Which Way to the Wild West? (6 page)

Read Which Way to the Wild West? Online

Authors: Steve Sheinkin

T

he snow starts falling early in the Sierra Nevada, so it was absolutely essential for travelers to get up and over these rugged mountains by October.

he snow starts falling early in the Sierra Nevada, so it was absolutely essential for travelers to get up and over these rugged mountains by October.

With this in mind, a businessman named John Hastings started selling a guide to the California Trail in 1845. In the book he described a shortcut that would allow travelers to reach the Sierra Nevada more quickly. The so-called Hastings Cutoff really was shorter. Unfortunately for travelers, Hastings failed to mention the massive deserts and canyons and mountains along his recommended routeâpossibly because he had never actually seen the route. He just wanted to make it sound easy to get to California so people would come there and buy stuff from his stores.

A year after Hastings's guide was published, a group of about eighty travelers led by the Donner and Reed families read the book. “Hastings's cutoff is said to be a savings of 350 or 400 miles, and a better route,” said James Reed.

He and his friends decided to give it a try.

“I was a child when we started to California,” said James Reed's daughter Virginia, who was twelve when the trip began. “Yet I remember the journey well and I have cause to remember it.”

The Donner Party, as they became known, left the established trail in August, heading into the deserts west of the Great Salt Lake. With only Hastings's inaccurate maps to guide them, the group was soon lost and dangerously low on water. They lightened their wagons by tossing belongings out onto the baking sand. Their oxen started dying anyway.

Growing increasingly tense and desperate, some of the men started fighting. A man named John Snyder attacked James Reed with a whip. Reed stabbed Snyder, killing him. Though Reed had acted in self-defense, the other men voted to kick Reed out of the group. He was sent off into the desert without food or weapons.

“When we learned of this decision, I followed him through the darkness ⦠and carried him his rifle, pistols, ammunition, and some food. I had determined to stay with him, and begged him to let me stay, but he would listen to no argument, saying that it was impossible.”

Virginia was crying so hard, she could barely walk back to camp. When she got there, she saw the fear in the eyes of her mother and younger sister and brothers. “It seemed suddenly to make a woman of me,” she said. “I realized that I must be strong.”

Virginia Reed

T

he Donner Party continued west, beginning their climb into the Sierra Nevada in late October. Snow flurries were already starting.

he Donner Party continued west, beginning their climb into the Sierra Nevada in late October. Snow flurries were already starting.

“The farther we went up, the deeper the snow got,” Virginia said. “The wagons could not go.”

By early November the whole group was stuck in snowdrifts high in the mountains. They built tiny wooden cabins, and killed and ate

the last of their animals. Every day the snow piled higher: ten feet, then twenty, then twenty-five. And months of winter still lay ahead.

the last of their animals. Every day the snow piled higher: ten feet, then twenty, then twenty-five. And months of winter still lay ahead.

Facing certain starvation, fifteen of the strongest members of the party (ten men and five women) decided to try to make it out of the mountains and send back help. They took enough food for six days.

Nine days later they were hopelessly lost in the snowy peaks. As the men and women huddled together around a tiny fire, someone brought up the awful question on everyone's mind: Should they kill and eat one member of the group in order to save the others? “Even the wind seemed to hold its breath as the suggestion was made that were one to die, the rest might live,” Virginia wrote. “Then the suggestion was made that lots be cast and whoever drew the longest slip should be the sacrifice.”

No one had the heart to go through with the plan. But when several group members died of cold and starvation over the next few nights, the others did the only thing they could to survive: they cut flesh from the bodies, roasted it, and ate it. Then they packed up the extra meat (carefully labeling the pieces, so no one would eat his or her own family member) and continued the journey. Seven of them (two of the men and all five of the women) made it out of the mountains alive, reaching settlements in California.

As news of the Donner Party spread, volunteer rescue crews rushed into the mountains to try to save the people still stuck there. A volunteer named Daniel Rhoads found the spot where the Donner Party cabins were supposed to be. He saw no sign of the buildings. Then he realized he was standing on themâthe cabins had been completely buried by snow.

“We saw a woman emerge from a hole in the snow,” Rhoads reported. “As we approached her, several others made their appearance, in like manner coming out of the snow.”

One of the women, barely more than a skeleton, said in a shaky voice: “Are you men from California or do you come from heaven?”

