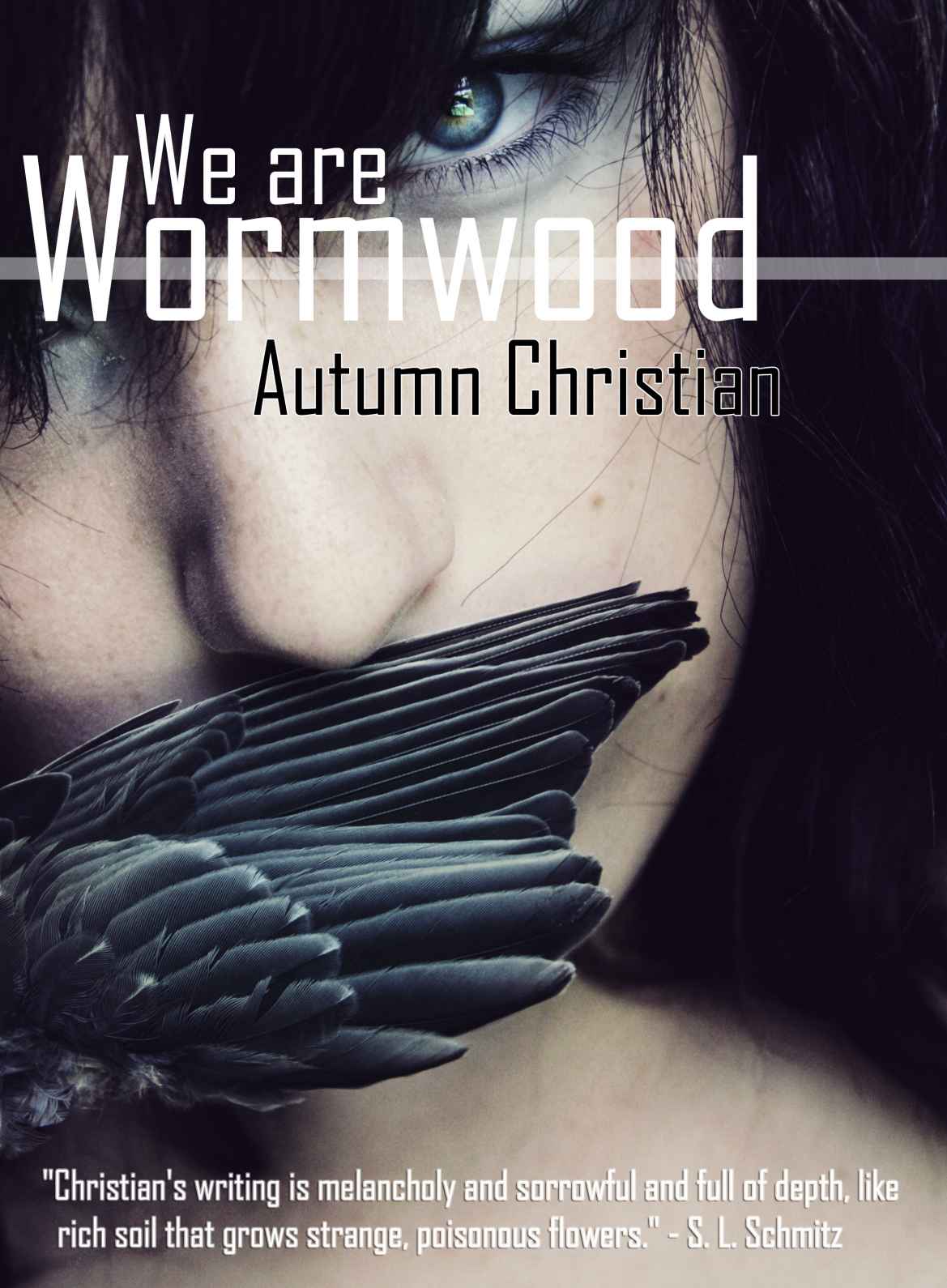

We are Wormwood

Authors: Autumn Christian

WE ARE WORMWOOD

Autumn Christian

Original Photograph by Bailey Elizabeth of

www.baileyelizabeth.com

Cover Design by Janice Duke of

www.janiceduke.com

Copyright © 2013 by Autumn Christian ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places

and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used

fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons living or dead, events, or

locales is entirely coincidental.

