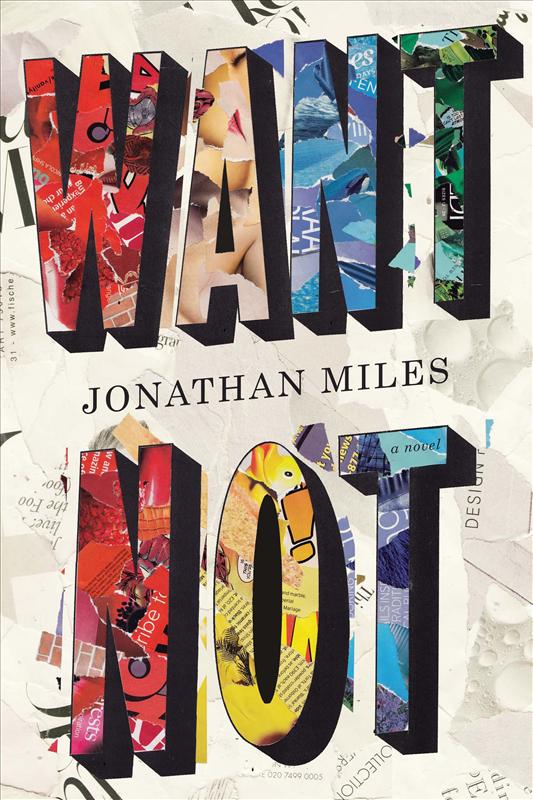

Want Not

Authors: Jonathan Miles

Copyright © 2013 by Jonathan Miles

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Miles, Jonathan.

Want not / Jonathan Miles.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-547-35220-6 (hardback)

I. Title.

PS3613.I5322W36 2013

813'.6—dc23

2013027142

eISBN 978-0-544-11463-0

v1.1113

Excerpt of “The Ridge Farm” from

Sumerian Vistas

by A. R. Ammons. Copyright © 1987 by A. R. Ammons. Used by permission of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

this one’s for

LIZ

and for

DWIGHT & CREE

from their squatter & forever pal

People forget, they cover, they kid themselves, they lie. But their trash always tells the truth.

—William Rathje, archaeologist

the odor of shit is like language,

an unmistakable assimilation of a

use, tone, flavor, accent hard to

fake: enemy shit smells like the enemy:

everything is more nearly incredible

than you thought at first.

—A. R. Ammons, “The Ridge Farm”

To what purpose is this waste?

—Matthew 26:8

THANKSGIVING, 2008

A

LL BUT ONE

of the black trash bags, heaped curbside on East 4th Street, were tufted with fresh snow, and looked, to Talmadge, like alpine peaks in the moonlight, or at least what he, a lifetime flatlander, thought alpine peaks might look like if bathed in moonglow and (upon further reflection) composed of slabs of low-density polyethylene. Admittedly, his mental faculties were still under the vigorous sway of the half gram of Sonoma County Sour Diesel he’d smoked a half hour earlier, but still: Mountains. Definitely. When he brushed the snow off the topmost bag and untied the knot at its summit, he felt like a god disassembling the Earth.

Micah would surely object to this analogy—the problem with dudes, he could hear her saying, is that y’all can’t even open a freaking trash bag without wanting to be some kind of god subjugating the planet—before needling him for making any analogy at all. “You’re, like, the only person in the world who overuses the word ‘like’ the way it’s actually meant to be used,” she’d once told him. Which was true: He was an inveterate analogizer who couldn’t help viewing the world as a matrix of interconnected references in which everything was related to everything else through the associative, magnetizing impulses of his brain. Back in college he’d read that this trait was an indicator of genius or perhaps merely advanced intelligence, and while this had pleased him, he was also aware, darkly, that he’d inherited the trait directly from his Uncle Lenord, which wasn’t a DNA strand he longed to advertise. Uncle Lenord, who repaired riding mowers and weedwhackers and various other small-engine whatnots out of his carport in Wiggins, Mississippi, was a fount of cracker-barrel similes—

hotter’n two foxes fucking in a forest fire; wound up tighter’n an eight-day clock; drunk as a bicycle; spicier’n a goat’s ass in a pepper patch

