Read Voices From S-21: Terror and History in Pol Pot's Secret Prison Online

Authors: David P. Chandler

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Political, #Political Science, #Human Rights

Voices From S-21: Terror and History in Pol Pot's Secret Prison (34 page)

BOOK: Voices From S-21: Terror and History in Pol Pot's Secret Prison

2.17Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

ads

Group of guards at S-21 (

1977

). Him Huy is fourth from right. Photo Archive Group.

Him Huy in

1995

. Photo by Chris Riley, Photo Archive Group.Koy Thuon (alias Khuon), high-ranking DK cadre imprisoned in

1977

. Photo Archive Group.

Bedroom on ground floor of S-21, reserved for important prisoners. Photo Archive Group.

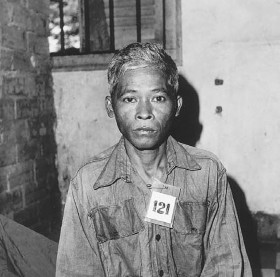

Unidentified prisoner in front of wooden cell, S-21. Photo Archive Group.

Mug shot and postmortem photographs of Voeuk Peach. Photo Archive Group.

Prisoner

259

(

1977

?) showing the room where unimportant captives were held en masse. Photo Archive Group.

Chan Kim Srun (alias Saang), the wife of DK foreign ministry official, and her baby. Photo Archive Group.

Overleaf:

Skulls of S-21 prisoners, Choeung Ek. Photograph by Kelvin Rowley.

Nhem En at the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum,

1997

. En was the first Khmer Rouge photographer to take mug shots of S-21 prisoners. Photograph by Douglas Niven.dated 4 April 1976 (uncatalogued item in the DC–Cam archive), reported no unrest in the Zone. CMR 12.25, Cho Chan (alias Sreng), parroting the Party line, suggested in March 1977 that the explosion reflected “the angry fury of American imperialism, which had never [before] lost to any country in the world.” Steve Heder (personal communication) has suggested that Thai military aircraft might well have been involved.

- Writing such a history was my original goal when I started working on the S-21 archive in 1994. Because of the nature of the S-21 texts, the task soon became impossible. See chapter 1, n. 2, for a list of historical syntheses of the Khmer Rouge period. Only Becker’s

When the War Was Over

makes extended use of the S-21 archive. - On using the confession texts as evidence, see Heder, “Khmer Rouge Opposition to Pol Pot”: “In principle, you have to assume that every word may either be a falsehood forced upon a terrified writer . . . or a falsehood concocted by the writer to save his or her life by denying what is true. . . . And yet long before one is through the first thousand pages, it becomes obvious to the reader that some things are undoubtedly true” (11). Heder suggests (private communication) that the “truest” parts of confessions are often those dealing with events prior to 1970.

- See, for example, my own faulty assessment in Chandler, Kiernan, and Boua,

Pol Pot Plans the Future,

xviii. - Published translations of DK documents into English include Becker,

When the War Was Over

(appendixes); Carney,

Communist Party Power in Kampuchea,

251–314; and Chandler, Kiernan, and Boua,

Pol Pot Plans the Future.

Heder has translated several key articles from

Tung Padevat

and

Revolutionary Youth

and over a thousand pages of confessions from S-21. None of these invaluable translations, aside from some passages from confessions in the appendixes to Becker’s book, has yet been published in full. With Heder’s permission, I have used several of them in this book. - In 1995–1997, additional DK documents were turned over to the CGP and DC–Cam by the Cambodian Ministry of the Interior and other sources. On DK archives in Vietnam, see Engelbert and Goscha,

Falling out of Touch,

xv–xvii. Cooperatives kept extensive records in DK, which have for the most part disappeared (Steve Heder, personal communication). Additional archives from the DK period were assembled in the 1980s by the historical commission of the People’s Revolutionary Party of Kampuchea (PRPK). These are known to have survived but are not accessible to outsiders. I am grateful to Richard Arant for this information. - Heder, conversations with the author, 1995–1996.

- See Central Committee of the CPSU,

History of the Communist Party.

