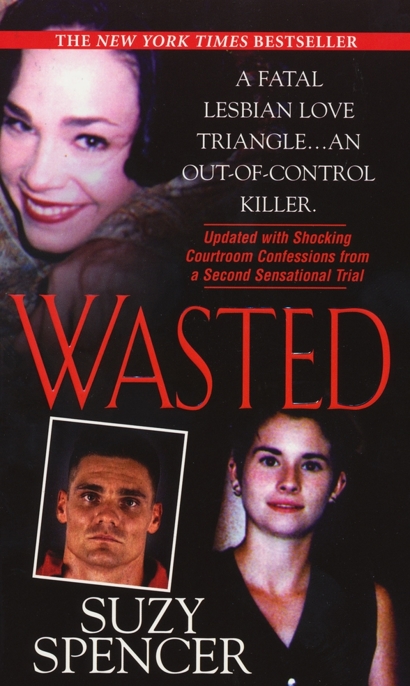

Wasted

“PUT THE SON OF A BITCH ON THE PHONE!”

Justin Thomas grabbed the phone away from Kim LeBlanc. “Look would you quit calling over here and arguing,” he yelled into it at Regina Hartwell. “Quit your goddamned yelling. Quit your goddamned screaming, you know what I’m saying. It’s pointless for y’all to fight and argue if y’all can’t talk right.”

“I can get you screwed,” said Hartwell.

Thomas laughed. LeBlanc was terrified as she listened in on the extension. But Justin had dealt with real threats before, drug-family threats. Regina was just talking out of the side of her mouth. And he knew that.

“Just leave it alone, bitch,” he shouted.

“If you hurt Kim,” Hartwell screamed, “I’ll have you—”

“Don’t call if you’re going to argue and threaten me.” Justin hung up.

Kim stayed on the line.

“I can have the son of a bitch thrown in prison,” Regina yelled to her.

The screaming voices raced through Kim’s head and she felt caught. She hung up only to hear Justin yelling at her, too.

“I ain’t letting nobody send me to prison. Especially not some coke-snorting lesbian bitch. Ain’t nobody sending me to prison! And I’m going to make damn sure of that, with or without you.”

WASTED

SUZY SPENCER

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

“PUT THE SON OF A BITCH ON THE PHONE!”

Title Page

Dedication

PROLOGUE

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

CHAPTER 24

CHAPTER 25

CHAPTER 26

CHAPTER 27

AUTHOR’S NOTE

POSTSCRIPT: THE SECOND TRIAL

GREAT BOOKS, GREAT SAVINGS!

Copyright Page

Title Page

Dedication

PROLOGUE

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

CHAPTER 24

CHAPTER 25

CHAPTER 26

CHAPTER 27

AUTHOR’S NOTE

POSTSCRIPT: THE SECOND TRIAL

GREAT BOOKS, GREAT SAVINGS!

Copyright Page

To my many friends and family who have the serenity to accept the things they cannot change and the courage to change the things they can.

PROLOGUE

Thursday, June 29, 1995, intermittent thunderstorms steadied the temperature near 80 degrees. Ninety percent humidity, though, provoked an easy, morning sweat. This was Texas.

In fact, it was Austin, Texas, home of high-tech millionaires and teenaged slackers, show-biz liberals, poor Hispanics, proud rednecks, environmentalists, and Fundamentalists.

It was a state capital full of bumper stickers reading, “On Earth as it is in Austin” and “Impeach Billary.” Both stickers were plastered to the rusted fenders of old hippie vans, to the shiny rears of new Chevy Suburbans, to the scratched bumpers of dual-wheeled pickup trucks, even a Mercedes or two.

In the heat of the day, they all whizzed down Lamar Boulevard, a hectic street that wound from far north Austin to deep south Austin. Lamar cut past the Yellow Rose stripper bar, the State School for the Blind, through downtown, and across Town Lake—a vein of the Colorado River.

There, oak trees that looked like wise Indian chiefs, grew beside fast-food restaurants frequented by cops and prosecutors. Tanned, homeless men and women and vendors of tie-dyed T-shirts stood on corners near print shops, car washes, and nondescript apartment buildings.

