When All Hell Breaks Loose (66 page)

Read When All Hell Breaks Loose Online

Authors: Cody Lundin

"Anthra!" [Translation: "Fire!"]

—Quest for Fire

, the movie

L

ight is a form of energy, which can be emitted through a variety of processes including incandescence, fluorescence and phosphorescence, and laser generation. According to anthropologists, incandescence in the form of the element fire has been manipulated by someone or something for more than 2.5 million years. For indigenous peoples the world over, this flickering delight had limitless uses. It cooked food, disinfected water, made tools and weapons, regulated body temperature, and kept wild critters at bay. Nevertheless, one of the more profound and lasting attributes that fire could gift a growing world was the promise of light for the night. From coast to coast and culture to culture, humanity's aboriginal lighting was a simple by-product of one of nature's four sacred elements.

All flame-type lighting devices produce gases, which when burned feed the flame. Stuff that was burned for light over the centuries was incredibly varied and included pine pitch, birch bark, and the oils and fats from a number of animals, fish, and plants.

In Ice Age Europe nearly 40,000 years ago, the invention of stone, fat-burning lamps heralded the first effective, portable means of exploiting this aspect of fire. So profound was this shift in technology that it coincided with other remarkable changes in culture including the emergence of art, personal adornment, and complex weapons systems.

In the 1600s, early colonial settlers in America made candles just like the Indians taught them: from sections of conifer trees (pitch wood) that were cut into segments and burned. Later on, folks wanted to burn larger and larger things for brighter light. A container was devised, called a

cresset

or fire basket, that was nothing more than a noncombustible containment device made from clay, stone, or metal.

Cressets, although not designed for burning liquid fuels, were amazing as now people could light streets, the decks of boats, and more. Using the fat-lamp concept, people started making all sorts of lamps and lanterns from clay, metal, stone, shells, and glass—anything that was liquid-worthy and could thus be filled with burnable oils such as olive oil, fish oil, whale oil, or sesame oil, among others. This light source had a wick made from dried moss, plant fibers, fabric—almost anything that would conduct the fuel to the flame. The wick could be adjusted as needed for more or less light, thereby conserving precious fuel.

Lighting technologies rapidly advanced and changed through the centuries from coal oil and camphene to kerosene and paraffin. From 1800 to 1850 alone, more than five hundred patents were granted for improvements in lighting devices.

In the 1850s, kerosene lighting was largely replaced by natural gas, which was in turn replaced by electricity in the 1880s. As the world rockets into the twenty-first century, who knows what lighting method will replace our current standard?

A Bump in the Night

Within every twenty-four-hour cycle on our planet, with few exceptions, we can all count on standing in the dark for several hours. For the past few decades, however, the vast majority of towns and cities have covered up this fact with a barrage of artificial lighting. Urbania's addiction to lighting, and the ease with which this addiction can be pacified, cause many people on the grid to think about lighting only when they don't have it. Lighting has become common enough to be completely taken for granted. Entire neighborhoods, towns, and cities sprout a blinding array of 24/7 indoor and outdoor lighting, literally blotting out the nighttime sky and any hope for seeing what grandma used to call stars. Many urban areas are so well-lit that darkness, and the psychological learning that comes along with it, never happens.

Few modern people have the psychological stamina to deal with life's burdens and fears when the lights go out. They have never trained or even considered what to do when it's pitch black. This complacency has worked its way into our psyches to a point that, when the darkness finally comes due to a power outage or other means, many of us feel helpless and lost. Don't believe me? Venture into the woods with me on one of my wilderness courses where I don't allow artificial lighting of any kind. Time after time, I have witnessed countless people become hopelessly confused and humbled when darkness descends upon the camp. And the majority of these people have a good degree of outdoor experience.

Adequate lighting not only comes in handy when trying to find the canned beans during a power outage, but it is also vital for long-term sanity. Several studies regarding the proper design and use of underground nuclear fallout shelters all came to the conclusion that people go nuts when subjected to continuous, long-term darkness. The good news is that very low levels of light, in which a simple outline of a human form is all that can be distinguished, will prevent the crazies. Total pitch blackness, the kind where you are unable to see your hand in front of your face, is the kind of darkness that's the most difficult to deal with, especially if you have other people freaking out in your proximity. While holing up underneath the petunias in the backyard is off-focus for the intention of this book, becoming familiar with the ins and outs of emergency lighting, especially during low-light winter months, is not. Luckily for us savvy survivors there are several gadgets on the market that light up the night with little effort.

