Which Way to the Wild West? (2 page)

Read Which Way to the Wild West? Online

Authors: Steve Sheinkin

A

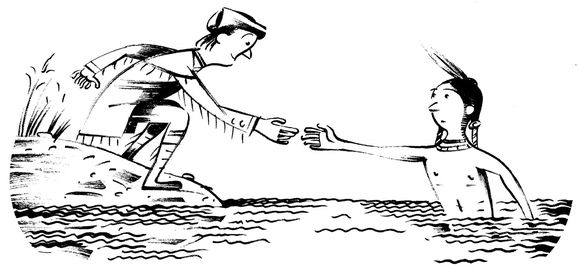

few months later, three Lakota Indian boys were swimming in the Missouri River in what is now South Dakota. They noticed a group of about thirty men setting up tents on the other side of the river. The boys had seen a few white men before (though never a black man). But they had never seen a large group like this. They swam across the river to investigate.

few months later, three Lakota Indian boys were swimming in the Missouri River in what is now South Dakota. They noticed a group of about thirty men setting up tents on the other side of the river. The boys had seen a few white men before (though never a black man). But they had never seen a large group like this. They swam across the river to investigate.

Though they couldn't understand each other's words, the Lakota boys and the travelers were able to communicate pretty well using sign language. The leaders of the white men seemed to be saying that they wanted to meet with the Indian chiefs. The boys told them to come to their nearby village, and pointed out the way.

Two days later the travelers paddled up to the village. The chiefs welcomed them, and the groups traded food as a symbol of goodwill. Then the Lakota people gathered around to listen to one of the white leaders, who began a speech with the words:

“Blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah blah ⦔

At least, that's what it must have sounded like to the Lakota. To those who spoke English, it was clear that Lewis was explaining that all of this land now belonged to the United States. From now on, Lewis said, Native Americans of the region must obey the commands of the “Great Chief”âPresident Jefferson, that is.

“The Great Chief of the seventeen great nations of America has become your only father,” Lewis said. “He is the only friend to whom you can now look for protection, or from whom you can ask favors, or receive good councils, and he will take care that you shall have no just cause to regret this change.”

Meriwether Lewis

No cause to regret the change? Well, we'll see about that.

Meanwhile, Lewis realized that the Lakota had no clue what he was saying. One of Lewis's men was trying to translate the speech using sign language. It wasn't working. “We feel much at a loss for the want of an interpreter,” Clark noted.

So Lewis stopped talking. Instead, he had his men put on their fancy army uniforms and parade back and forth, firing their guns. Then Lewis and Clark gave out gifts to the chiefsâeach one got a “peace medal” with an image of President Jefferson

on one side and an Indian and a white man shaking hands on the other.

on one side and an Indian and a white man shaking hands on the other.

The reaction of the Lakota chiefs was basically

That's it? You're asking to pass through our territory, and all you offer in exchange is a stupid medal?

They wanted useful tools, and guns and ammunition.

That's it? You're asking to pass through our territory, and all you offer in exchange is a stupid medal?

They wanted useful tools, and guns and ammunition.

Both sides were annoyed. Both sides were frustrated by their inability to communicate. When three Lakota warriors grabbed one of Lewis and Clark's boats, the situation nearly exploded. The Indians and Americans shouted threats at each other. “I felt myself warm and spoke in very positive terms,” Clark remembered.

Clark pulled out his sword and ordered his men to aim their guns. The Lakota warriors raised their own weapons. “Most of the warriors appeared to have their bows strung and took out their arrows from the quiver,” said Clark.

For several tense seconds the two groups stood fifty feet apart, weapons aimed at each other. Anything could have happenedâthough if shooting started, the badly outnumbered Corps of Discovery would almost certainly have been wiped out. Finally, a Lakota chief named Black Buffalo stepped between the men and convinced his warriors to lower their bows.

Then the Corps of Discovery continued their journey west.

