Walking to Hollywood: Memories of Before the Fall (33 page)

Read Walking to Hollywood: Memories of Before the Fall Online

Authors: Will Self

*

It was anomalous that no one seemed to be played by anyone else at this gathering, although when I came to reflect on it later there was one exception – Ellen DeGeneres as Stevie Rosenbloom. I cannot account for the veridical nature of the events recounted below, except to suggest that I was thrown by the contrast with the last Hollywood party I’d been to, almost a decade before, at Carrie Fisher’s house. That was a true ‘night of a thousand stars’ – or at least, I think it was. At one point I found myself in the line-up for the chicken gumbo with Rod Stewart, Geena Davis and the entire featured cast of Blake Edwards’s

The Party

(excluding, of course, Peter Sellers); then later on I asked the crown of Jack Nicholson’s head if: ‘You get out much?’

Being in one space – albeit the sort of hypertrophied living room-cumterrace mandatory for second-generation movie royalty – with that much notoriety could’ve been the beginning of the Syndrome, because, while these faces were as familiar to me as my own (and, in many cases, having examined the play of their features for many hours, far more so), I had the disagreeable sensation that they were not who the world claimed them to be, but rather a bunch of saddo impersonators, scooped up off the sidewalk outside Grauman’s and taken on by Fisher as a job lot to amuse persons unknown who were sitting hidden behind two-way mirrors, snorting cocaine and laughing hysterically.

The Virgil of Laurel Canyon

It must have been a hell of night, because when I awoke – tucked as savagely into my bed as I had been by the disapproving nurse at Heath Hospital thirty years before – I found I’d had breast implants done. And not just any breast implants Laura Harring’s. At least, I fantasized that they might be Laura Harring’s breast implants, because when I examined them in the full-length mirror on the bathroom door they had a combination of inelasticity and prominence that reminded me of the improbability of her chest – relative to the slimness of her back – when Harring and Naomi Watts took off their tops to fake love in David Lynch’s

Mulholland Drive

*

(2001).

I wondered whether implying that anyone might have had breast implants was libellous – but the alternative – that these were Laura Harring’s

actual breasts

– was too awful to contemplate. I mean, there was I, idly caressing them, while Harring might well be lying somewhere dreadfully hacked about. In an interview I had read with the actress she said: ‘Life is a beautiful journey. Every episode of my life is like a dream and I am at peace and happy with what life has given me.’ But there was no way she could factor a sadistic double-mastectomy into such a beneficent dream – this was a thieving nightmare. Or had Harring been murdered, her beautiful face beaten to a pulp with a brass statuette of a monkey? If so I was off the hook for libel – but without an alibi for the caesura of the past twelve hours.

Clearly, it was time to force the pace of events: if they were messing with me to this extent I’d better take the fight to them. I leafed through the

Yellow Pages

, found the number, called it and discovered there was a meeting in Hollywood that very morning. Good, I’d have some breakfast, then stroll over.

Slumping in the kitchenette, teapot on the table, and beside it the newly polished brass statuette of a monkey, I poked one long lean thigh languorously out from the folds of the hotel bathrobe. Ignoring the multiple sections of the

LA Times

strewn all around, I felt as iconic as a Terry O’Neill photo which was just as well, because even in a town renowned for sick shit it was going to take some guts to hit the streets with my purloined tits.

I needn’t have worried, by the time I’d shaved and dressed, the breasts – or implants – had begun to subside, becoming first perfectly normal middle-aged bubs and then the budding nubbins of a teenage girl. Locking the door to the bungalow, I slid a hand up under my T-shirt and was relieved to discover coarse hair. The whole tit-thing must have been the after-effect of a particularly polymorphous erotic dream, and although I felt a little cheated it had to be better than murder.

I found the meeting up on Hawthorn in some kind of community centre. There was a Formica table covered with leaflets and a forty-year-old woman with braces

and

a tongue stud serving coffee through a hatch. Savouring the ghostly aroma of last week’s cheap meals, I took one, figuring it was only Nescafé, and thinking also of how it was I walked among them, these seraphic folk, able to suspend disbelief in

films, in TV adverts, in pop songs, in microwaved food – and even in age itself. Maybe – just maybe – this could work for me too.

All the rest of the cast was assembled – exactly the players you’d expect for a self-help production almost anywhere in the maldeveloped world: following men and trailing ladies, character-defect actors, bit failures and spare extras. I slotted right into this stereotypy and no one paid me the least attention as I threw myself down on a canvas bottomed chair, muttering and slurping and giving off that supersonic whine that’s unfailingly associated with mental distress.

I watched and listened as the children of Xenu were called onstage to testify to their treatment at the hands of the cult. This frail girl, all elbows and ears, the ends of her hair as fractured as her psyche, explained how she had been recruited into the Sea

Org

*

at the age of twelve and spent eight years being bullied and abused – four of them as a suppressive person, forced to wear an orange jumpsuit and wield a mop for fourteen hours a day. She wept.

As did a burly man, who said that while he had managed to make the break, his parents – despite everything that had happened to him – continued to believe that they were Thetans who had been exiled to earth 75 million years ago, and that after arriving at an implant station housed in an extinct volcano, they had clung to genetic entity after genetic entity, piggybacking their way through evolution, until they ended up passing out leaflets on Hollywood Boulevard. He himself had had a breakdown after leaving, and when his parents ‘They still love me ...’ – had the temerity to meet with him, they too had been labelled ‘suppressive persons’.

‘You guys know what that’s like,’ he sobbed. ‘Nobody can talk to them, sit with them, hand them a friggin’ cup of coffee – and you know the awfulest thing, I kinda feel that way too. I feel like I’m a suppressive person even out here in the real world – I just can’t connect.’