One of those nondescript buildings on South Lamar was the Château. A three-story complex rising high on a hill, the Château was hidden behind a long, tall, plain, concrete wall. The wall looked ripe for gang graffiti, but rarely was graffiti there.

Occasionally a dead body was found down by the lake, over by the train tracks, but it was usually the body of a transient. Crime was less rampant in this neighborhood than one might have thought.

During the daytime, the Château was a quiet complex. It had one obscure driveway off Lamar, and two narrow back drives that exited onto the tiny residential street behind. Around noon, there were three, maybe four or five cars in the parking lot. Rarely, at that time of day, was anyone seen.

So no one noticed as a 6’4”, handsome drug dealer and addict climbed the backstairs of the Château, a building known to police as a gay and lesbian residence. He strolled into an apartment on the second floor, easily. The doorway was shielded from the walkway by hallways, and the door was unlocked. It usually was. He knew that. He’d been there many times. Just a few weeks before, he’d stayed there while its twenty-five-year-old tenant, Regina Hartwell, vacationed in Cancun, Mexico.

He glanced at Regina’s greyhound-whippet mutt Spirit and her mangy cat Ebenezer, the one with the bare-haired tail. They greeted him, and they smelled the enemy. He pushed them aside and walked on into the living room. The scent of Regina filled the place. Her scent was a bit musky: a lot of perfume—Bijan, her favorite—the dog, the cat. He glanced around.

Empty Marlboro cigarette packs and empty beer bottles covered the black-and-white-checkered coffee table. So did photos of Kim LeBlanc. Kim alone. Kim and Regina hugging. His hazel-green eyes lingered on the photos. He felt his adrenaline start to pump. He looked down at Regina.

She lay on the living room couch, groggy. Only three or four hours had passed since her last drink. Even fewer had passed since her last Valium. She wore a purple T-shirt, just like he did. She had on Garfield boxer shorts with red hearts and “Eat Your Heart Out” printed on the fabric.

Her white, crepe paper-skinned legs from too-much, too-fast weight loss shone. She was only 5’1” tall and 110 pounds, having dropped thirty pounds in a mere three weeks. The tattoo on her ankle seemed smudged.

She had on dark blue, cotton panties and was having her period. She raised up and said matter of factly, “What up, Jay?”

“Hi, Reg,” he said.

But Regina’s hazel eyes betrayed her.

He sat down by the couch. His adrenaline pumped harder.

She knew she was about to die.

He lifted a single-edged knife.

Regina went numb with fear. She fought.

He hadn’t expected that.

Hard, fast, she fought him. Fear made her strong, and fear made her feel no pain. It always had. She knocked the knife out of his fist, grabbed it, and sliced the webbing of his right hand.

The adrenaline coursed through his body as the blood squirted out of his hand. He was infuriated. He wasn’t going to settle for this. Not this martial arts expert. Not this infantryman. He wrestled the weapon back from her.

He hammered the knife into the front of Regina’s neck, one swift, precise blow, five, six inches deep. He severed her vein, then an artery, then the upper lobe of her right lung. Finally, the knife stopped deep between the fourth and fifth ribs of Regina’s back.

He waited.

Two to three minutes later, she was unconscious.

He rested.

Five minutes more and Regina Hartwell was dead, drowned in her own blood.

CHAPTER 1

Terry Duval, fire chief of the Bluebonnet Volunteer Fire Department in rural Bastrop County, Texas, was putting his crew through their usual Thursday night drills. That night, it was truck training. There were fifteen to twenty volunteers, many of them teenaged, junior firefighters, working in a light, summer rain.

At 9:38 p.m., Duval received a page—vehicle fire on Farm to Market Road 1209. Immediately, an assistant fire chief left for the call in his private vehicle. Duval stayed behind to co-ordinate the crew, adults and teens alike. One minute later, he had a brush truck on its way. Another minute later, a larger pump truck left.

