War Without Garlands: Operation Barbarossa 1941-1942 (27 page)

Read War Without Garlands: Operation Barbarossa 1941-1942 Online

Authors: Robert Kershaw

On the outskirts of Lvov, a similar picture was evident in the Russian 32nd Tank Division sector. Stephan Matysh, the artillery commander, had seen that superior T-34 and KV tanks had exacted many casualties. Russian tank crews were well aware of their superior armour, ‘sometimes even ramming [German] tanks’, but cumulative pressure was beginning to tell.

‘The incessant gruelling marches and the continuous fighting over several days had taxed the tank crews to the utmost. Since the beginning of the war the officers and men had not had a single hour’s rest and they seldom had a hot meal. Our physical strength was leaving us. We desperately needed rest.’

(9)

Colonel Sandalov, the Soviet Fourth Army Chief of Staff, had established the Army HQ in a forest grove east of Siniavka. With no radio communications whatsoever, he was reliant on messenger traffic alone. He reported the outcome of consistent and crushing blows inflicted on his forces by Guderian’s Panzergruppe 2 and Fourth German Army following its central route. Sandalov’s 6th and 42nd Rifle Divisions had already withdrawn eastwards with ‘remnants [which] do not have combat capability’. The 55th Rifle Division, having unloaded from motor transport, was quickly pushed from its rapidly established defence line, ‘unable to withstand an attack of enemy infantry with motor-mechanised units and strong aviation preparation’. No word had been heard of the 49th Rifle Division since the invasion. The XIVth Mechanised Corps, ‘dynamically defending and going over to counter-attacks several times, suffered large losses in material and personnel’, and by 25 June ‘no longer had combat capability’. Paralysis afflicted the Soviet defence:

‘Because of constant fierce bombing, the infantry is demoralised and not showing stubbornness in the defence. Army commanders of all formations must stop sub-units and sometimes even units withdrawing in disorder and turn them back to the front, although these measures, despite even the use of weapons, are not having the required effect.’

(10)

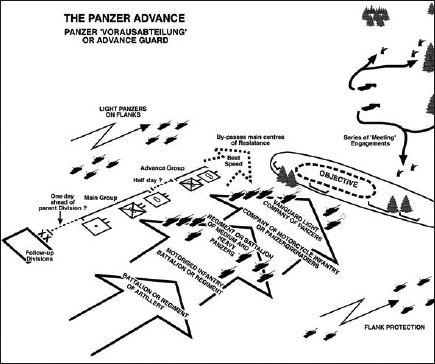

A diagramatic representation of the Panzer advance. The vanguard – a light mixed force of Panzers and motorised infantry – would seek the line of least resistance. Once battle was joined, this lead element would ‘fix’ the objective while following heavier elements would manoeuvre, bypass, destroy or surround enemy resistance, relying upon later echelons to subjugate stay-behind elements. Fighting was generally in the form of meeting engagements shown top right) whereby junior commanders would exercise iniative to retain the tactical and operational momentum of the advance.

Konstantin Simonov, on the Minsk highway under German air attack, remembered a Soviet soldier shell-shocked by the bombing fleeing down the road shrieking: ‘Run! The Germans have surrounded us! We’re finished!’ A Soviet officer called out, ‘Shoot him, shoot that panic-monger!’ Shots began to ring out as the man whose ‘eyes seemed to be crawling out of their sockets’ fled.

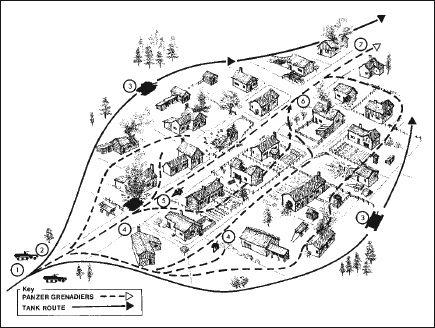

Village clearance would occur once Panzer forces had isolated the settlements. Panzer-grenadier infantry would be committed with tank fire support shooting them in from the flanks, at an acute angle to advancing troops. Artillery and Luftwaffe air support might be employed to precede the attack, prevent the insertion of Russian reinforcements and harrass the eventual retreat. Achieving tactical momentum was of paramount importance.

Legend

- Panzers and infantry split. Infantry lead attack on village.

- Infantry dismount.

- Panzers bypass and give fire support.

- Panzer and anti-tank gun in direct fire support.

- Infantry fight through village with man-handled anti-tank gun support.

- Surviving Russians surrender or flee.

- Grenadiers remount and with Panzers continue the advance.

‘Evidently we did not hit him, as he ran off further. A captain jumped out in his path and, trying to hold him, grasped his rifle. It went off and, frightened still more by this shot, the fugitive, like a hunted animal, turned round and with his bayonet rushed at the captain. The latter took out his pistol and shot him. Three or four men silently dragged the body off the road.’

(11)

A collapse appeared imminent.

A typical vanguard for a Panzer division in open terrain would consist of a mixed battalion-strength force of light armour and motorcycle-borne infantry. These were the ‘eyes and ears’ of following units (see diagram) which might include a battalion or regiment of Panzers, supported by motorised infantry at similar strength, riding on lorries or Panzergrenadiers in armoured half-track open-compartment APCs (armoured personnel carriers). Bringing up the rear would be a battalion – or even up to a regiment – of motorised towed-artillery, to provide close fire support. Light Panzer armoured cars or tracked vehicles (PzKpfwIs or IIs) would drive either side of parallel moving columns, forming a protective screen to the flank. Such a lead element in total was termed a Voraus-abteilung or vanguard combat team. It might vary in size from a battalion to a regiment plus.