Chapter One

A

TINY GOLDEN BEETLE

wriggled through the window and into my eye as I slept.

They'd been coming all week - the beetles, the roly-polies, the spiders -

searching for the way into our house, shimmying, wriggling, and weaving nests.

When I woke, I felt the beetle squirming underneath my eyelid, its filmy wings

fluttering and scraping. It made a small noise, an almost non-noise. Sh. Sh.

Momma must've opened the window when I fell asleep. The oversized curtains hung

across my bed and, in the dark, they looked like limp birds with wings of red

velvet. I rubbed my eye but the beetle wouldn’t come out. I turned on the lamp beside

my bed. Moths rushed in the open window and fluttered around me, against my

lips, crowning my head. The beetle wouldn’t come out.

I ran to Momma’s bedroom, crossing the hallway shimmering

with little slices of moonlight. She was awake, sitting up in her bed amidst

her magic relics and candles, reading a book, plaiting her blonde Scandinavian

hair. Momma never slept. Not when the moon was full. She saw me running down

the hallway and held her arms out to me. She batted the moths away

from

my face. I pointed to my eye, tearing, blinking

frantically.

Momma held me on her lap, trying to extract the beetle,

saying the bugs were thick because the Wormwood star was high in the sky. I

couldn't see it, but it shimmered bright and bitter. Wormwood meant this would

be a year of poison. The insects knew this as the eye of the mad star beat hot

on their backs.

Momma held me still. She said warriors like us knew how to

endure pain better than anyone. She held my eyelids open. The golden beetle

crawled onto my Momma's finger. I told her to kill it or it'd be back again;

she released it on her windowsill where it flew away.

I was six years old, spilling out of her lap, but she

cradled me as she rocked back and forth. Warriors stayed close. We were once

Vikings who rode dragon-headed boats across the ocean, across the ice. We

replaced our flesh with metal to endure the cold and slew creatures others

couldn’t even have nightmares about, but still we loved better than anyone

else. Around campfires, many a story was told

about us and

the monsters that loomed in the dark, quivering in fear at the mention of our

names

. She said, “We will always kill dragons together.”

Later we crept downstairs, Momma holding a votive candle and

a gazelle skull.

“Do you need that skull?” I asked Momma in a quiet voice.

“Shh, baby,” she said. “I’m going to give you a treat.”

On the staircase, a spider furiously wove a web. I wanted to

tear the spider’s web down, because its fingers, thin, like the threads of a

wicker chair, were in my bad dreams. It carried a mark on its back like a

pirate’s skull. Momma told me it only needed a home. Give it this corner of the

universe. I pressed my back against the banister so I wouldn’t have to touch

the web. She laughed, shaking her blonde hair that could’ve been the ruin of

the Vikings. If she’d been born a few centuries earlier, her likeness would

have been a mermaid-figurehead for their ships.

In the kitchen she opened the window above the sink, turned

on the stove, and started to make us hot chocolate. I stood on my tiptoes and

turned on the lights. Roaches with silver feelers skittered away. I swear I

heard them shriek. Momma didn't notice. She was humming, weaving her fingers

through her hair.

“Turn the light off. We’ll dance by candlelight,” she said.

I turned the light off. Her skin was split, honey in

candlelight, powder in moonlight. I climbed up onto the countertop and curled

my toes so the roaches wouldn't scurry across my bare feet; she laughed.

“You've forgotten,” she said, “that you once slew a wolf pup

of the great beast Fenrir. I know when you remember you won't be afraid of

insects anymore.”

I inhaled and I could smell the milk-breath and musky fur of

a wolf. I saw myself in that den, with a silver axe, wrestling the pup. His paw

trapped my hair on the floor. I slew him and wore his pelt as a cloak. There

was a time when I believed that anything Momma said was true.