According to author’s interview with Pierre Brocheux, French Communist Party members in the early 1950s, who would have included Pol Pot, Son Sen, and Ieng Sary, diligently studied this text. On its popularity at Yan’an during the 1940s, see Apter and Saich,

Revolutionary Discourse,

275. On CPK notions of history, see Chandler, “Seeing Red,” and the Party histories translated in Jackson,

Cambodia 1975–1978,

251–68, and in Chandler, Kiernan, and Boua,

Pol Pot Plans the Future,

213–26. - Engels to Marx, 4 September 1870; see also also Juan Corradi, Patricia Weiss Fagen, and Manuel Antonio Garreton, “Fear: A Cultural and Political Construct,” in Corradi, Fagen, et al., eds.,

Fear at the Edge,

1–10. - D. Spence,

Narrative Truth and Historical Truth,

and Malcolm,

ThePurloined Clinic,

31–47, a review of Spence’s book. See also Ignatieff,

The Warrior’s Honor,

98–99, which speaks of “narratives of explanation” and “moral narratives” that shape our views and color our behavior. In a recent book David Apter compares what he commends as “historians’ history” with “‘fictive history,’ the stories and myths people use to ‘order’ the events of their lives and cir-cumstances” (

The Legitimation of Violence,

20). - “Decisions of the Central Committee on a Variety of Questions,” in Chandler, Kiernan, and Boua,

Pol Pot Plans the Future,

1–9. - See uncatalogued item in DC–Cam archive, dated 12 April 1976. Duch’s

note is attached to a brief, unmicrofilmed confession by Yim Sombat, a soldier in Division 170, who admitted throwing the grenade, egged on by fellow soldiers. His company commander, Sok Chhan (CMR 145.13), had confessed earlier to ordering the “attack.” Duch’s covering note on Yim Sombat’s confession mentions a two-sided tape recording, one side devoted to questions and the other to Sombat’s replies, and observes that Sombat “lost consciousness” at several points in the course of his interrogation.

- For a list of Division 170 prisoners, see CMR 103.2, “Division 170.” Exactly what happened on 2 April remains unclear. Scattered evidence suggests the existence of antigovernment feeling centered in the military in the capital and extending into the Eastern Zone. See Heder interviews, in which a former DK cadre said that “around April 1976 artillery was set up around Chbar Ampeou to bombard Pol Pot’s headquarters. . . . The Center found out about the plan and suppressed it before it could be carried out” (45). Again, it is unclear whether the cadre was drawing on his own memories or on what he was told at Party meetings after the event.

- Chan Chakrei’s 849-page confession is CMR 11.7. On his career, see Heder interviews, 44 ff.; Burgler,

Eyes of the Pineapple,

108–9; and Kiernan,

How Pol Pot Came to Power,

257. According to Heder (personal communication, drawing on interviews), Chan Chakrei had been hired by Sihanouk’s police to infiltrate the CPK but had instead drawn some of his handlers into the CPK. Quinn, “The Pattern and Scope of Violence,” 195 ff., quotes Cambodian refugees on Chakrei, who may have been told by cadres about Chakrei’s alleged offenses, using information drawn from his confession. See also Chandler, Kiernan, and Boua,

Pol Pot Plans the Future,

in which Hu Nim confesses that Chan Chakrei had told him, “I know how to disguise myself misleadingly. Whenever I went to a new place I would adopt a new name. No one knows my real history” (299). Kampuchea Démocratique,

Livre noir,

states that Chakrei “intended to murder the leaders of the CPK.” - I am grateful to Richard Arant for pointing out this passage to me and for providing this deft translation. On the timing of Chhouk’s arrest, see CMR 123.2, Phuong, November 1978: “Upon Phim’s return from abroad, he arrested Chhouk and sent him to the Organization in accordance with the dossier [from] the Organization.”