About the same time, Sharon Duval, Terry’s wife and a labor-and-delivery nurse, received a medical call for the fire. She too left for the scene. The night would be hot, and the men would need fluids to drink—perhaps, but hopefully not, medical attention, too.

For half the run, the volunteers studied the fire—its orange glow lighting the night sky a mile away. Seven, eight minutes later, all the firefighters stood along the tiny road and stared into the blazing, green, grassy area.

A whirling, tornado-like column of flames roared twenty-five feet toward the charcoal heavens and clouded the men’s view. Sun yellow tips of fire licked the trees’ emerald leaves into amber brown. Sweat dripped down the firefighters’ faces.

Duval set up the pumper and radio communication and got everyone in position. The assistant chief led a crew of four down the 170-foot trail to the fire. In the dark, one of them accidentally kicked over a nearly knee-high metal canister as he tried to stretch the 150-foot hose to 170 feet. Quickly, he uprighted the can and sat down on it as he fought the fire.

At 10:10 p.m., Duval called the sheriff’s department and reported a probable stolen vehicle. He knew it wasn’t uncommon for stolen cars and trucks to be dumped in this farmland just a half-hour drive from Austin. He then directed several men onto traffic control. Drizzle coated his body. Smoke was thick and heavy in the humid, night air.

Two firefighters returned from the fire to put on air packs. Five minutes later, the blaze was almost out, and Duval was down at the vehicle. He walked around the perimeter of the 40-foot-wide clearing, staring at a burned-out Jeep with no license plates and no tires.

The tires had melted so that the vehicle rested on its belly. Duval could not see in the dark that one license plate, its right half scorched black, lay on the ground—RHV 33H, the 33H barely readable. A burned compact disc lay a mere half inch or less from the plate. It, too, blended invisibly into the night.

Duval could see that the once green trees above the Jeep were brown from the heat. A trail of rain-dampened grass, burned black, ran from an upside down, five-gallon gas can to the Jeep. It was the same canister the firefighter had overturned earlier.

Near the can was a round, green spot of unburned grass that perfectly matched the circumference of the can. The opened top of the can was burned. The smell of gasoline permeated the wet air, and Duval knew that an accelerant had been used.

He directed two men to stay on the hand line. He was worried there might be a second explosion. The odor of gas was as dense as the wet air. Gas, burned rubber, melted metal—it was a sickening combination of smells.

Duval then took a closer inspection of the vehicle, starting at the burned Jeep’s right-rear corner. Glass crunched under his feet. Duval stopped, having noticed something in the back seat. He ordered the junior firefighters away from the scene and everyone else back forty feet. Only the two men on the hand line were allowed to stay.

Duval had spotted bones, then a skull. He realized a blackened corpse lay in the back seat; it looked like a monkey carved out of cold, hard, black lava. The Jeep, in contrast, was ashen white.

“We have a crime scene here,” Duval said as he called the sheriff’s department a second time. “Step up the response.”

“Want to go down and see the body?” said Duval to his wife.

“No,” said Sharon. She looked around. Everyone seemed to be nervously smoking cigarettes, lots of cigarettes.

Patrol Sergeant John Barton of the Bastrop County Sheriff’s Department arrived and met with Duval. The two men then walked down the trail to the Jeep, a flashlight in Barton’s hand. Barton aimed his light beam and saw the body.

It lay in fetal position, the soft tissue of the head burned completely off. Its shrunken, cooked eyes were at the bottom of the orbital cavities. Its ears were missing. Its arms and legs were jagged stumps. Its chest was distorted, but the full curve of a woman’s breasts was clearly visible.

The men sealed off the area, and Barton phoned the sheriff’s office. “You need to call the Criminal Investigation Division investigator that handles homicide,” he said.

The office called CID investigator Sergeant Don Nelson.

In response to Duval’s first abandoned-vehicle call, two more Bastrop County Sheriff’s officers arrived. Then the sheriff and justice of the peace Katherine K. Hanna arrived. Within twenty to thirty minutes, Nelson was on the scene, and Barton turned the crime over to him.