—but no one had ever accused him of genius-level or even advanced thinking. Frankly no one had ever accused him of any thinking whatsoever, with the possible exception of the girlfriend of one of Talmadge’s Ole Miss fraternity brothers. She’d interviewed Lenord for a Southern Studies 202 term paper about the effects of clear-cut logging on rural communities, so presumably—since the girlfriend scored a B-plus on the paper—Lenord had been forced to think at least once. He debriefed Talmadge on the interview a few weeks later, when Talmadge was home for Christmas break. “Girl had titties out to here,” Lenord confided. “Woulda jumped on that ass like a duck on a Junebug.”

With a gloved hand Talmadge sifted through the bag’s contents: donuts, Portuguese rolls, kaiser rolls, bagels, cookies, cream horns, Swiss rolls, challah, and muffins. The effluvia of the Key Food bakery department, most of it edible but none of it salable, discharged to the curb. He transferred two of the Portuguese rolls and two pistachio muffins into the burlap satchel he wore messenger-style on his shoulder, and then, remembering that Matty was coming to dinner, added another roll and muffin to the bag. Then one more Portuguese roll, and on second thought another, because he remembered that Matty ate like a pulpwood hauler.

The cream horns were fatally smooshed; otherwise he would’ve taken three or four. Weed gave him a monumental sweet tooth. He considered the cookies but they were nestled in a wad of paper towels drenched in something blue—Windex, he guessed. The challah was hard as seasoned firewood, and should have, he noted critically, been thrown out the day before. Ditto the bagels, though he didn’t care about them, since day-old bagels were his easiest prey. Unger’s over on Avenue B had the best ones anyway, and Mr. Unger—testy, fat-jowled, an aproned old relic from the bygone Lower East Side—put out two or three full bags of them nightly. The only problem with those was Mr. Unger himself, who would sometimes charge out of the store to demand payment. Talmadge was always quick to skedaddle but Micah relished the fight. “They’re trash,” she’d say. “They’re

my

trash,” he’d reply. And so on and so forth until Mr. Unger would fling up his arms and shout, “Freeloaders! Freeloaders!” The whole exchange was avoidable since there was a two-hour window between the time that Mr. Unger locked the shop, at seven, and when the Department of Sanitation trucks rolled up at nine, during which time the bagels were free for the loading, but Micah operated on her own narrow terms—angry fat-jowled relics be damned.

After retying the bag and replacing it onto the heap, Talmadge went about frisking the other bags. He was after the pleasant dumpy squish that meant produce, which he found after several gropings. He wrestled the bag off the pile—it was unusually heavy, suggesting melons—and opened it on the sidewalk.

“Five dollars,” he heard someone say. One of the canners at the bottle-redemption machines, about six yards down the sidewalk: a hunched, skittery black guy in a long charcoal overcoat, no taller than five-foot-five though possibly five-foot-ten if he would or could stand up straight, and while he looked about eighty—owing partly to his posture, but also his rheumy eyes which were capped with the kind of wildly unkempt and woolly gray eyebrows one saw in portraits of nineteenth-century lunatics—he was probably closer to sixty. With an empty plastic bag hanging from his hand, he was staring at the machine marked

CANS

as if squaring off against it in a brawl.

“Five fucking dollars,” he said to it. He looked to his left, where a short, disfigured Chinese woman was waiting with a can-filled handcart and where another canner Talmadge called Scatman—grizzly-sized from the multiple overcoats he was wearing, and sporting his trademark vintage earphones—was feeding a huge cache of Evian bottles into the maw of the

PLASTICS

machine; then to his right, where Talmadge was watching him with an opened bag of mucky produce at his feet; and then finally upward to where a sign, perched above the bank of machines, read

AUTOMATIC REDEMPTION CENTER

. Talmadge had once suggested, jokingly, that he and Micah ought to transplant the sign to the Most Holy Redeemer Church around the corner on 3rd Street. She didn’t think it was funny but then funny wasn’t her thing.

