What Stays in Vegas (26 page)

Read What Stays in Vegas Online

Authors: Adam Tanner

To deliver ads, Perlich has computers follow what millions of Internet users do, score their behavior, and decide whether to serve them ads on particular topics.

3

This machine-based analysis of vast quantities of data lies at the heart of the fast-growing field of online behavioral advertising. How exactly does Perlich know what anyone is doing on the web, let alone those visiting any one of a hundred million web pages? Through the magic (or, some might say, sorcery) of transparent one-pixel images, sometimes called web beacons, which are embedded into web pages. Such images allow companies like Dstillery to store a

simple file called a cookie on your computer with a random number they have assigned you.

Only the website you are visiting has the ability to save a cookie on your hard drive. If you read the

New York Times

online, only the

NYTimes.com

server can store cookies (unless you set your browser settings to refuse them). If you go to eBay, eBay and perhaps others working with the site will store cookies. The sites will also ask your browser for their own cookies from past visits, but they cannot get access to cookies from other websites.

Dstillery can join the action only if it is working with the website. Then it can look for past cookies it recognizes on your computer and save what is called a third-party cookie. The third-party cookie allows Dstillery to recognize the same browser if the user goes to sites with which the firm has data partnerships, as well as to marketers running ad campaigns with them.

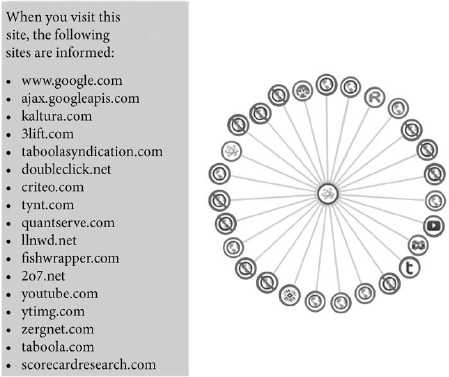

Much like a person looking at the windows of a house across the street, the technology allows Dstillery to see only some of your Internet activity. One might notice the person in the house in front of the right window on the ground floor, then some time later see him pass a window on the opposite end of the house, and then perhaps upstairs. The outsider would not know what the house dweller did between the times he or she passed by these windows. Similarly, Dstillery does not know when Internet users surf to the many sites with which they do not have data-sharing arrangements. But Dstillery can view ten million websites, as if peering into many different buildings with thousands of windows each. Typically, Internet users have no idea what companies are able to see when they visit a page. However, some browser plug-ins allow the data hunted to find out who the data hunters are. For example, a plug-in called disconnect.me shows a series of circles around each website representing ad firms such as DoubleClick, Facebook, and many others. It is often surprising how large this cluster of circles around the site turns out to be.

The cookies allow Dstillery to record the sites you visit until you delete them, something some users never do (although browsers and plug-ins such as disconnect.me allow users to block cookies all the time

if they want). Perlich says her company can reliably track about half the US population that actively uses a desktop or laptop computer, seeing their cookies for an average of ninety days. The company has gathered data showing users looking at a product and perhaps eventually buying, as well as a trail of some of the websites visited beforehand. By analyzing such trends, Dstillery uses predictive modeling to assign scores to every browser in its system. That score, in turn, determines to whom they will try to serve ads and when.

4

Graphical view of all the companies following a user on the site

TMZ.com

. Source: Graphic from browser plug-in disconnect.me (reprinted with permission).

Dstillery also buys tracking data from outside firms, including from a company that provides a popular toolbar that allows people to share content on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, or other sites with just a click. That means that even if Dstillery does not have a direct relationship

with the company operating the website, it can see data on people visiting that site if it has the social toolbar installed there.

Perlich can learn even more about people's patterns of Internet use through the ad networks that her company uses to place advertisements. Dstillery uses real-time bidding (RTB), a process in which companies decide in fractions of a second whether to place an ad targeted to a specific visitor. Dstillery, in effect, asks the RTB network to let the company know when a certain user appears. For example, if that user goes to the

New York Times

website, the RTB asks Dstillery if it wants to bid to place an ad. Even if it doesn't buy an ad, Dstillery has gained new information about that user's pattern of site visits. Dstillery creates a unique twenty-digit number for the people it tracks, but then encrypts the data it gathers so that the information would prove meaningless to outsiders. The company says it does not collect personally identifiable information.

Tracking has become increasingly common in recent years. Many online advertising firms collect information to target their ads, and many well-known firms use web beacons and cookies to gather data on users. Typically they reveal the tracking only in the fine print of their privacy policies, so the process is invisible to almost all users. A sampling of such companies includes Yahoo, Facebook, eBay, HP, American Airlines, Nokia, the Vanguard Group, Microsoft, GE, the New York Yankees, Playboy, Target, Pfizer. Even the Internal Revenue Service makes use of tracking. Also using web beacons are smaller sites such as those of the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission,

rasushi.com

(a chain of sushi restaurants), and

007.com

, the official site of James Bond.

