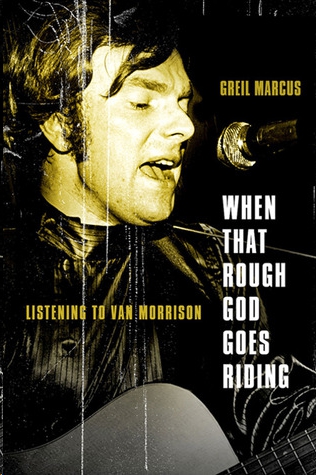

When That Rough God Goes Riding

Read When That Rough God Goes Riding Online

Authors: Greil Marcus

Table of Contents

Praise for

When That Rough God Goes Riding

When That Rough God Goes Riding

“Writing about the songs of Van Morrison is rightly seen as something of a paradox. Perhaps that’s because, for all his scholarly use of multiple musical styles and his reference to Yeats and Joyce, the Belfast Cowboy’s work is more sensual than it is intellectual. Which makes the renowned rock critic Greil Marcus, who’s written definitively on Elvis and Bob Dylan, the right man to plumb that work. Combining an incantatory prose style with careful reporting and inventive, sometimes infuriating judgments, Marcus manages to illuminate Morrison’s cerebral soul music—even if, as the singer once claimed, ‘the process is beyond words.’”

—PETER GERSTENZANG,

New York Times Book Review

New York Times Book Review

“No critical testimonial is more welcome than this assessment of Morrison’s work by one of America’s most astute cultural critics.... Marcus is informed and insightful. Particularly illuminating are his observations on the tensions between Morrison’s roles as singer and songwriter, and on Morrison’s ongoing ‘quest for the yarragh’—fleeting, elusive moments of transcendence. Morrison’s volatile idiosyncrasy and diverse

oeuvre

make his career difficult to appraise, but Marcus convinces us of its singular importance.”

oeuvre

make his career difficult to appraise, but Marcus convinces us of its singular importance.”

—GORDON FLAGG,

Booklist

Booklist

“[Marcus is] literate, brainy, and fearless in making cross-genre comparisons.”

—JEFF BAKER,

Portland Oregonian

Portland Oregonian

“Written in prose as free-associative as the music it concerns,

When That Rough God Goes Riding

derives energy from the fact that Marcus was present at many of the landmark moments he’s exegizing.”

When That Rough God Goes Riding

derives energy from the fact that Marcus was present at many of the landmark moments he’s exegizing.”

—TED SCHEINMAN,

Washington City Paper

Washington City Paper

“

When That Rough God Goes Riding

explores moments of contradiction, sublime beauty, audacity, failure, and grace in the singer-songwriter’s career with a keen ear, weaving the rich thoughtfulness we’ve come to expect from one of America’s best cultural critics and historians into an elegantly structured series of staccato essays which reveal Marcus’ fascination with Van Morrison’s music.”

When That Rough God Goes Riding

explores moments of contradiction, sublime beauty, audacity, failure, and grace in the singer-songwriter’s career with a keen ear, weaving the rich thoughtfulness we’ve come to expect from one of America’s best cultural critics and historians into an elegantly structured series of staccato essays which reveal Marcus’ fascination with Van Morrison’s music.”

—ROBERT LOSS,

Popmatters.com

Popmatters.com

“This is the book that Van Morrison’s artistry has long deserved, and The Man’s devotees will celebrate its blend of eloquence, passionate scholarship and soulfulness. [

When That Rough God Goes Riding

] superbly fulfills criticism’s primary function: It sends you for the first or 100th time to the works of art on which it muses, better equipped to experience what’s always been there.”

When That Rough God Goes Riding

] superbly fulfills criticism’s primary function: It sends you for the first or 100th time to the works of art on which it muses, better equipped to experience what’s always been there.”

—

JON REPP,

Cleveland Plain-Dealer

JON REPP,

Cleveland Plain-Dealer

“[Marcus’] ability to couple shrewd music criticism, historical perspective, and broader genre analysis makes his work an adventurous read.... Marcus doesn’t attempt to tidily summarize Morrison’s life and career, but he does provide plenty of thought-provoking insights into this enigmatic performer, and his slipstream of references results in a fascinating meditation on Morrison’s oeuvre. You wind up wanting to pull out and listen to your Morrison albums and hunt down the many bootleg recordings that Marcus references here, searching for that elusive yarragh.”