We drank the hot chocolate together in candlelight and

moonlight. She rested her head in my lap as if she was the child and I the

parent. In order to be a sorceress you have to learn to not sleep. The full

moon recharges you like a battery. You see the shimmer in everything, so you

can pull the thin, magic threads that connected everything and change the

world.

“Drink your hot chocolate, baby, the milk will make you

strong. One day I’ll bring a goat into our backyard. I’ll feed her warm hay and

feed you her milk. You’ll be able to lift six hundred pounds. A thousand. You

could lift a truck if you wanted; you’d be stronger than the strongest person

in the world because you’re not of this world.

Stronger than

Thor.

You should go to bed, baby, you're falling asleep.”

"I'm not tired, I want a story," I said, nodding

off, the drained cup of hot chocolate dangling in my uncurling fingers.

She kissed my forehead, took the cup from my hands, and sent

me upstairs.

A story for another time.

In my bedroom Fiddleback spun a web in my doorjamb. Its

poisonous bite could eat a hole through skin. Ants scurried across the floor,

carrying off droplets of honey. A scorpion clacked around my feet. I might've

once killed a wolf pup, born in mythology, but I never had to deal with

anything like this.

I ran back to tell Momma that I wouldn't sleep until they

were all dead. Halfway down the stairs, I heard the glass votive holder smash

against the wall. I stopped and listened; silence. I leaned over the side of

the railing to try and see Momma, but there was only an open kitchen door and

candlelight piercing the entryway. I crept down the stairs, treading lightly so

the steps wouldn’t creak. Holding my breath, I crossed the light and entered

the kitchen.

Momma wasn’t there. Someone else stood by the kitchen sink

heaving, the gazelle skull tied around her head. Someone else with bleach and

blood oozing from her chewed fingertips. Cockroaches smashed in the sink. She

turned to me with Momma's body, but with the eyes of The Exorcist, eyes like

scratches of lightning.

The Exorcist didn't smell like Momma. She smelled like

antiseptic, like the sour fake smell of lemons and bad magic. A rosary of

powdered bleach ringed her neck. Her eyes were reddened by popped blood

vessels. I wondered if she still had Momma's face underneath the mask, or a

void where a human face once was.

"She's here," Momma said.

She pressed her lips to her mouth and in between grit and

blood-smashed teeth whispered the name.

Nightcatcher. The Nightcatcher's been here.

I grabbed my cup of hot chocolate from the counter. It was

sticky and covered in bleach. She grabbed it out of my hand and tossed it away

in the trash bag at her feet.

“There was poison in the food,” she said.

There was poison in the tap water. Poison on the doorknobs.

Poison in the teacups, on the window latch, in the sunlight, and in the pill

bottles on the countertop. Invisible poison that could not be seen, touched, or

smelled. Poison that would make tongues unravel, bones rot, arms fall off, and

turn a face into a dog's face.

Maybe I only imagined the walls throbbing, trying to squeeze

in on us, but I still couldn’t breathe. The Exorcist flung bleach onto the ants

on the windowsill. She grabbed a broom and rushed past me to the staircase

where she broke the spider's web apart. When the spider tried to flee, she

stomped on it, leaving a black and red smear between her toes.

The shadows were alive; the house was alive and it was

squeezing in on me. A chill followed The Exorcist like a ghost spot. There was

a monster that lived in her skin and wanted to poison us, a monster that not

even Vikings could kill. The Exorcist turned toward me but I knew I couldn't

look into her eyes. Even if she came to protect us from The Nightcatcher and

the poison, those eyes would sear me, burn me, and even kill me. I turned

toward the front door as she touched my shoulder; her hair was screaming, the

air was screaming. I grabbed the doorknob, turned it, and ran onto the lawn

then past the lawn. She called my name and told me to stay inside. Wormwood was

out. I ignored her and ran towards the woods.

It was almost

winter

. The grass

tilted to one side, brown and withered. The trees were skinny and as cold as

lightning rods. The moon hid behind clouds, casting everything into darkness. I

did not see Wormwood in the sky. Momma said it was a small, green star, just

above Mars. If you could drink it, it would taste like cedar.