The testimonies were getting to me. I’d known in general terms the secret arcana that Scientologists became privy to only when they attained the grade of Level 3 Operating Thetans, but still: to hear how this hokum had corrupted minds and distorted

lives was ... salutary. I looked at the slack skin on the backs of my hands. True, it would’ve been a reassurance to be admitted to the religion – neither of the actors playing me was getting any younger, and while I was confident they’d still be having offers for years to come, what kind of parts would they be? I didn’t want to end up in soaps – or sitcoms. Whereas if I were a Thetan, I’d effectively become an actor with a billion-year contract and there’d be no resting at all: as soon as one part (or ‘life’) ended, another would begin—

‘Are you going to join us on the demo?’

‘I’m sorry?’

‘Are you coming with – on the demo?’

I had been romping in my reverie of full and eternal employment, with its personations flowing seamlessly, each into the next, never the dull requirement to

just be myself

, when suddenly there were the braces and the tongue stud and the petty earnestness of it all.

‘Well, uh, where?’

‘We’re going to picket the centre up on Hollywood – you don’t have to if you don’t feel comfortable, I mean, we’d understand.’

‘Sure we would,’ said the burly man, coming up behind her with an ursine undulation of his sloping shoulders. ‘I mean, you could be recognized by someone – and that can cause problems in this town, you could end up as

fair game

.’

I knew what he was talking about: to be branded ‘fair game’ was the Scientological equivalent of being forced to wear a yellow star in Germany after the promulgation of the Nuremberg Laws. Persons designated ‘fair game’ could be ‘deprived of property or injured by any means by any Scientologist’, and this included being ‘tricked, sued, or lied to or destroyed’.

‘I gotta tellya,’ said the burly son of Xenu, leaning down to me conspiratorially, ‘I had no idea you had any involvement with the Church.’

‘Um, well, not

formally

,’ I stressed, ‘but I did go to Saint Hill a few times – y’know, in England.’

‘Sure, sure, I understand – loved you in

Dinotopia

by the way. Lissen.’ He held up a swatch of black cloth and a white mask.

*

‘You could always wear these if you don’t want to be recognized, and we’d be grateful, we could use the numbers.’

I stood up and took the robe and mask from him. ‘Sure,’ I said, ‘I’ll come along – I could use a walk.’

They couldn’t – the children of Xenu piled into a minibus and several cars, leaving me to plod the couple of miles to where the demo was assembling at Hollywood and Vine. They said they’d try to wait – but, as Busner often used to say, ‘Trying is lying.’ I’d been thinking of him on the walk over, and what he’d make of these odd polarities - here was I, joining the anti-Scientology march, while over there, on Sunset, was the office of the Citizens Commission on Human Rights, the anti-psychiatric pressure group szupported by Szasz and the Scientologists.

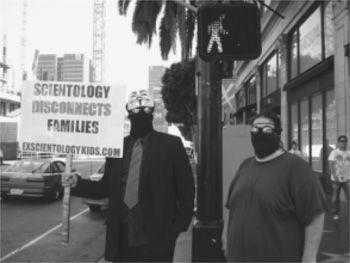

From the corner I could see the Scientology kids wending their way through the crowds along the boulevard, all of them in their V masks, and carrying placards with slogans such

as ‘They Want Your Money and Your Sanity’, ‘Scientology Disconnects Families’ and ‘Tax-Exempt Pyramid Scheme’. This last seemed the most problematic – after all, just about all of late capitalism was founded on a tax-exempt pyramid scheme; or so it seemed to me, on Saturday, 14 June 2008.

I shrugged on my own black robe, donned my V mask, then hustled through the tourists and the cruisers and the movie star impersonators – but the demo kept on marching, while I was only floundering: walking to Hollywood was one thing; running quite another. In a way, it was relief when a van slewed into the kerb beside me, its side door slammed open, and two Mormonesque heavies leapt out, grabbed me and hustled me inside. ‘C’mon,’ said one of them. ‘You’ve done enough walking for a lifetime – why not take a ride.’

The last thing I saw before the door was slammed shut was Margaret Atwood slumped by a storefront, a pathetic styrofoam begging cup on the sidewalk in front of her. I’d had no idea dystopic novels were selling that badly. Then, as the van pulled away, through the tinted rear windows, I spotted Kazuo Ishiguro, the British novelist – another writer who’d had many of his works adapted for screen; but, while to be down and out in Hollywood was one thing, why was he wearing that curious robe, which looked like a couple of camping mats and an election placard strapped round his torso? And what was he wearing on his head? Was it a hat – or a house? And if it was a house – which one? Darlington Hall, as featured in

The Remains of the Day

, or Netherfield Park?

But I had no time to reflect any further on these mysteries, for the van’s driver – who was hidden from me in a sealed compartment – must have seen a break in the traffic and accelerated, and I was thrust backwards on to the point of a

hypo. I felt the drug ooze into me – then my consciousness, tissue-thin to begin with, was balled up, wadded and thrown away.

I get it back standing stark naked in what appears initially to be a featureless room: plain white walls, a high ceiling with recessed lighting diodes. Then I see, lying on the smooth white floor, the silky pool of a Spandex bodysuit. Next, I notice a single prop: a stop light, such as you might see at any LA intersection. It’s working, and as I look it changes from the red

DON’T WALK

to the green stick-figure with its legs parted. There’s no smell at all, except the stray whiffs of my own sweaty armpits – yet I sense altitude and aridity, and wonder if the room might be in a desert, say, the Mojave.