- On acclimatizing cadres to the Plan, see Chandler, Kiernan, and Boua,

Pol Pot Plans the Future,

9–35, a relatively upbeat June 1976 speech by a “party spokesman” in the Western Zone. See also CMR 50.14, Keo Meas; CMR 80.36, Ney Saran; CMR 13.28, Chey Suon. A fourth veteran, Keo Moni (Number XVI, CMR 49.15) was a “Hanoi Khmer” arrested in late October 1976. Chhouk’s deputy in Sector 24, Pot Oun (CMR 106.28), was not arrested until mid-1977. Two other senior fi linked to the anti-French resistance were Sao Phim and Nhem Ros, the secretaries of the East and Northwest Zones, who in April 1976 became first and second vice presidents of the DK National Presidium under Khieu Samphan. Their names began cropping up in confessions in mid-1976, but Nhem Ros was not arrested until 1978, and Sao Phim committed suicide in May 1978. Meas Mon, arrested after Sao Phim’s suicide, suggested in his confession that a full-scale conspiracy was under way in the east in 1976. The Party Center’s tardiness in acting on such a conspiracy suggests that it did not exist, that the Center was not confident enough to attack high-ranking cadres in the zone, or that Keo Samnang was backdating the Cen-ter’s 1978 suspicions of the east to 1976, to enhance its record of clairvoyance. All three possibilities probably were at work. - On the foundation of the WPK, see Kiernan,

How Pol Pot Came to Power,

190–93, and Chandler,

Brother Number One,

79. The notion that the WPK was a “rival” party is a clear case of the Center and S-21 fabricating or inducing “evidence” consonant with its altered versions of history and the Party Center’s habit of giving its opponents multiple labels. Interestingly, many prisoners who confessed to membership in the WPK gave it the three-man cell structure of the CPK, often “remembering” only two other members. Attacks on the “rival party” persisted for the lifetime of DK. On 25 July 1978, for example, the Tuy-Pon notebook carried the notation: “Our task: locate the leading apparatus

(kbal masin)

of the Kampuchean Workers’ Party (Vietnamese slave).” By then, Sao Phim, long suspected of filling this position, had already killed himself. - CMR 124.17, trans. Steve Heder. CMR 71.10, Meas Mon, for example, confessed that the WPK had been established in 1976 and had five members. Senior cadres often confessed to crimes and memberships that they could well have learned about in study sessions before they were arrested. See also “The Last Plan,” 313: “The enemies admitted many names, such as the new CP, the CP of Revolutionary Cambodia, the Workers’ Party, the People’s Party, the Socialist Party.” Once the prisoners had become traitors, by being arrested, the names of the “parties” they had belonged to were of marginal interest— although the admission of membership was crucial.

- The speech and the plan itself are translated in Chandler, Kiernan, and Boua,

Pol Pot Plans the Future,

119–63 and 36–118. Willmott, “Analytical Errors,” analyzes the conceptual framework of the Four-Year Plan and other CPK initiatives. The announcement of the Party’s existence was delayed until September 1977, and the Four-Year Plan was never formally launched. - Heder interviews, 61.

- At the 18 September ceremonies, Pol Pot delivered two eulogies to the Chinese leader (FBIS, 29 September 1976). For Sun Hao’s remarks, see FBIS, 21

September 1978. A dutiful DK attack on Deng Xiao Ping, broadcast by Phnom Penh Radio on 1 October, was soon eclipsed by the arrest of the Gang of Four, and on 22 October 1976, after Pol Pot had publicly resumed work as DK’s prime minister, he sent a telegram to Beijing condemning the Gang of Four. According to a former Chinese diplomat, the key personnel of the Chinese Embassy in Phnom Penh, all Cambodia experts, remained unchanged (author’s interview).

- On the resignation, FBIS, 30 September 1976. On Ta Mok’s and Nuon Chea’s reactions to it, Nate Thayer (personal communication). The fact that Ieng Sary recalled the incident clearly in his interview with Steve Heder suggests that the “resignation” may have had something to do with foreign affairs; perhaps, for example, it was done so that Pol Pot could avoid meeting an unwelcome foreign guest. No corroboration for such a hypothesis is available, however.

BOOK: Voices From S-21: Terror and History in Pol Pot's Secret Prison

2.17Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

ads

Other books

Maybe Fate: A Novel (New Adult Paranormal Romance) by Brint, Cynthia

Invasion by Mary E Palmerin, Poppet

The Unkindest Cut by Gerald Hammond

The Winter Long by Seanan McGuire

4 Blood Pact by Tanya Huff

Bear Prince: Shifter Paranormal Romance (Royal Bears Book 1) by Emma Alisyn, Danae Ashe

Dirk Gently's Holistic Detective Agency by Douglas Adams

The Mystic Rose by Stephen R. Lawhead

Sudden Pleasures by Bertrice Small

Live to Tell by G. L. Watt