—

MICHAEL BERICK

, San Francisco Chronicle

MICHAEL BERICK

, San Francisco Chronicle

“Marcus is a smart respite from the raging stupidity and antiintellectualism on every front, and yet knows how to have rock ‘n’ roll fun at the same time.”

—

MICHAEL SIMMONS,

LA Weekly

MICHAEL SIMMONS,

LA Weekly

For Dave Marsh

NORTHERN MUSE. GREEK THEATRE, BERKELEY. 3 MAY 2009

The fourteen-piece

band assembled for a concert in which Van Morrison was to perform the whole of his forty-oneyear-old album

Astral Weeks

so dominated the stage you might not have even noticed the figure seated at the piano; the sound Morrison made when he opened his mouth seemed to come out of nowhere. It was huge; it silenced everything around it, pulled every other sound around it into itself—Morrison’s own fingers on the keys, the chatter in the crowd that was still going on because there was no announcement that anything was about to start, cars on the street, the ambient noise of the century-old open-air stone amphitheatre, where in 1903 President Theodore Roosevelt spoke, where in 1906 Sarah Bernhardt appeared to cheer on San Francisco as it dug out of its ruins, where in 1964 the student leader Mario Savio rose to speak to the

whole of the university gathered in one place and was seized by police the instant he stood behind the podium as the crowd before him erupted in screams, where Senator Robert F. Kennedy spoke in 1968, days before he was shot. The first word out of Morrison’s mouth that night, if it was a word, not just a sound, something between a shout and a moan, was, you could believe, as big as anything that ever happened on that stage.

band assembled for a concert in which Van Morrison was to perform the whole of his forty-oneyear-old album

Astral Weeks

so dominated the stage you might not have even noticed the figure seated at the piano; the sound Morrison made when he opened his mouth seemed to come out of nowhere. It was huge; it silenced everything around it, pulled every other sound around it into itself—Morrison’s own fingers on the keys, the chatter in the crowd that was still going on because there was no announcement that anything was about to start, cars on the street, the ambient noise of the century-old open-air stone amphitheatre, where in 1903 President Theodore Roosevelt spoke, where in 1906 Sarah Bernhardt appeared to cheer on San Francisco as it dug out of its ruins, where in 1964 the student leader Mario Savio rose to speak to the

whole of the university gathered in one place and was seized by police the instant he stood behind the podium as the crowd before him erupted in screams, where Senator Robert F. Kennedy spoke in 1968, days before he was shot. The first word out of Morrison’s mouth that night, if it was a word, not just a sound, something between a shout and a moan, was, you could believe, as big as anything that ever happened on that stage.

INTRODUCTION

In 1956

, the stiff and tired world of British pop music was turned upside down by Lonnie Donegan’s “Rock Island Line,” a skiffle version of a Lead Belly song, played on guitar, banjo, washboard, and homemade bass. Like thousands of other teenagers, John Lennon put together his own skiffle band in Liverpool that same year; Van Morrison, born George Ivan Morrison in 1945 in East Belfast, in Northern Ireland, formed the Sputniks in 1957, the year the Soviet Union put the first satellite into orbit and John Lennon met Paul McCartney. Morrison would never find such a comrade, and, unlike the Beatles, he would never find his identity in a group. Whether in Ireland, England, or the United States, he would always see himself as a castaway.

, the stiff and tired world of British pop music was turned upside down by Lonnie Donegan’s “Rock Island Line,” a skiffle version of a Lead Belly song, played on guitar, banjo, washboard, and homemade bass. Like thousands of other teenagers, John Lennon put together his own skiffle band in Liverpool that same year; Van Morrison, born George Ivan Morrison in 1945 in East Belfast, in Northern Ireland, formed the Sputniks in 1957, the year the Soviet Union put the first satellite into orbit and John Lennon met Paul McCartney. Morrison would never find such a comrade, and, unlike the Beatles, he would never find his identity in a group. Whether in Ireland, England, or the United States, he would always see himself as a castaway.