User opinions vary greatly about online tracking, whether through cookies or other means. Some appreciate tracking because it allows advertisers to target messages of interest; others find it sinister. Dstillery CEO Tom Phillips, who cofounded the hip satirical magazine

Spy

in 1986 and later worked for Google to help the company make better use of its data for advertising, scoffs at criticism of targeted ads. He says people make a big fuss over nothing. “Who cares what advertising they

show?” he asks. “What is all of this hullabaloo? It's just advertising, who cares!”

He contrasts online ad targeting with traditional direct marketing, which relies on a person's name, address, and other information. He says such ads, addressed to you by name and delivered by mail, email, or telemarketing, are much more personal than messages coming via the Internet and mobile. With Internet and mobile ads, “they can always clear the cookie, not pay attention to the ad. They can be in control.” In fact, in the short term, the biggest threat to Dstillery and the industry overall came not from public outcry about tracking but from a pattern of deliberate deception that Perlich and other data scientists at the company discovered.

What the Hell's Going On?

Doubts nagged at Perlich. She feared that somehow she had messed up. For months she had noticed patterns of data on her Dell laptop that did not make any sense. Her computers showed a stampede of interest in obscure sites. She feared her computer models had somehow failed, perhaps because they were recording the wrong data. “We found our models doing extremely well, too well for a data scientist's liking,” she said.

Perlich enjoys the freedom to work from home or from the office. She wanted to talk about her doubts to colleague Ori Stitelman, another bespectacled PhD computer whiz, in person. She took the train to the office in Lower Manhattan and arrived at their open work area in front of a massive whiteboard typically filled with mathematical formulas. They reviewed a checklist of potential flaws in their work. Could their models introduce errors as they measured how people navigated the Internet? Then, as Perlich sat in her beloved Ikea Poäng chair, with its curved back and footrest, a flash of intuition seized her. Someone had deliberately created an Internet illusion, hoping to lure money from some of the world's biggest advertisers. She told Stitelman: “This has to be fraud!”

A few days later Stitelman walked past the ping pong table near his desk and climbed the narrow stairwell between the two floors of company headquarters. He set his sights on Andrew Pancer, Dstillery's chief operating officer. To maintain a startup vibe at the young company, Pancer and other executives sit side by side with the rest of the staff, undivided even by cubicles. He looked up and listened as Stitelman and Perlich told him what was on their minds. He reacted sharply. “Oh, shit, there's a problem,” he said. “What the hell's going on?”

5

Within a day the company's management realized that click fraud could jeopardize the very survival of their startup. It was hard enough to explain to companies how online behavioral advertising worked. They feared their clients would flee altogether if they learned that fraud polluted the whole sector.

By following the one-pixel images they had placed on millions of computers, Perlich and Stitelman discovered previously obscure websites scoring remarkably well, suggesting that many people were visiting clusters of these sites before moving on to better-known retail sites. Their models showed thousands of websites they had never heard of, including

Iamcatwalk.com

,

6

therisinghollywood.com

,

7

parentingnews.com

,

8

and

womenshealthspace.com

,

9

scoring better than any other sites, representing a sort of online stampede to unknown pastures. Such patterns ordinarily would suggest that companies should place their ads where the stampede was taking place.

But were these ghost visitors? The people visiting many of these websites seemed to have utterly unconnected interests. Of those who visited

parentingnews.com

, 80 percent would also go to

ChinaFlix.com

.

10

“Why would all these parents want to watch Chinese videos?” Perlich wondered. Then ChinaFlix would send heavy traffic to well-known websites such as

chase.com

or

nike.com

. Could it be that people visiting

ChinaFlix.com

were much more likely to apply for a credit card or buy running shoes and pizza than other Internet users?

The data scientists tried to figure out the relationship between the different sites and found that many visitors were going from one to another in fractions of secondsâat speeds that were impossibly fast. The traffic was automated somehow. It was mechanized, not human. Stitelman, who earned his doctorate in biostatistics in 2010 at the University of California, Berkeley, worked until late in the night to try to understand what was happening.

Claudia Perlich at work. Source: Author photo.

In some cases, Perlich and Stitelman detected patterns in which a cookie traveled back and forth among seven hundred websites for a millisecond each, suggesting that a single Internet user had clicked to different pages ten thousand times in one day. The heavy traffic among the sites made them seem like key nodes on which to advertise.

Click fraud presented a dilemma for a firm competing in a tough business.

Overall, the new sites represented as much as a fifth of the total inventory of some online advertising networks, meaning that a fair chunk of advertising did not encounter humans at all. Although the data scientists had produced some scientifically fascinating results, their findings pleased nobody. They meant Dstillery, as well as its online advertising rivals, were sometimes buying ads that no one would ever view.

If Dstillery quietly cleaned up its models to avoid the suspect networks, rivals might show better numbers in delivering ads to wider audiences. The executives were unsure how to react. Across the online advertising ecosystem, people made money by not rocking the boat.

Stitelman said some media buyers at companies buying the ads asked them to turn the click fraud back on after they learned what had happenedâtheir numbers looked worse without the fraudulent hits. Without the numbers, their annual bonuses could suffer. “The sad thing is that everyone is incentivized to sort of ignore it,” he says. “Even though we know it's all fake! I don't know how people look in the mirror.”