Other rescue teams soon arrived, including one led by Virginia Reed's father, James (who had found his way to California on his own). Of the eighty-six members of the Donner Party, forty-one died before the last survivors were rescued in April 1847. Amazingly, Virginia's entire family survived. More amazingly, Virginia seemed to quickly put the winter's horrors behind her. “We are all very well pleased with California,” she wrote to a cousin that spring. “It is a beautiful country. It ought to be a beautiful country to pay us for our trouble getting there.”

She added this advice for anyone thinking of coming to California: “Remember, never take no cutoffs and hurry along as fast as you can.”

P

resident James K. Polk wasn't thinking of going to California. He was thinking about how to make it part of the United States.

resident James K. Polk wasn't thinking of going to California. He was thinking about how to make it part of the United States.

Remember, Polk had run for president on the promise of expanding American territory. Last we heard, Polk was threatening to fight Great Britain over Oregon and Mexico over the rest of the West.

The Oregon conflict turned out to be pretty easy to resolve. After lots of tough talk, Britain and the United States agreed to simply split the territory. In June 1846 the United States officially took over the huge chunk of land that is now the northwest region of the country.

The conflict with Mexico was much more dangerous. Furious Mexican leaders had two major complaints. One, the United States had no right to annex Texas, they argued. Two, even if the United States did annex Texas, Americans were grabbing too much land. The Mexicans insisted that the Nueces River formed the southern border of Texas. Everything south of the river was not part of Texasâso it was still Mexican territory, annexation or no annexation.

Polk saw it differently. He argued that the border of Texas was actually 150 miles farther south, at the Rio Grandeâso all that extra land came with Texas.

With this border dispute raging, Polk offered to buy New Mexico and California from Mexico. It probably wasn't the right time to ask. In no mood to lose even more land to the Americans, offended Mexican leaders angrily rejected Polk's offer.

Then Polk cranked the tension up another notch. In March 1846 he sent American soldiers to Texas. Under Polk's orders, the troops crossed the Nueces River and continued south into the land claimed by both the United States and Mexico. The soldiers were there to defend American territory, Polk explained.

But to Mexican officials, this was an invasion of the Mexican state of Tamaulipas. General Pedro de Ampudia warned the Americans:

“If you insist on remaining upon the soil of the Department of

Tamaulipas, it will certainly result that arms, and arms alone, must decide the question.”

General Zachary Taylor, commander of the American troops, assured the Mexicans that he did insist on remaining. By April the two armies were glaring at each other across the one-hundred-yard-wide Rio Grande.

Both sides expected an explosion of violence at any moment.

Pedro de Ampudia

On April 25, 1846, Mexican soldiers splashed across the Rio Grande and attacked a small group of American troops. Sixteen Americans were killed, and the rest captured. “Hostilities have commenced,” General Taylor wrote to President Polk. When the letter reached Washington (it took a couple of weeks), Polk immediately went to Congress to demand a declaration of war: “Mexico has passed the boundary of the United States,” he said, “has invaded our territory and shed American blood upon the American soil.”

H

ad the shooting really started in American territory? Some members of Congress didn't think so. “That soil was not ours,” said a little-known House member from Illinois named Abraham Lincoln. To Lincoln, it looked like Polk had purposely sent Americans soldiers into the disputed territory in order to spark a war with Mexico. The war would give the United States an excuse to capture the land Mexico had refused to sell.

Pretty rotten,

thought Senator Alexander Stephens of Georgia: “The principle of waging war against a neighboring people to compel them to sell their country, is not only dishonorable, but disgraceful.”

ad the shooting really started in American territory? Some members of Congress didn't think so. “That soil was not ours,” said a little-known House member from Illinois named Abraham Lincoln. To Lincoln, it looked like Polk had purposely sent Americans soldiers into the disputed territory in order to spark a war with Mexico. The war would give the United States an excuse to capture the land Mexico had refused to sell.

Pretty rotten,

thought Senator Alexander Stephens of Georgia: “The principle of waging war against a neighboring people to compel them to sell their country, is not only dishonorable, but disgraceful.”

Polk objected, pointing out that Mexico had started the shooting. He had always wanted peace with Mexico, he insisted. His opponents joked that what Polk really wanted was not peace

with

Mexico, but a piece

of

Mexico.

with

Mexico, but a piece

of

Mexico.

Either way, the public was on Polk's side. American soldiers had been attacked, and there was strong support for war. Congress voted to declare war on Mexico in May 1846. Thousands of Americans rushed to volunteer for military service.

As for Abraham Lincoln, he soon heard from angry voters back home, who said his opposition to the war was pretty much an act of treason. One Illinois newspaper actually called him “a second Benedict Arnold.” That was the end of Lincoln's political career, experts said.