Depending on terrain going’, units would move in dust-shrouded columns, several kilometres long. Leading reconnaissance elements were often tactically dispersed on a broad front, but many follow-on units simply drove at best speed, spaced at regular intervals. Three columns might advance in parallel if sufficient routes were available. Often they were not. Map-reading in choking dust-covered and packed columns was difficult. Crewmen would sleep fitfully wherever they could, as they bumped and lurched along in vehicles. These Panzer Keile (armoured spearhead-wedges) might operate from roads or spread out in tactical formation if terrain and ground conditions allowed. In woodand or ‘close country’ (bushes and scrub), the infantry would lead, clearing defiles, choke points or woodland, with tanks overlooking, prepared to give fire support. Open steppe-like terrain would see Panzers leading. War correspondent Arthur Grimm, following such a Vorausabteilung at the end of June, gave an atmospheric description of his observed axis of advance:

‘The landscape stretches flat ahead with wave-like undulations. There are few trees and little woodland. Trees are covered in dust, their leaves a dull colour in the brilliant sunlight. The countryside is a brown-grey green with occasional yellow expanses of corn. Over everything hangs a brown-grey pall of smoke, rising from knocked-out tanks and burning villages.’

Panzer crewmen have a different battle perspective compared to infantry on their feet. Scenery, as a consequence of greater mobility, changes quickly and more often. Maps are read from a different vista in terms of time, distance and scale. Panzers quickly crossed maps. Infantrymen saw each horizon approaching through a veil of sweat and exhaustion. Following armoured formations made infantry feel more secure – often a false assumption, but it did mean that friendly forces were known to be ahead. A new horizon for the tank soldier meant an unknown and, very likely, a threatening situation. His was an impartial war, fought at distance. Technology separated him from direct enemy contact: he normally fought with stand-off weapon systems at great range. When direct fighting did occur, it was all the more emotive for its suddenness and intensity. Grimm stated:

‘Scattered trees and wide cornfields are not pleasing to the eye, as they mean danger to us. Gun reports crack out from beneath every tree and from within every field of corn.’

(1)

It was the accompanying supporting troops who closed with the enemy and saw him in the flesh. Anti-tank gunner Helmut Pole recalled the deep impression early Soviet resistance had upon him and his comrades.

‘During the advance we came up against the light T-26 tank, which we could easily knock out, even with the 37mm. There was a Russian hanging in the turret who continued to shoot at us from above with a pistol, as we approached. He was dangling inside without legs, having lost them when the tank was hit. Despite this, he still shot at us with his pistol.’

(2)

Little can be seen from the claustrophobic confines of a tank closed down for battle. Fighting was conducted peering through letter-box size – or smaller – vision blocks in a hot, restricted and crowded fighting compartment with barely room to move. Each report from the main armament or the chattering metallic burst of turret machine gun fire would deafen the crew and release noxious fumes into the cramped space. Tension inside would be high, magnified throughout by a prickling sense of vulnerability to incoming anti-tank round strikes, anticipated at any time. These projectiles were easily seen flying about the battlefield as white-hot slugs, with the potential to screech through a fighting compartment and obliterate all in its path. The kinetic energy produced by the strike set off ammunition fires, searing the fighting compartment in a momentary flash, followed by an explosive pressure wave blasting outward through turret hatches, openings or lifting the entire turret into the air. An external strike by a high-explosive (HE) warhead would break off a metal ‘scab’ inside; propelled by the shock of the explosion, this would ricochet around the cramped interior of the tank. The results were horrific. Flesh seared by the initial combustible flash was then lacerated by jagged white-hot shrapnel, which in turn set off multiple secondary explosions.

Tank crewmen were muffled to some extent from battle noises outside the turret, because the screams were dulled by the noise and vibration of the engine. Human senses were ceaselessly buffeted by violent knocks and lurches as the tank rapidly manoeuvred into firing positions. Dust would well up inside upon halting, and petrol and oil smells would assail nostrils during momentary pauses. A grimy taste soured mouths already dried of spittle by fear. Tank gunner Karl Fuchs from Panzer Regiment 25 admitted to his wife:

‘The impressions that the battles have left on me will be with me forever. Believe me, dearest, when you see me again, you will face quite a different person, a person who has learned the harsh command: “I will survive!” You can’t afford to be soft in war, otherwise you will die.’

(3)

Fatigue and fear went hand in hand. Unteroffizier Hans Becker of the 12th Panzer Division spoke of Panzer battles at Tarnopol and Dubno:

‘Where we had no rest for three days or nights: for rearming and refuelling we were withdrawn not by units but tank by tank and then hurled immediately into the fray again. I put one enemy tank out of action at Tarnopol and four at Dubno, where the countryside became an inferno of death and confusion.’

(4)

Motorised infantry units alongside were subjected to the same persistent and physically demanding pressures. Hauptsturmführer Klinter, a company commander with the vehicle-borne SS ‘Toten-kopf’ Infantry Regiment, which was part of Army Group North, remembered in the first few weeks of the Russian campaign that ‘all the basic tactical principles we had learned appeared to be forgotten’. There was hardly any reconnaissance, no precise orders groups, or few accurate reports, because the situation was fast-moving and constantly changing. ‘It was a completely successful fox hunt,’ he said, ‘into a totally unknown environment, with only one aim in sight – St Petersburg!’

Maps were either incorrect or inadequate. As a result, columns separated on the line of march would often drive off along the wrong route when they reached a junction. Road signing was in its infancy in a rapidly developing tactical situation. ‘So every driver, in complete darkness, observing totally blacked-out conditions and at varying speeds, had to try to remain close together driving in tight columns.’

(5)

Driving continuously day and night, in such conditions was nerve-racking and exhausting.