East Belfast was militantly Protestant, but Morrison’s parents were freethinkers; even after his mother became a Jehovah’s Witness for a time in the 1950s, his father remained a

committed atheist. The real church in the Morrison household was musical. There was always the radio (“My father was listening to John McCormack”); more obsessively, there was “my father’s vast record collection,” 78s and LPs by the all-American Lead Belly, and within the kingdom of his vast repertoire of blues, ballads, folk songs, protest songs, work songs, and party tunes that dissolved all traditions of race or place, the minstrel and bluesman Jimmie Rodgers, cowboy singers of the likes of Eddy Arnold and Gene Autry, the balladeer Woody Guthrie, the hillbilly poet Hank Williams, the songsters Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, the gospel blues guitarist Sister Rosetta Tharpe—and later Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Little Walter, John Lee Hooker, Big Joe Williams, all of them magical names. Thus when the thirteenyear-old singer, guitar banger, and harmonica player Van Morrison went from the Sputniks to Midnight Special, named for one of Lead Belly’s signature numbers—and after that from Midnight Special to the Thunderbolts, a would-be rock’n’ roll outfit that tried to catch the thrills of Jerry Lee Lewis and Little Richard, and from the Thunderbolts to the Monarchs Showband, a nine-man outfit with a horn section, choreographed shuffles, and stage suits that would play your company dinner, your Christmas party, your wedding, and which in the early ’60s toured Germany offering Ray Charles imitations to homesick GIs, only a patch of the map Morrison carried inside himself had been scratched.

committed atheist. The real church in the Morrison household was musical. There was always the radio (“My father was listening to John McCormack”); more obsessively, there was “my father’s vast record collection,” 78s and LPs by the all-American Lead Belly, and within the kingdom of his vast repertoire of blues, ballads, folk songs, protest songs, work songs, and party tunes that dissolved all traditions of race or place, the minstrel and bluesman Jimmie Rodgers, cowboy singers of the likes of Eddy Arnold and Gene Autry, the balladeer Woody Guthrie, the hillbilly poet Hank Williams, the songsters Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, the gospel blues guitarist Sister Rosetta Tharpe—and later Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Little Walter, John Lee Hooker, Big Joe Williams, all of them magical names. Thus when the thirteenyear-old singer, guitar banger, and harmonica player Van Morrison went from the Sputniks to Midnight Special, named for one of Lead Belly’s signature numbers—and after that from Midnight Special to the Thunderbolts, a would-be rock’n’ roll outfit that tried to catch the thrills of Jerry Lee Lewis and Little Richard, and from the Thunderbolts to the Monarchs Showband, a nine-man outfit with a horn section, choreographed shuffles, and stage suits that would play your company dinner, your Christmas party, your wedding, and which in the early ’60s toured Germany offering Ray Charles imitations to homesick GIs, only a patch of the map Morrison carried inside himself had been scratched.

In 1964, in Belfast, with the band Them, Morrison began to find his style: the blues singer’s marriage of emotional extremism and nihilistic reserve, the delicacy of a soul singer’s presentation of a bleeding heart, a folk singer’s sense of the

uncanny in the commonplace, the rhythm and blues bandleader’s commitment to drive, force, speed, and excitement above all. The group’s name, calling up the 1954 horror movie about giant radioactive ants loose in the sewers of Los Angeles, was full of teenage menace:

ran ads in the Belfast

ran ads in the Belfast

Telegraph

. With Morrison pushing the combo through twenty minutes of his own “Gloria,” night after night in the ballroom of a seamen’s mission called the Maritime Hotel, Them began to live up to its name.

uncanny in the commonplace, the rhythm and blues bandleader’s commitment to drive, force, speed, and excitement above all. The group’s name, calling up the 1954 horror movie about giant radioactive ants loose in the sewers of Los Angeles, was full of teenage menace:

Telegraph

. With Morrison pushing the combo through twenty minutes of his own “Gloria,” night after night in the ballroom of a seamen’s mission called the Maritime Hotel, Them began to live up to its name.