Scatman wasn’t scatting. Usually he serenaded his deposits, and accompanied his collecting, with mumbled scat-singing, or something resembling it:

skippity dip da doo, bop de-diddlee, bam bam bam.

Hence the nickname. Talmadge wasn’t sure whether Scatman’s vinyl-covered earphones—padded and brown and big as coconut halves—were related to the scatting, or if indeed they were even connected to anything, but he’d never seen Scatman without them, in warm weather or cold, so he supposed they served some function. As for the Chinese woman: Talmadge knew her, or was anyway familiar with her. She was a part-time canner who walked a fixed route in the early evenings, plucking cans out of the corner trash barrels with a plastic, purple-and-lime green pincing tool of the kind sold in toy stores. Their paths crossed often enough that she and Talmadge would sometimes acknowledge each other with a flick of eye contact or more rarely a nod. He called her Teeter, because the grievous shortness of one of her legs caused her to teeter down the street. But Hunch, and his five dollars—he was someone new.

“That’s what I get?” he was saying to Teeter. “Five dollars?” She crinkled her face but said nothing. He looked back at the machine. “Well, mothafucka,” he said, and chewed his lip for a moment. “Yo, man,” he said to Scatman. “Five dollars. That right?”

“If that’s what it say,” said Scatman, without looking over, and in a voice Talmadge found mildly startling: Scatman spoke with the smooth basso timbre of an old-timey broadcaster. Smoother than that, even: a

parody

of an old-timey broadcaster. Talmadge had never heard Scatman utter words before, only the

bip

s and

bam

s and

ba-ding

s of his scatting, spluttered and muttered with all the grace and suavity of someone with an index finger lodged in an electrical socket. He’d reasonably expected to hear something more jagged.

“Motha-motha

fucka,

” said Hunch, and then hit the machine with the side of his fist, rattling the fiberglass panel and blinking the lightbulb inside. This, now—this was more than mildly startling. Teeter flinched, then looked down toward the cans in her cart, pretending to notice something new about them. Scatman kept plugging away, staring straight ahead, his scat-free silence further starkening the moment. Talmadge was too busy watching their reactions, the gears of his brain gummed up by the sinsemilla, to monitor his own—something he realized too late. Before he could dip his hand into the produce, and with it the direction of his gaze, Hunch swung his own gaze toward Talmadge and shouted, “The fuck you looking at?”

Houston Crabtree was his name, and if he knew that Talmadge had christened him Hunch he might have tried corking Talmadge’s mouth with a five-cent redeemable Coke can. Might have, that is, rather than would have, because a simple assault charge was an express ticket back upstate to the Mid-Orange lockup. And, most likely, to twelve weeks of Aggression Replacement Training: for Crabtree, the motherfucking cherry on top. Not that he’d ever let consequences stop him before. The first kid who’d called him a hunchback—this was back in Georgia, midcentury—found a baseball bat ringing his larynx. Kid was just seven years old but talked like Bobby Blue Bland after that. As a baby Crabtree had rickets, which’d crooked his spine, bent it like a fish hook, and the older he got, the worse his spine hurt, and the higher he needed to be just to roll out of bed. Some days, it was like walking around with an arrow sticking halfway out his back. Today, for instance. Today it

hurt.

Reaching in to those corner trash cans, stooping to root through those recycling bins, hauling that plastic bag over his shoulder like some dollar-store Santa Claus: today was like having a whole

quiver

of arrows jutting from his back. Today was a motherfucking Injun

massacre.

And all for five dollars. Five even: the precise amount, to the penny, of his urinalysis testing fee. Five dollars, and now this fatassed Don Cornelius saying “If that’s what it say,” like that’s what it

didn’t

say, and weeble-wobble Ching Chong behind him with a whole

truckload

of cans, maybe enough cans to clear his back parole fees

and

get a steak, a cheeseburger, whatever, anything besides that no-turkey turkey soup at the Renewed Horizons shelter. Five dollars, and now this glassy-eyed white kid staring at him as if there really

were

bloody arrows stubbling his back. “Yo,” he said, angling a few steps closer to Talmadge. “I said, the fuck you looking at?”