I reached the edge of the neighborhood where the small woods

lived. I climbed over the barbed wire fence and the "Do Not Enter" sign

protecting the woods, hiking my dress up over my hips so that the hem wouldn’t

catch on the barbs. I thought I felt The Nightcatcher's shadow. She chilled the

air and all stories could be real. I fell on the other side of the fence and stood

up, my arms throbbing.

I ran into the woods. The branches and leaves hid the stars

away. I had been here several times before, but never at night, and never while

shadows pursued me that I thought wanted to eat me alive. I delved further into

the place where the dirt was dark and burnt. In the center of a grove, I found

a hollowed out dead tree once struck by lightning.

It had a mouth like a door. I knelt down

and crawled inside.

In the darkness she reached out and touched my shoulder.

“This is my hiding place,” she whispered.

Even then, when I first heard her speak, I thought that

fangs and rattlers would want to borrow her voice.

“I can’t leave,” I whispered. “Something’s out there. Please

don't make me."

I felt a stirring underneath me, like the earth had begun to

crawl. Then a pungent smell like wet feathers. I pressed my head against the

damp old wood. Her hand slid down my shoulder and touched my palm.

“All right,” she said after a period of silence. “You can

stay.”

I looked up. Her eyes were dark and shiny. Like Wormwood, I

thought. Poison. She sat cross-legged with her knees spread, and in the lap of

her skirt

lay

hundreds of glittering and squirming

roly-polies, spiders, and golden beetles.

"You..."

I tried to say more, but my tongue turned webbed and dry. I

panted softly. She spoke my name.

“Lily.”

The bugs in her lap shone like living crystal. She smiled,

her teeth full of feathers, and touched my cheek.

Then she opened her mouth and made a vociferous noise, a

clacking insect noise.

“Ke-ke-ke-ke.”

I ran.

Chapter Two

BEFORE

THE EXORCIST

came, Momma used to be a professional storyteller. She called

herself Saga, the goddess of storytelling, she who drank from golden cups with

Odin. She carried a magic staff, wore a robe sewn with stars, and told stories

for children in libraries and huge sterile cafeterias. Sometimes I would go

with her and watch with the other children as she read to them from her

Wolf-Book, a tome bound with black fur.

"...And the princess awoke when she heard the thud

underneath her bed. She bolted upright and before the beast could flee, seized

him by the tail. ‘Let me go, let me go,’ the beast pleaded. But the princess

refused to release him until he danced with her.”

Momma was not a writer. She wasn’t born to sit down because

lightning coursed through her and kept her dancing. She made up stories on the

spot - hunters, demons, beasts, and new gods who flew across frozen oceans

– nobody but she and I knew the pages of the Wolf-Book were blank.

As she performed, I watched those bored, wriggling children

become still and listen with rapt attention. She had a different voice for each

character, from the deep-throated growl for the troll’s wife, to a soft,

dream-high voice for the ghost girl. Even Saga, her storytelling persona, spoke

in a husky voice like an ancient codex buried within a queen’s tomb.

"…She did not want to be a princess, she wanted to be a

night girl. Wild girl. And when the priest married her, the new husband’s

cloaks and garments were lifted to find, not the baron the princess’s father

had promised, but the beast that hid underneath her bed. She fled with the

beast to the underworld kingdom, where they lived out their lives in dark and

beautiful wonder.”

She finished her stories with a flourish, then bowed so low

that her robe touched the floor. The children applauded. The teachers always

wanted to ask her, “Where did you get your training?” “Where did you hear that

story?” “Who are you really?”

“A sorcerer never reveals her secrets,” my Momma said with

her hand pressed against her nose, and the children laughed.

Then she swept me up in the whirlwind of her starry robe and

we fled. She often took me out afterwards to eat cheap Italian food, and

sticky, thick caramel milkshakes. As I ate, she leaned over the table and

pushed the hair out of my face. She spoke.

"You don't know this, yet, but when you grow older,

you'll dye your hair a bright red because it's the closest you'll ever feel to

being on fire. You'll fall in love with the ocean because the boys won't be

enough."