Wallach's Interpretation of Diagnostic Tests: Pathways to Arriving at a Clinical Diagnosis (625 page)

Authors: Mary A. Williamson Mt(ascp) Phd,L. Michael Snyder Md

Enzyme multiplied immunoassay technique (EMIT)

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Fluorescence polarization immunoassay (FPIA)

Kinetic interaction of particles (KIMS)

Cloned enzyme donor immunoassay (CEDIA)

Immunoassays are typically qualitative assays, although semiquantitative results are possible with some kits. For qualitative testing, the instrument is calibrated at one concentration, called the cutoff concentration. For example, when utilizing EMIT, all specimens that have absorbance values equivalent to this cutoff calibrator or greater will be reported as positive. Manufacturers provide this calibrator, so the laboratory has no choice in this concentration unless they alter the kit provided (e.g., dilution, to obtain alternate/user-defined cutoffs).

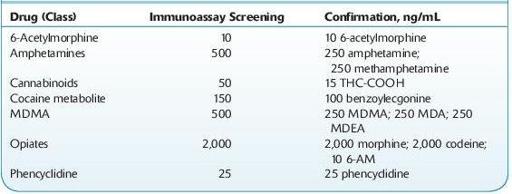

Cutoff concentrations for these kits have historically been decided with reference to the DHHS SAMSHA–mandated cutoffs for federal workplace drug testing, the so-called NIDA5 drugs/classes (PCP, opiates, cannabinoids [marijuana], cocaine metabolite, amphetamines). These cutoff concentrations are not generally appropriate for clinical use, since the cutoff values for several drug–drug classes are fairly high (see Table

14-2

). This decreases the likelihood of false-positive results. The detection of drug abuse rather than legitimate drug use is targeted (see Forensic Toxicology).

TABLE 14–2. U.S. DHHS Cutoff Concentrations for Urine

Practitioners should also be aware of the relative cross-reactivities of the tests ordered. For example, immunoassays for opiates target morphine and typically do not produce positive results with samples containing synthetic and semisynthetic opioids such as oxycodone, fentanyl, propoxyphene, and tramadol.

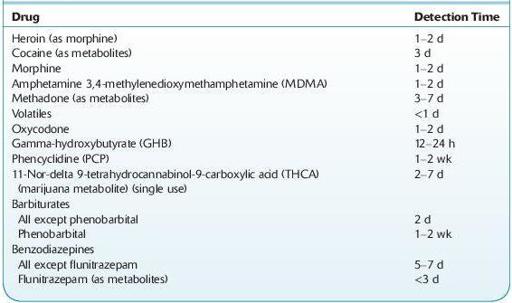

Table

14-3

lists the detection time of several drugs in urine. Note variables that must be considered include dose, frequency and route of administration, formulation, and patient-related factors (e.g., disease, other drugs, genetic polymorphisms).

TABLE 14–3. Approximate Detection Times in Urine of Some Drugs of Abuse

Confirmation Methods and Limitations

Confirmation tests are typically performed following a positive screening result. Confirmatory tests are ordered if it is necessary to identify a specific drug, obtain a quantitative result, or make a determination for legal purposes. For example, a positive opiate immunoassay result will not establish the identity of the opiate. A more specific test is required. These are typically chromatography based and are not performed on a “stat” basis. Chromatography is a separation process based on the differential distribution of sample constituents between a moving mobile and a stationary phase. Chromatography is a separation technique not identification. Mass spectrometry provides identification, since it provides mass and charge information unique to individual drugs. Identification may not be necessary in therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM). Sample pretreatment, extraction, and complex instrumental analysis are required. Common methods used for confirmation tests are

Gas chromatography (GC)

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)

GC/mass spectrometry (GC/MS, GC/MS/MS)

Liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS, LC/MS/MS)

Interpretation of Quantitative Results in Urine

Drug concentrations in urine are not reflective of the dose of drug administered or a specific dosing regimen. Semiquantitative results provided by immunoassays may reflect contributions from more than one drug. For example, a presumptive positive immunoassay screen for opiates may be due to the presence of morphine, heroin, 6-acetylmorphine, and codeine in the specimen. Confirmation testing should provide identification of each drug present and may also provide quantitative results for each specific drug. In these instances, the laboratory may report total or free drug levels, that is, drug present that may be conjugated or unconjugated.

The concentration of drug present in a random urine specimen is the result of the drug delivery system, acute or chronic drug administration, the time of specimen collection, the hydration status of the individual, renal and hepatic function, urine pH, the presence of other drugs resulting in drug interactions, individual pharmacokinetics, and pharmacogenetic polymorphisms. Urine drug/creatinine ratios may be calculated in order to minimize effects on drug concentrations due to changes in the fluid intake of the patient. Monitoring over time may assist in the determination between abstinence and renewed drug use.

Specimen Validity and Drug Testing Background