War Without Garlands: Operation Barbarossa 1941-1942 (25 page)

Read War Without Garlands: Operation Barbarossa 1941-1942 Online

Authors: Robert Kershaw

The sun bore down mercilessly throughout the sixth day of the siege. Most of the citadel and North Island had been cleared but the

Ostfort

tower still held out. Russian dead, swelling grotesquely in the blistering heat, were tipped into ditches and covered with lime and earth, to alleviate the stench. In the River Bug shallows, German dinghies were reaping a similar dreadful harvest of swollen German dead bodies snagging among the reeds. There seemed no limit to the interminable suffering experienced by the Russian defenders. ‘Everything burned,’ explained Katschowa Lesnewna, a surgical sister, ‘the houses, even the trees, everything burned.’ The condition of the wounded became increasingly critical:

‘We used our underclothes as bandages. We had no water. The wounded shook… Although there was water next to us, it was under fire. Sometimes we got a bucket into it, but there were only a few drops to distribute. We risked our lives for it, but it was sufficient only to wet the lips of the wounded. They were desperate for it, and appealed – “Sister, sister, water”, but we couldn’t give them any.’

(14)

During the morning of 28 June the surviving two tanks from Panzer Platoon 28 were reinforced by a number of repaired self-propelled guns. They continued to shoot up the windows and apertures of the

Ostfort,

but with no apparent result. An 88mm Flak gun was pulled forward and began to engage in the direct-fire mode. Again, there was no sign of surrender. To break the impasse Generalmajor Schlieper, the commander of 45th Division, despatched a request to the Luftwaffe airfield nearby at Malasze-wieze to administer an aerial

coup de grâce

to this final stubborn strongpoint. Once the air attack was agreed, the forward German attacking elements had to be withdrawn to the outer fortress wall as a safely measure. Low cloud that afternoon caused the postponement of the solitary Luftwaffe mission. Reluctantly the investing ring was pulled in tightly again to prevent break-outs. Searchlights illuminated the walls all night. Any careless approach venturing too near the fort was immediately engaged by vicious bursts of automatic fire. Tracer continually spat out from this totally isolated outpost. Would it ever capitulate?

On 29 June the news blackout ended in the Reich.

Sonder-meldung

or special news bulletin 1, preceded by the Liszt ‘Russian fanfare’ announced that ‘the Soviet Air Force had been totally destroyed’. Bulletin number 2 announced, ‘the strong enemy border defences were in part broken, even on the first day’. Victory after victory received commentary in a series of statements that exuded satisfaction. ‘On 23 June the enemy directed rabid counterattacks against the vanguards of our attacking columns’ yet ‘the German soldier remained victorious’. Place names at last emerged. It was stated the fortress of Grodno had been taken after hard fighting. ‘The last strongpoint in the Citadel at Brest-Litovsk was stormed by our troops on 24 June.’ Vilnius and Kowno were taken. In all, 12 special bulletins were sonorously announced one after the other on 29 June.

(15)

‘Two Red Armies trapped east of Bialystok,’ Goebbels gloated. ‘No chance of a break-out. Minsk is in our hands.’ Although a glut of information was released, the Reich audience was not totally feckless. Goebbels perceptively admitted to his diary:

‘It is all too much at once. By the end, one can sense a slight numbness in the way they receive the news. The effect is not what we had hoped for. The listeners can see through our manipulation of the news too clearly. It is all laid on too thickly, in their opinion… Nevertheless the effect is still tremendous … We are back at the pinnacle of triumph.’

(16)

His comment was echoed in an SS Secret Service report the following day which concurred that ‘summarising the 12 Special Announcements within two or three reports would have been better received’. Despite the feverish anticipation of good news, the extent of the successes came as a general surprise. Media releases were ‘almost unbelievable’, particularly the numbers of Soviet tanks and aircraft destroyed. Rumours continued, because it became obvious from the

Sondermeldungen

dates that more would follow. ‘With total lack of judgement,’ the SS report commented, ‘in some areas it was being wagered that the German Wehrmacht was likely to appear in Moscow on Sunday’.