“M

exico should fight to the end,” declared a newspaper in the Mexican city of Nuevo Leon. “As long as there is one man remaining, he should go and fight the unjust invaders.”

exico should fight to the end,” declared a newspaper in the Mexican city of Nuevo Leon. “As long as there is one man remaining, he should go and fight the unjust invaders.”

The problem with this plan: the Mexican army was in awful shape. Most Mexican soldiers had very little training and terrible equipment, including old-fashioned muskets sold to them by the British (left over from wars Britain had fought thirty years ago). The army could not even have survived without

soldaderas,

women who traveled along with the troops and did work the army should have done: cooking, making uniforms, caring for the sick and wounded.

soldaderas,

women who traveled along with the troops and did work the army should have done: cooking, making uniforms, caring for the sick and wounded.

Another serious problem was that the Mexican army was led by General Antonio López de Santa Anna, the self-proclaimed genius who had lost Texas. Santa Anna was good at talking tough, not so good at actual fighting. When his army faced Americans at the Battle of Buena Vista in early 1847, Santa Anna demanded that the Americans surrender in order to save themselves.

“Tell Santa Anna to go to [censored]!” barked Zachary Taylor. Then Taylor turned to a staff member and said: “Major Bliss, put that in Spanish, and send it back.”

Bliss put Taylor's main idea into slightly more polite language: “I beg leave to say that I decline acceding to your request.”

Santa Anna attacked, lost five times more men than the Americans, and declared victory. Then he retreated. In a series of short, brutal battles in the spring and summer of 1847, the American army continued slashing its way toward Mexico City.

Meanwhile, the war with Mexico gave Polk an excuse to do something he'd wanted to do anywayâsend American troops to capture California.

M

ariano Guadalupe Vallejo woke suddenly on the morning of June 14, 1846, startled by the sounds of shouts and horses. “I looked out of my bedroom window,” Vallejo said. “To my great surprise, I made out groups of armed men scattered to the right and left of my residence.”

ariano Guadalupe Vallejo woke suddenly on the morning of June 14, 1846, startled by the sounds of shouts and horses. “I looked out of my bedroom window,” Vallejo said. “To my great surprise, I made out groups of armed men scattered to the right and left of my residence.”

As Mexico's military commander in northern California (and uncle to the young pioneer Guadelupe Vallejo), Vallejo had always been welcoming to American immigrants. He often invited newcomers to stay at his large ranch in Sonoma and helped them settle in California. But that did him no good when armed Americans banged on his door.

“My wife advised me to try and flee by the rear door,” Vallejo remembered. “But I told her that such a step was unworthy and that under no circumstances could I decide to desert my young family at such a critical time.” He jumped into his general's uniform and opened his door. “The house was immediately filled with armed men,” he said.

These weren't Polk's soldiersâjust regular guys with guns, wearing greasy clothes and very dirty hats. “They were about as roughlooking a set of men as one could well imagine,” admitted Robert Semple, one of the Americans.

Too polite to say what he was really thinking, Vallejo asked, “To what happy circumstances shall I attribute the visit of so many exalted personages?”

Shouting all at once, the Americans declared that they were there to arrest Vallejo. They were seizing California from Mexico! (And while they were at it, they seized Vallejo's brandy, and downed it in quick gulps.)

Then the Americans marched to the town plaza in Sonoma, declared California to be an independent republic, and raised a homemade flag on which they had painted a grizzly bear. Well, it was supposed to be a bear.

“The bear was so badly painted,” Vallejo said, “it looked more like a pig than a bear.”

Anyway, the key point is that these Americans had heard that the United States was at war with Mexico. They decided it was a good time to seize California for their country.

A few weeks later, the American soldiers and sailors sent by President Polk started arriving. They took control of California for the United States.

I

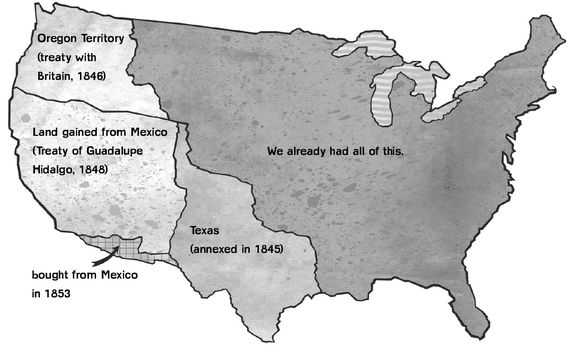

n September 1847 American soldiers captured Mexico City. Having lost the war, Mexican leaders were forced to accept the same basic deal they had angrily rejected two years before. In the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Mexico gave up nearly half its territory, including the disputed land in Texas, all of California, New Mexico, and the rest of what is now the southwestern United States. The United States paid Mexico fifteen million dollars.

n September 1847 American soldiers captured Mexico City. Having lost the war, Mexican leaders were forced to accept the same basic deal they had angrily rejected two years before. In the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Mexico gave up nearly half its territory, including the disputed land in Texas, all of California, New Mexico, and the rest of what is now the southwestern United States. The United States paid Mexico fifteen million dollars.