But in the dark of night, even with lights set up, no one saw the burned, black license plate. Barton located the Jeep’s Vehicle Identification Number—1J4FY49S5SP240535—and called the office via cell phone once again. “Run this number for me.”

Nelson took measurements with Barton, then collected evidence with patrol Deputy Robert Gremillion. Nelson personally filled out an evidence tag for the burned fuel can. He took photographs of the Jeep and the body.

“I need to photograph the underneath,” he said.

They rolled the body over and found tucked beneath the small of its back something that looked to Gremillion like toilet paper. It was scorched cotton cloth, the color blue. Wrapped in the cloth was a single-edged lockblade knife. The knife was unburned, except for one small, scorched, black spot on the wooden handle.

Nelson and two funeral-home workers then tried to remove the body from the back seat, but the crispened corpse crumbled like toast. They were forced to body bag the entire seat, which was only a frame and springs, and the blackened–like–lava corpse. Still, they left a few body parts behind.

Ten a.m., Friday, June 30, 1995, Travis County Chief Medical Examiner Roberto J. Bayardo, M.D. began the post-mortem examination under the written authorization of Katherine K. Hanna, Justice of the Peace, Precinct 3, Bastrop County, Texas.

The partially cremated remains had an estimated height of sixty inches and a residual weight of approximately seventy pounds. The external genitalia were identified as those of a female. The right foot and the lower portion of the right leg were missing. The right hand was completely separated. The back was also extensively charred.

Body X-rays revealed no bullets or broken knives.

There was a one-inch wide stab wound from the soft, front portion of the neck, just above the clavicle, to the fifth rib of the back. The stab track traced a thirty-degree angle, five to six inches deep. It cut through an artery, then a vein, then through the upper lobe of the right lung.

The wound cut the same vessels an undertaker cuts to clean a corpse.

There was a fixed, stainless steel retainer with stainless steel sleeves over the first bicuspid teeth. The retainer was placed in a special envelope, labeled, signed, and saved.

Vaginal smears were negative for sperm.

Dr. Bayardo slit the corpse from the chin to the pubis. In the rib cage, there was the end of the stab wound track. The right pleural cavity was filled with approximately three pints of liquid and clotted blood.

The left leaf of the diaphragm had a one-and-a-half-inch laceration that appeared to be heat-related. Through this laceration the burned base of the diaphragm was protruding.

Only a scanty amount of blood remained in the cardiovascular system.

Both lungs were collapsed. The lower lobe of the left lung was charred and markedly shrunken. The tracheobronchial tree contained a small amount of vomit, as did the upper trachea and larynx.

The woman had been menstruating. A recent corpus luteum was present in the right ovary.

The tip of her tongue was burned.

Her brain had coagulated from the heat, turning into jellylike mush. The blood in her head had drained to the right side.

Alcohol and Valium were present in her blood, and alcohol and cocaine in her bile.

The cause of death, determined Dr. Bayardo, was a stab wound of the neck into the right chest.

Unable to identify the body through fingerprints or any other visual means, the Travis County Morgue sent the corpse to the Bastrop County funeral home.

Jeremy Barnes walked into Regina Hartwell’s apartment to get a pot she had borrowed so that he could cook spaghetti. He also wanted to see how messy the apartment was and how long it would take him to clean it. Barnes, a friend and neighbor of Hartwell’s, often cleaned her apartment to earn extra money.

The place was filthy—beer bottles, empty Marlboro packs, ashtrays overflowing their rims, dirty bathroom, dirty bedroom. What he thought were tampons were on the floor. He didn’t pay much attention to them, though. He knew that Hartwell was having her period and figured her mutt Spirit had pulled them out of the trash.

In the living room, Barnes saw a dark stain on the carpet. Tea, coffee, smeared dog do, he guessed. Regina was a slob. He’d cleaned her apartment enough times to know that. Noticing that Spirit didn’t have any food or water, he filled a soup bowl with water and left.

