She came to writing fiction late in her life unlike her prolific mother, but seemed to have inherited her mother’s talent for tight plotting, lively and original characters, and well rendered settings. She surpassed in mother with an enviable talent not too easily mastered in crime fiction. Curtiss’ mastery in nearly all her books is her skill in creating mounting dread and terror.

- Voice Out of Darkness (1948)

- The Second Sickle (1950)

- The Noonday Devil (1951)

- The Iron Cobweb (1953)

- The Deadly Climate (1954)

- Widow’s Web (1956)

- The Stairway (1957)

- The Face of the Tiger (1958)

- So Dies the Dreamer (1960)

- Hours to Kill (1961)

- The Forbidden Garden (aka Whatever Happened to Aunt Alice?) (1962)

- The Wasp (1963)

- Out of the Dark (aka Child’s Play) (1964)

- Danger Hospital Zone (1966)

- Don’t Open the Door (1968)

- Letter of Intent (1971)

- The Birthday Gift (aka Dig a Little Deeper) (1975)

- In Cold Pursuit (1977)

- The Menace Within (1979)

- The Poisoned Orchard (1980)

- Dog in the Manger (aka Graveyard Shift) (1982)

- Death of a Crow (1983)

`