(17)

These were ‘heady days’. More was to follow as the Blitzkrieg gathered momentum towards Smolensk.

Blitzkrieg

‘We hardly had any sleep because we drove through both day and night.’

Panzer platoon commander

The ‘smooth’ period… The Panzers

Generalfeldmarschall von Bock, the commander of Army Group Centre, felt exasperated as he turned his two Panzergruppen – 2 and 3 – inwards to complete the first major encirclement of the Russian campaign after being denied the greater prize at Smolensk. It was, nevertheless, a stunning achievement. ‘I was still so annoyed by the order to close the pocket prematurely’ wrote von Bock in his diary, that when visited by Generalfeldmarschall von Brauchitsch, the Commander-in-Chief, his response to congratulations was a gruff ‘I doubt there’s anything left inside now!’

(1)

The 250–300km Panzer advance beginning to curl around the trapped Soviet forces was about to net some 27 Russian divisions.

Major Johann Graf von Kielmansegg, a Panzer commander with the 6th Division, later explained that the nature of the fighting on the ground belied the impressive achievements trumpeted to the world’s press. It was no walk-over. The Soviet border defences ‘were certainly surprised’, he said, ‘but not overrun’.

(2)

Leutnant Helmut Ritgen, serving in the same division, concurred.

‘Since nobody surrendered, almost no prisoners were taken. Our tanks, however, were soon out of ammunition, a case which had never happened before in either Poland or France.’

(3)

The ‘smooth’ period of the Panzer advance von Kielmansegg described ‘lay between two parts’:

‘The first was the battles fought directly on the frontier – these were very very hard. Next came a blocking action on the so-called “Stalin Line”, which was where Russian reinforcements were fed in. But to speak of “overrunning”, even though Goebbels may have been asserting this, was an overstatement from the start.’

(4)

The ‘smooth’ period was testimony to German tactical superiority, conferred by the collective experience of the previous successful campaigns. ‘In three days I have slept for two hours and one attack has followed the other,’ wrote war correspondent Arthur Grimm, advancing with elements of Panzergruppe 1 under von Kleist with Army Group South.

‘The enemy cannot hold us and constantly attempts to pin us down in a major engagement. But we are always forewarned in time and bypass him in ghostly night drives.’

(5)

An unpleasant surprise for the supremely confident Panzer troops was the quality of some of the Soviet equipments they soon faced.

On the second day of the campaign, in the 6th Panzer Division sector, 12 German supply trucks were knocked out, one after the other, by a solitary unidentified Soviet heavy tank. The vehicle sat astride the road south of the River Dubysa near Rossieny. Further beyond, two German combat teams had already established bridgeheads on the other side of the river. They were about to be engaged in the first major tank battle of the eastern campaign. Their urgent resupply requirements had already been destroyed. Rutted muddy approaches and a nearby forest infested with bands of stay-behind Russian infantry negated any option to bypass. The Russian tank had to be eliminated. A battery of medium 50mm German antitank guns was sent forward to force the route.

The guns were skilfully manhandled by their crews through close terrain up to within 600m of their intended target. Three red-hot tracer-based shells spat out at 823m/sec, smacking into the tank with rapid and resounding ‘plunks’ one after the other. At first there was cheering but the crews became concerned as these and another five rounds spun majestically into the air as they ricocheted off the armour of the unknown tank type. Its turret came to life and remorselessly traversed in their direction. Within minutes the entire battery was silenced by a lethal succession of 76mm HE shells that tore into them. Casualties were heavy.

Meanwhile a well-camouflaged 88mm Flak gun carefully crept forward, slowly towed by its half-track tractor, winding its way among cover provided by the 12 burnt-out German trucks strewn about the road. It got to within 900m of the Soviet tank before a further 76mm round spat out, spinning the gun into a roadside ditch. The crew, caught in the act of manhandling the trails into position, were mown down by a swathe of coaxial machine gun fire. Every shell fired by the Russian tank appeared to be a strike. Nothing moved until nightfall when, under the cover of darkness, it was safe enough to recover the dead and wounded and salvage some of the knocked-out equipments.