Anita Morales closed out her last day on the job as an intern for the Austin Police Department. As she drove home on the hot, final Friday of June 1995, she passed Regina Hartwell’s apartment and stared. She and Regina had planned to talk the day before, but they’d never connected despite several pages from Regina and returned calls from Anita. Morales was worried, but she drove on home.

Saturday, July 1, 1995 was a day of more warm temperatures and bright, sunny skies. But Morales and her roommate, Carla Reid, were indoors painting their new apartment, and Carla knew that Anita was distracted. “Regina hasn’t called you back, has she?”

Morales shook her head no.

“Have you tried ... ?” Reid named a litany of friends, all of whom Morales had phoned, none of whom had heard from Hartwell.

Reid dropped her paintbrush and grabbed Morales by the hand. “We’re going over there, now.”

They entered Regina Hartwell’s apartment through a window they both knew had been broken for months. Why they didn’t go through the door, they don’t remember. It was unlocked.

In the doorway, they spotted bloody tissues on the floor. Like Jeremy Barnes, they, too, thought the tissues were tampons Spirit had dragged from the trash. But they didn’t pay much attention to them. They were busy looking for Regina, hoping she hadn’t overdosed or passed out and hit herself on the head.

They glanced at Spirit. The sweet, abandoned mutt didn’t run up to them like she usually did. She cowered in the bedroom.

They went into the living room and flipped on the light. It didn’t work, so they didn’t see the bloodstain on the floor.

Carla Reid went in to Hartwell’s pink and white bathroom. Regina’s makeup and hairbrush were laid out on the counter. She never went anywhere without her makeup and brush.

They walked into the bedroom. All of Hartwell’s clothes were there. All of her shoes were there, except her favorite Doc Martens boots. Her purse was on her bed. It, too, had makeup in it.

“I’m going to check with Jeremy,” said Anita.

She walked over to his apartment and knocked on the door. “Have you seen Regina?”

“No. She called on Thursday and asked me to clean her apartment by Monday.”

Reid was looking through Hartwell’s bills as Morales walked back in, a not-so-faint look of worry across her face.

“Jeremy says Regina told him to clean her apartment by Monday. Maybe she went out of town.” But Anita knew that didn’t ring true, not with Regina’s makeup and purse there.

“But everything’s here,” said Carla.

“Write down every single number that’s on her caller ID,” Morales answered. “Then we’ll start at the top and go all the way down the list and call every number.”

On the list were the numbers of Kim LeBlanc, Kim’s parents, Sean Murphy, Liz Brickman, Hope Rockwell and a Bastrop number. But also on the list were tons of names that Anita and Carla didn’t recognize. It was almost as though Regina had a whole, other life secret from them.

Morales shook her head and pulled out a cigarette (she did that when she was nervous) and socked her hands into her pockets just like her friend Regina did.

Reid phoned Kim LeBlanc. Her number was busy.

She called Liz. Liz said Regina had stood her up Thursday night.

She phoned Sean Murphy. He was out of town.

Anita and Carla dialed Kim’s number again and again. Finally, they went home and back to painting. There seemed to be nothing else to do.

Jeremy Barnes walked over to clean Hartwell’s apartment. He started in the bathroom. He spotted tiny splatters of blood by the commode, tiny splatters of blood on the three walls of the shower—fine, thin splatters as if the blood had been slung on the wall.

But, again, Barnes didn’t think much of it. He knew Hartwell was whacked out on coke these days, that she had blackouts, nosebleeds. He thought about how Regina joked that she did so much cocaine that she could stick her finger up her nose and hit nothing—it’d be hollow.

Other books

El imperio de los lobos by Jean-Christophe Grangé

Darkmoor by Victoria Barry

Burden of Sisyphus by Jon Messenger

Werewolves in Their Youth by Michael Chabon

Kith and Kill by Rodney Hobson

Kev by Mark A Labbe

Wyne and Chocolate (Citizen Soldier Series Book 2) by Michaels, Donna

All For You by Kate Perry

Nothing Lasts Forever by Cyndi Raye

TRAVELLER (Book 1 in the Brass Pendant Trilogy) by Amanda May Bell