L

ewis and Clark had a much better time at the Mandan and Hidatsa villages they reached the following month. They were given food and information about the route ahead. Most important, this is where they met a sixteen-year-old Shoshone woman named Sacagawea.

ewis and Clark had a much better time at the Mandan and Hidatsa villages they reached the following month. They were given food and information about the route ahead. Most important, this is where they met a sixteen-year-old Shoshone woman named Sacagawea.

About four years before, Hidatsa warriors had raided a Shoshone

village and kidnapped Sacagawea. They then sold her to a Canadian fur trader named Toussaint Charbonneau. He considered her his wife (though technically he already had one).

village and kidnapped Sacagawea. They then sold her to a Canadian fur trader named Toussaint Charbonneau. He considered her his wife (though technically he already had one).

Now Charbonneau came to Lewis and made an offer: Hire me and Sacagawea as interpreters. Lewis didn't really want Charbonneau (he called the fur trapper “a man of no particular merit”), but he did think Sacagawea's knowledge of the Shoshone language would be helpful. Lewis hoped to meet up with the Shoshone in the Rocky Mountains, and he would need their knowledge of the local geography. So he agreed to hire the husbandand-wife team (all the money went to the husband).

On a freezing morning in February 1805, Sacagawea gave birth to a baby boy, Jean Baptiste. Less than two months later, she strapped the baby on her back and headed west with the Corps of Discovery.

As Lewis had feared, Charbonneau was not too helpful. He kept accidentally tipping over the boats, dumping precious supplies into the river. Sacagawea proved to be much more useful, finding edible roots and berries where no one else would have known to look.

Sacagawea

By the time the crew climbed into the Rocky Mountains in August, the men were hungry and exhausted. And lost. Luckily for the Corps, Sacagawea had grown up around there. “The Indian woman recognized the point of a high plain to our right, which she informed us was not very distant from the summer retreat of her nation,” wrote Lewis.

Sure enough, Lewis soon spotted a Shoshone man on a horse, about two hundred yards away. “I now called to him in as loud a voice as I could command,” said Lewis, “repeating the word

tab-ba-bone,

which in their language signifies âwhite man.'”

tab-ba-bone,

which in their language signifies âwhite man.'”

The Shoshone rider took one look at this group of armed men coming toward him shouting “White man!” He turned his horse and raced away.

The Americans spent the next few days desperately searching for the Shoshone camp. Lewis kept spotting single Shoshone at a distance and then calling out,

“Tab-ba-bone! Tab-ba-bone!”

And they kept riding away.

“Tab-ba-bone! Tab-ba-bone!”

And they kept riding away.

Finally the Corps found the camp. Standing there waiting for them were sixty Shoshone warriors. Lewis did a smart thingâhe set his rifle on the ground.

The Shoshone then strode toward Lewis, saying,

“Ah-hi-e, ah-hi-e.”

Lewis was quite confused, until the chief put his arm around Lewis's shoulder and touched his cheek to Lewis's cheek. That seemed like a good sign. (Lewis learned later that

“Ah-hi-e”

means “I am much pleased.”)

“Ah-hi-e, ah-hi-e.”

Lewis was quite confused, until the chief put his arm around Lewis's shoulder and touched his cheek to Lewis's cheek. That seemed like a good sign. (Lewis learned later that

“Ah-hi-e”

means “I am much pleased.”)

Sacagawea began to interpret between Lewis and the chief. But she kept stopping to stare at the chief's familiar face. She suddenly realized that this was Cameahwait, her long-lost big brother! “She

jumped up and ran and embraced him,” Lewis wrote. Sacagawea had not shown the tiniest bit of emotion in the months Lewis had known her. Now, as she interpreted between her brother and Lewis, she kept bursting out in tears of joy.

jumped up and ran and embraced him,” Lewis wrote. Sacagawea had not shown the tiniest bit of emotion in the months Lewis had known her. Now, as she interpreted between her brother and Lewis, she kept bursting out in tears of joy.