Let There Be Light! Banishing Fright from the Night

Fantastic Flashlights

The first flashlight was invented in the 1890s by Conrad Hubert, founder of the Eveready Battery Company. The lighting device got its name because at that time the batteries were not strong enough to power the light for a sustained amount of time, thus the user had to literally "flash light" for a moment in front of himself in order to conserve power. Early commercial flashlights started as a novelty and consisted of a small light, which was attached to a man's tie or a woman's barrette. It was necessary at the time to carry a large battery pack, which was sure to have been a buzz kill regardless of the cool gadget attraction.

Although all households in the modern world have a flashlight or two in their midst, odds are the batteries haven't been replaced since the 1990s. Being able to see in the dark is a gift. Flashlights have saved me more than once from having to spend an unplanned night out in the wilderness, and I use them regularly at home. In fact, there's a flashlight situated at virtually every entrance to my house.

There is little substitute for a high-quality flashlight. Even so, I have witnessed supposedly worthy lights take a dump on their owners at compromising times. There are many flashlight shapes and sizes available, although the AA-battery-size flashlights are typically cheap, compact, widely available, and have enough candlepower to get the job done for the lion's share of household chores. In addition to the AA variety, I recommend that you consider the larger C- or D-cell-size flashlights as well. Having one or two of these around the house will really light up your life; some are extremely bright for larger nighttime jobs or backyard missions where extra light is advisable. As a side note, most airborne Search and Rescue teams use night-vision equipment during their missions. Night vision makes a small AA flashlight look like a truck with its high beams on. To give your rescuers the best visibility possible, sweep the flashlight beam from side to side of where you are; don't point it at the pilot.

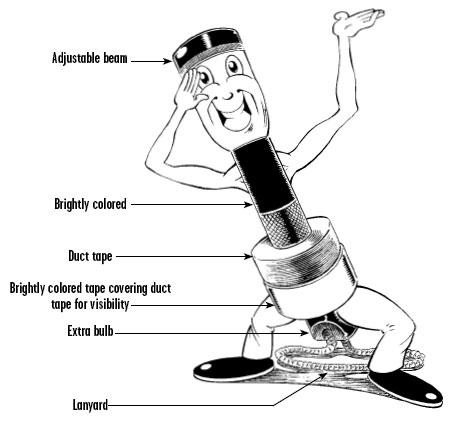

Choose the most dependable, widely available, brightly colored flashlight possible or make it that way with brightly colored tape. We are a visually oriented culture so making your preparedness gear strikingly obnoxious is a bonus. My AA flashlight has duct tape wrapped around the end as a bite piece. I often hold my flashlight in my mouth thereby freeing up my hands for various tasks, and teeth and aluminum don't mix. The hundreds of uses for the extra duct tape speak for itself. At the end of my light is a lanyard that allows me to secure it to my wrist. The lanyard is necessary in situations that might physically separate me from my light such as violent storms, flooding, deep snow, or heavy brush. The flashlight I carry is widely available, cheap, has reasonably priced, easy-to-obtain spare bulbs, stores a spare bulb in its end cap, and has an adjustable beam. Flashlights are reasonably kidproof and should be high on the list for families with children.

The Wild World of Specialty Flashlights

I shy away from specialty flashlights if for no other reason than the spare parts and bulbs are a pain to find on a good day, let alone during the end of the world. I want to be able to replenish my stock with a minimum of hassle and most of us don't need much of an excuse to procrastinate buying, repairing, or rotating emergency supplies. Some flashlights are so powerfully bright that they could almost cause sunburn, to say nothing of what they could do to your eyesight. I do admire their brightness but that strong light comes at a price, literally and figuratively; these flashlights eat batteries like a politician hugs babies during an election year. I have no interest in paying for, storing, and feeding these types of lights for daily household use. Analyze your situation and see if one of the bright boys fits in with your survival plan.