An inconclusive raid was mounted that night by assault engineers who managed to attach two demolition charges onto this still, as yet, unidentified tank type. Both charges exploded, but retaliatory turret fire confirmed the tank was still in action. Three attacks had failed. Dive-bomber support was requested but not available. A fourth attack plan was developed involving a further 88mm Flak gun, supported this time by light Panzers which were to feint and provide covering fire in a co-ordinated daylight operation.

Panzers, utilising tree cover, skirmished forward and began to engage the solitary tank from three directions. This confused the Russian tank which, in attempting to duel with these fast-moving and fleeting targets, was struck in the rear by the newly positioned 88mm Flak gun. Three rounds bore into the hull at over 1,000m/sec. The turret traversed rearward and stopped. There was no sign of an explosion or fire so a further four rounds smashed remorselessly into the apparently helpless target. Spent ricochets spun white-hot to the ground followed by the metallic signatures of direct impacts. Unexpectedly the Soviet gun barrel abruptly jerked skyward. With the engagement over at last, the nearest German troops moved forward to inspect their victim.

Excited and chattering they clambered aboard the armoured colossus. They had never seen such a tank before. Suddenly the turret began to rotate again and the soldiers frantically scattered. Two engineers had the presence of mind to drop two stick grenades into the interior of the tank, through one of the holes pierced by the shot at the base of the turret. Muffled explosions followed and the turret hatch clattered open with an exhalation of smoke. Peering inside the assault engineers could just make out the mutilated remains of the crew. This single tank had blocked forward-replenishment to the 6th Panzer Division vanguard for 48 hours. Only two 88mm shells actually penetrated the armour; five others had gouged deep dents. Eight carbonised blue marks were the only indication of 50mm gun impacts. There was no trace at all of the supporting Panzer strikes, many of which had clearly been seen to hit.

The nature of the enemy armoured threat had irretrievably altered. General Halder wrote in his diary that night:

‘New heavy enemy tank!… A new feature in the sectors of Army Group South and Army Group North is the new heavy Russian tanks, reportedly to be armed with 8cm guns and, according to another but untrustworthy observation from Army Group North, even 15cm guns.’

(6)

This was the KV-1 (Klim Voroshilov) which mounted a 76.2mm gun. Its sister variant, the KV-2, although more unwieldy, did have a 15cm gun. In 1940, 243 of the former and 115 T-34 tanks had been produced, rising to 582 and 1,200 respectively by 1941.

(7)

The Russian-German tank balance was grossly distorted to the Soviet advantage in both quality and quantity. There were 18,782 various Russian tank types versus 3,648 German in 1941.

(8)

German Panzers in weight, main armament, operating distances and speed were generally inferior to Russian tanks.

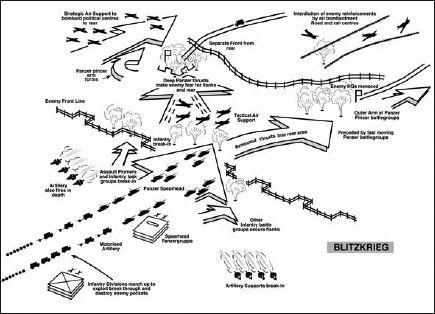

The prelude to a Blitzkrieg advance was the shattering of the enemy front at the main German point of effort, preceded by a joint artillery and air bombardment with an infantry break-in battle. The Panzers were then passed through to strike deep into the enemy rear, intimately supported by tactical air sorties and motorised artillery to overrun headquarters and break up logistic support areas. These armoured units moving at best speed would form pincer ‘arms’ which would then encircle and cut off retreating Russian forces, penning them into pockets to be subdued later by following marching foot infantry.