T

hanks largely to Sacagawea, the Shoshone gave Lewis and Clark advice about how to cross the mountains, and horses to carry their goods. The Corps continued west, making it all the way to the Pacific coast by November 1805. Here Clark wrote his famous line:

hanks largely to Sacagawea, the Shoshone gave Lewis and Clark advice about how to cross the mountains, and horses to carry their goods. The Corps continued west, making it all the way to the Pacific coast by November 1805. Here Clark wrote his famous line:

“Ocian in View! O! the joy.”

William Clark

That was Clark: good explorer, bad speller.

Lewis and Clark headed home the following year. They made it back without any major disasters, unless you count the time Lewis and the nearsighted Corps member Pierre Cruzatte went hunting for elk. Lewis spotted an animal and was aiming his gun when he felt a sudden and terrible pain in his butt. He turned around and saw blood running down his thigh.

“You have shot me,” he said to Cruzatte.

Cruzatte denied it, which was silly since the bullet from his gun was clearly lodged in Lewis's leather pants.

So for a few weeks Lewis had to ride in the canoe lying on his stomach. Still, the Corps made it safely back to St. Louis in September 1806. In two and a half years, Lewis and Clark had zigzagged more than eight thousand miles across the West, met with about fifty Indian groups, and found hundreds of species of plants and animals. Reports of their adventures got Americans excited about exploring the West.

O

ne of the things Lewis and Clark reported was that the rivers and streams of the West were filled with beaver. This caught people's attention, because hats made of beaver fur were currently in fashion in European cities (rich folks simply had to have their beaver hats). There was big money in the beaver pelt business. The only hard part: someone had to go get the pelts.

ne of the things Lewis and Clark reported was that the rivers and streams of the West were filled with beaver. This caught people's attention, because hats made of beaver fur were currently in fashion in European cities (rich folks simply had to have their beaver hats). There was big money in the beaver pelt business. The only hard part: someone had to go get the pelts.

James Beckwourth decided to give it a try. After being freed from slavery as a boy, Beckwourth had moved with his family to St. Louis. When he was twenty-four he heard that companies were looking for

daring young men to head west into the unmapped mountains to trap beaver. Beckwourth rushed to sign up.

daring young men to head west into the unmapped mountains to trap beaver. Beckwourth rushed to sign up.

James Beckwourth

“Being possessed with a strong desire to see the celebrated Rocky Mountains, and the great western wilderness so much talked about, I engaged in General Ashley's Rocky Mountain Fur Company.”

Beckwourth was one of a few hundred adventurers who became known as “mountain men.” Exploring the mountains and trapping beaver in icy streams, mountain men were often freezing, starving, and lonely. And they were always on the lookout for mountain lions and grizzly bears. Mountain man Jedediah Smith was searching for a route through the Rockies when he was attacked by a grizzly. The bear smacked Smith around like a doll, smashing several of his ribs. Then it took Smith's head in its teeth and shook him back and forth.

Fellow mountain man James Clyman found Smith lying in the bloody dirt. Smith somehow managed to say, “If you have a needle and thread, get it out and sew up my wounds around my head.”

Clyman crouched down to have a look. The scalp had been ripped from Smith's skull. One ear was hanging on by a twisted strip of skin.

“I told him I could do nothing for his ear,” Clyman said.

“Oh, you must try to stitch it up some way or other,” pleaded Smith.

Clyman took out the tools he used to mend his socks and went to work. “I put in my needle and stitched it through and through and over and over,” he said, “nice as I could.”

Incredibly, Smith's ear stayed on. And he was back on his horse in less than two weeks.

Other books

The Windermere Witness by Rebecca Tope

No Moon by Irene N.Watts

Flight by Alyssa Rose Ivy

Tom Jones Saves the World by Herrick, Steven

Dolly by Anita Brookner

Today Will Be Different by Maria Semple

It's Not Like I Knew Her by Pat Spears

Sovereign (Sovereign Series) by Arroyo, E.R.

For Nick by Dean, Taylor

The Complete Book of Raw Food by Julie Rodwell