Now the West is West: U.S. in 1848

Now all the land we think of as the West today was part of the United States.

W

hile all this was going on, more and more Americans were showing up in the West. Followers of the new Mormon religion even established their own western trail. After getting violently chased out of towns in Missouri and Illinois, the Mormons were looking for a new place to settle. The Mormon leader Brigham Young read about the Great Salt Lake Valleyâa giant salty lake surrounded by deserts. It sounded like a good place to be left alone.

hile all this was going on, more and more Americans were showing up in the West. Followers of the new Mormon religion even established their own western trail. After getting violently chased out of towns in Missouri and Illinois, the Mormons were looking for a new place to settle. The Mormon leader Brigham Young read about the Great Salt Lake Valleyâa giant salty lake surrounded by deserts. It sounded like a good place to be left alone.

In the spring of 1847, Young and his followers established the Mormon Trail, a 1,300-mile route from Illinois to what is now Utah. When the travelers arrived in the Salt Lake Valley, they were not impressed. “A paradise of the lizard, the cricket, and the rattlesnake,” one settler said. That was fine by Brigham Young.

“I want hard times, so that every person that does not wish to stay for the sake of his religion will leave.”

Brigham Young

The Mormon settlers began irrigating fields, planting crops, building homes, and laying out the streets of a new town. It took them just a few years to turn Salt Lake City into the second-largest city west of Missouri (only San Francisco was bigger).

M

eanwhile, thousands of other Americans were heading west, most of them on the Oregon Trail. When they arrived in Oregon, many travelers stopped to rest at the home of Narcissa and Marcus Whitmanâremember them? They're the missionaries who had settled in Oregon and taken in the orphaned Sager children.

eanwhile, thousands of other Americans were heading west, most of them on the Oregon Trail. When they arrived in Oregon, many travelers stopped to rest at the home of Narcissa and Marcus Whitmanâremember them? They're the missionaries who had settled in Oregon and taken in the orphaned Sager children.

The Cayuse and other Indians of the region watched this migration with growing alarm. Ten years before, Cayuse leaders had invited the Whitmans to settle on their land. The Whitmans told them they were there to teach and help the local people. But now the Whitmans were using their house as a welcome station for huge groups of white settlers. This was not at all what the Cayuse had agreed to. “The poor Indians are amazed at the overwhelming numbers of Americans coming into the country,” Narcissa Whitman wrote.

They had good reason to be amazed, and angry too. The new settlers not only grabbed big chunks of land, but they also brought diseases that had not existed in that part of the world. Measles, for example, was not very dangerous for people of European background. They had developed natural defenses to it over many centuries. But when American settlers brought measles to Oregon in 1847, the disease quickly killed half the people in many Cayuse villagesâand nearly all of the children.

Unable to escape from this nightmare, some Cayuse began

wondering,

How come Marcus Whitman, who is a doctor, is able to cure most of the white children, while our own children continue to die?

A rumor started spreading that the Whitmans were purposely using the disease to wipe the Cayuse out.

wondering,

How come Marcus Whitman, who is a doctor, is able to cure most of the white children, while our own children continue to die?

A rumor started spreading that the Whitmans were purposely using the disease to wipe the Cayuse out.

“The disease was raging fearfully among the Indians, who were rapidly dying,” said Catherine Sager. “I saw from five to six buried daily.” Four years earlier Catherine had watched her parents die on the Oregon Trail. Now she was thirteen and in for another horrible shock.

Other books

Never Let You Down: The Connaghers, Book 4 by Joely Sue Burkhart

If I Stay by Reeves, Evan

Chiara – Revenge and Triumph by Gian Bordin

The Last Van Gogh by Alyson Richman

Wilde for Her (A Wilde Security Novel) (Entangled Brazen) by Burrows, Tonya

Always Yesterday by Jeri Odell

His to Command #1: The Chase by Carew, Opal

Red Sky at Night (Home in the stars, #0.5) by Jolie Mason