Wallach's Interpretation of Diagnostic Tests: Pathways to Arriving at a Clinical Diagnosis (59 page)

Authors: Mary A. Williamson Mt(ascp) Phd,L. Michael Snyder Md

BOOK: Wallach's Interpretation of Diagnostic Tests: Pathways to Arriving at a Clinical Diagnosis

13.17Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Who Should Be Suspected?

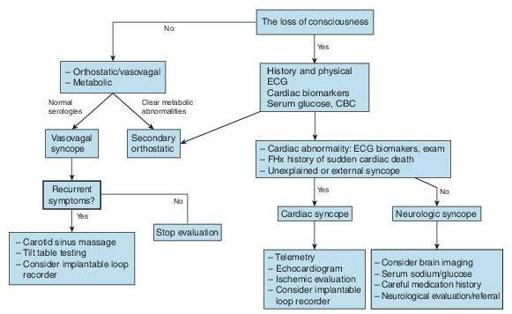

A transient, complete loss of consciousness and postural tone with spontaneous complete recovery without sequelae is likely to be syncope as opposed to a nonsyncopal event with apparent loss of consciousness. Differential of the latter includes seizure, hemorrhage, pulmonary embolism, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and metabolic (hypoglycemia/hypoxia) (Figure

3-3

).

Unlikely seizure disorders, patients rarely experience prolonged disorientation or confusion after syncope.

Syncope occurring with exercise or chest pain should be aggressively evaluated for life-threatening causes such as aortic stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, coronary artery disease, and dysrhythmias.

In both young and elderly patients, orthostatic and neutrally mediated syncope is the most frequent etiology (50–60%) as compared to arrhythmia or structural cardiac disease (20–25%). However, young patients should be screened for family history of sudden cardiac death and the ECG scrutinized for high-risk features (see Diagnostic Testing below). Elderly patients are at a greater risk of adverse outcomes after a syncopal episode, but mortality risk appears to be driven more from the presence of underlying heart disease than age-related risk alone.

A complete list of all medications (prescription and nonprescription) should be obtained in all patients.

Figure 3–3

Evaluation of syncope.

Laboratory and Other Diagnostic Testing

A comprehensive medical history, characterization of the syncopal event with associated triggers, is essential and may yield a diagnosis in up to half of all cases without testing.

Extensive routine laboratory screening is not supported by evidence and rarely yields an etiology. Serum glucose should be assessed, particularly in patients with altered mental status. Electrolyte and renal function should be screened to assess for abnormalities that might cause or aggravate arrhythmias. Complete blood count to assess for anemia is reasonable.

Plasma BNP

may aid in distinguishing cardiac from noncardiac syncope but is not yet endorsed by professional society guidelines. A large prospective study (released after most current guidelines) utilizing a risk-stratification admission algorithm if any of the following were present: BNP ≥300 pg/mL, bradycardia ≤50 bpm, fecal occult blood, anemia with ≤9 g/dL, chest pain, Q waves on ECG, or oxygenation saturation ≤94% had a sensitivity of 87% and specificity of 66% with negative predictive value of 98.5%.

An

electrocardiogram

should be performed in all patients with syncope and is central to risk stratification of patients with syncope. The presence of highrisk features should dictate hospital admission and further evaluation, not the diagnosis of syncope. ECG high-risk features include bifascicular block, QRS ≥0.12 seconds, Mobitz I second-degree AV block, sinus bradycardia (≤50 bpm), or sinus pause ≥3 seconds without chronotropic medications, evidence of preexcitation (Wolf-Parkinson-White syndrome), long or short QT intervals, Brugada syndrome (RBBB with ST elevation V1–V3), and Q waves. Clinical high-risk features that require hospitalization are the presence of cardiac structural disease, family history of sudden cardiac death, severe anemia, palpitations at the time of syncope, exertional syncope, electrolyte disturbances, and severe comorbidities.

Other books

Eric S. Brown by Last Stand in a Dead Land

Francona: The Red Sox Years by Francona, Terry, Shaughnessy, Dan

Mrs. Tim of the Regiment by D. E. Stevenson

Miami Midnight by Davis, Maggie;

Catch A Falling Superstar: A New Adult Erotic Romance by Steen, J. Emily

Crusade by ANDERSON, TAYLOR

As She Left It by Catriona McPherson

Lakewood Memorial by Robert R. Best

Bad Girls in Love by Cynthia Voigt

In the Bag by Kate Klise