Cut to three minutes or less on 45s, the band’s songs would soon bring Morrison a taste of fame. In 1965, in London—“Where,” the liner notes to Them’s second album quoted Morrison, “it all happens! ...”—the group crumbled, but Morrison recorded under their name with a few members of the band and a clutch of studio musicians. Though Morrison would disavow them as the most paltry reductions of what had happened at the Maritime—“It wasn’t even Them after Belfast,” Morrison told me one afternoon in 1970, as he told others before and since—Them made two unforgettable albums, harsh in one moment,

lyrical in the next. In 1965 and 1966 Them scored modest hits on both sides of the Atlantic: “Gloria” (covered by the Chicago band the Shadows of Knight, who had the bigger hit in the U.S.A., except on the West Coast), “Here Comes the Night,” “Baby Please Don’t Go,” “Mystic Eyes.”

lyrical in the next. In 1965 and 1966 Them scored modest hits on both sides of the Atlantic: “Gloria” (covered by the Chicago band the Shadows of Knight, who had the bigger hit in the U.S.A., except on the West Coast), “Here Comes the Night,” “Baby Please Don’t Go,” “Mystic Eyes.”

To those who were listening, it was clear that Van Morrison was as intense and imaginative a performer as any to have emerged in the wake of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones—who, he claimed of the latter band in angry, drunken moments, stole it all from him, from

him

! Yet it was equally clear, to those who saw Them’s shows in California in 1966—at the Fillmore Auditorium in San Francisco, and at the Whisky A-Go-Go in Los Angeles in 1966, where the group headlined over Captain Beefheart one week and the Doors the next—that Morrison lacked the flair for pop stardom possessed by clearly inferior singers, Keith Relf of the Yardbirds, Eric Burdon of the Animals, never mind Mick Jagger, who in those days were seizing America’s airwaves like pirates, if not, as with Freddie and the Dreamers or Wayne Fontana and the Mindbenders, conning the nation’s youth like the King and the Duke bamboozling Huck and Jim. Morrison communicated distance, not immediacy; bitterness, not celebration. His music had power, but too much subtlety for its power not to double back into fear, loss, fury, doubt.

him

! Yet it was equally clear, to those who saw Them’s shows in California in 1966—at the Fillmore Auditorium in San Francisco, and at the Whisky A-Go-Go in Los Angeles in 1966, where the group headlined over Captain Beefheart one week and the Doors the next—that Morrison lacked the flair for pop stardom possessed by clearly inferior singers, Keith Relf of the Yardbirds, Eric Burdon of the Animals, never mind Mick Jagger, who in those days were seizing America’s airwaves like pirates, if not, as with Freddie and the Dreamers or Wayne Fontana and the Mindbenders, conning the nation’s youth like the King and the Duke bamboozling Huck and Jim. Morrison communicated distance, not immediacy; bitterness, not celebration. His music had power, but too much subtlety for its power not to double back into fear, loss, fury, doubt.

What he lacked in glamour he made up in strangeness—or rather his strangeness made glamour impossible, and at the same time captivated some who felt strange themselves. Morrison never covered Randy Newman’s “Have You Seen My Baby?”—“I’ll talk to strangers, if I want to / ’Cause I’m a

stranger, too”—he didn’t have to. He was small and gloomy, a burly man with more black energy than he knew what to do with, the wrong guy to meet in a dark alley, or backstage on the wrong night. He didn’t fit the maracas-shaking mode of the day. Instead, in 1965, he recorded a ghostly version of “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” that outran Bob Dylan’s original, and then turned the fey Paul Simon rewrite of Edward Arlington Robinson’s 1897 poem “Richard Cory” into a bone-chilling fable of self-loathing and vengefulness.

stranger, too”—he didn’t have to. He was small and gloomy, a burly man with more black energy than he knew what to do with, the wrong guy to meet in a dark alley, or backstage on the wrong night. He didn’t fit the maracas-shaking mode of the day. Instead, in 1965, he recorded a ghostly version of “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” that outran Bob Dylan’s original, and then turned the fey Paul Simon rewrite of Edward Arlington Robinson’s 1897 poem “Richard Cory” into a bone-chilling fable of self-loathing and vengefulness.

Other books

Game of Death by David Hosp

Luminosity by Thomas, Stephanie

The Inquisitor by Peter Clement

The Search by Shelley Shepard Gray

My Lucky Groom (Summer Grooms Series) by Baird, Ginny

Wild Roses by Deb Caletti

Papelucho by Marcela Paz

Death Without Company by Craig Johnson

Post-Human Series Books 1-4 by Simpson, David

Love and Gravity by Connery, Olivia