Wallach's Interpretation of Diagnostic Tests: Pathways to Arriving at a Clinical Diagnosis (34 page)

Authors: Mary A. Williamson Mt(ascp) Phd,L. Michael Snyder Md

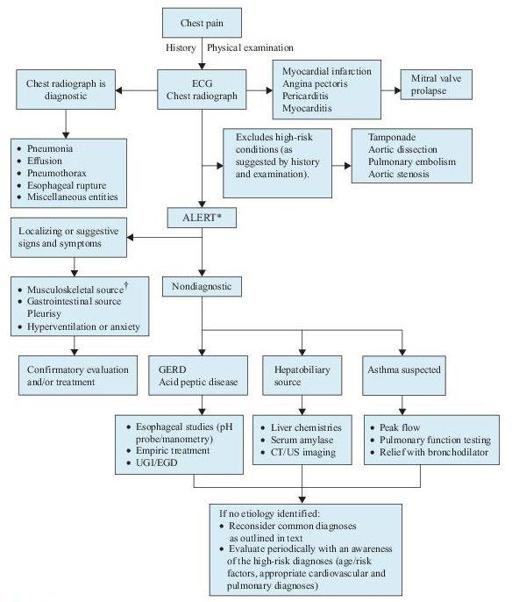

Figure 3–1

Algorithm for the diagnosis of chest pain.

*This algorithm is intended to direct the workup in patients with chest pain of unclear etiology.

†Many of these patients will be discovered to have musculoskeletal syndromes that are diagnosed through a detailed history and physical examination. Musculoskeletal diagnoses to specifically consider include overuse syndromes, costochondritis, pectoral girdle syndrome, and xiphodynia. CT, computed tomography; ECG, electrocardiogram; EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; UGI, upper gastrointestinal series; US, ultrasound.

Laboratory and Additional Testing

While the diagnosis of MI is in part dependent upon laboratory testing, cardiac biomarkers and supplemental imaging may also be utilized for risk stratification and delivery of cost-effective care based on patient risk.

The diagnosis of STEMI is made by clinical history, ECG findings, and, if needed, cardiac imaging. It should not be dependent upon the results of cardiac biomarker assays given the time-dependent nature of reperfusion therapy efficacy in this high-risk population. Stat renal function and CBC to assess for anemia and baseline platelet levels are recommended in patients presenting with STEMI. Cocaine history/tox screen should be considered.

Up to 25% of hospital admissions are due to symptoms consistent with ACS, yet up to 85% of these patients do not have ACS as a final diagnosis. Serial biomarkers with stress testing may help identify low- and intermediate-risk patients who may be safely

discharged home

to continue a cardiovascular evaluation as an outpatient. Based on history, exam, ECG, and laboratory testing, risk assessment may be performed. The presence of ischemic symptoms, hypotension, dynamic ECG changes, heart failure, or advanced age indicates high-risk ACS, and these patients admitted as either NSTEMI (positive biomarkers) or high-risk UA (negative markers).

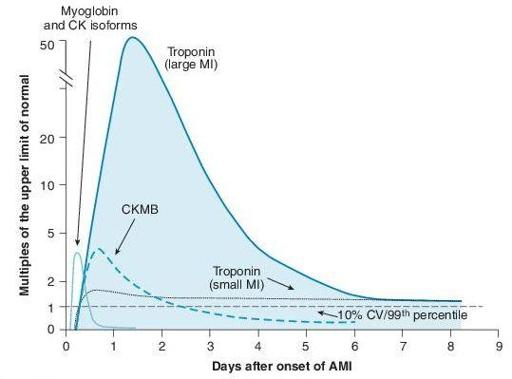

The distinction between NSTEMI and UA is determined by the presence or absence of detectable biomarkers of necrosis. Troponin is widely accepted as the “gold standard” for cardiac myonecrosis and appears in serum 4 hours after onset of ischemia and peaks in 8–12 hours. Patients with negative biomarkers within 6 hours of chest symptoms should have a second set obtained 8–12 hours after symptom onset.

At conclusion of two biomarker evaluations (observed for 8–24 hours postsymptoms), the decision for admission (positive biomarkers) or noninvasive provocative testing (normal biomarkers without high-risk clinical features) may be made (Figure

3-2

).

There are a number of

abbreviated biomarker strategies

(<6 hours) to potentially discharge low-risk patients home earlier than current practice. Due to superior release kinetics, initially CK-MB was used for these protocols. CK-MB has fallen out of favor due to superior troponin sensitivity for MI. Troponin-based protocols incorporate assays performed 2 hours apart combined with either risk model assessment (TIMI score) or potentially imag-ing modalities (CT). While these strategies show promise, due to the use of point-of-care testing, they require institution-specific customization of cutoff thresholds of troponin as point-of-care testing has lower sensitivity than cen-tral laboratory troponin assays (which result more slowly).

The role of very high-sensitivity troponin for rapid assessment (not approved yet in United States) shows promise due to superior sensitivity and earlier detection (hs-TnT 100% sensitivity for MI within 4–6 hours after symptoms or 0–2 hours after ED presentation).

Assessment of platelet reactivity at this point in time cannot be recommended for the diagnosis of ACS.

Figure 3–2

Graph of temporal expression of cardiac biomarkers. Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non

–

ST elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non

–

ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction) developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(7):e1

–

e157.

Without positive biomarkers, low-risk patients (age < 70, no rest pain, pain <2 weeks without prolonged episodes, normal ECG, no prior CAD or diabetes mellitus) may be discharged home and additional evaluation performed as an outpatient. Appointment should be made within 72 hours for evaluation. Intermediaterisk patients without high-risk features require in-hospital triage with provocative noninvasive imaging. The sensitivity and specificity of stress testing can be combined with pretest risk to give a prognosis of coronary heart disease.