Why the West Rules--For Now (43 page)

Read Why the West Rules--For Now Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Tags: #History, #Modern, #General, #Business & Economics, #International, #Economics

Zhuangzi thought that Liezi made Confucius’ and Mozi’s activism look ridiculous—and dangerous. “You can’t bear the sufferings of this one generation,” Zhuangzi imagined someone saying to Confucius, “therefore you go and cause trouble for ten thousand generations to come. Do you set out to be this miserable, or don’t you realize what you are doing? … What is wrong cannot but harm and what is active cannot fail to be wrong.” Mozi, by contrast, struck Zhuangzi as “one of the good of this world,” but someone who took the fun out of life. “Mohists wear skins and coarse cloth, wooden shoes or hemp sandals, never stop night and day, and view such fervent activity as their highest achievement.” Yet this only produced “A life that is laborious and a

death that is insignificant … Even if Mozi himself could stand it,” Zhuangzi asked, “how can the rest of the world be expected to live this way?”

Mozi rejected Confucius; Zhuangzi rejected Confucius

and

Mozi; but the so-called Legalist Tradition rejected them all. Legalism was the anti-Axial option, more Machiavellian than Machiavelli.

Ren

,

jian ai

, and

dao

, Legalists felt, all missed the point. Trying to transcend reality was stupid: godlike kings had yielded to managerial, efficiency-seeking ones, and the rest of us should get with the program. For Lord Shang, a fourth-century-

BCE

chief minister of Qin and Legalism’s guiding light, the goal was not humaneness; it was “

the enrichment

of the state and the strengthening of its military capacity.” Do not do unto others as you would have them do unto you, said Lord Shang, because “If in enterprises you undertake what the enemy would be ashamed to do, you have the advantage.” Neither be good nor do good, because “A state that uses the wicked to govern the good always enjoys order and becomes strong.” And waste no time on rituals, activism, or fatalism. Instead draw up comprehensive law codes with brutal penalties (beheading, burial alive, hard labor) and impose them rigidly on everyone. Like a carpenter’s square, Legalists liked to say, laws force messy materials to conform.

Chinese Axial thought ranged from mysticism to authoritarianism, and was constantly evolving. The third-century-

BCE

scholar Xunzi, for instance, combined Confucianism with Mozi’s ideas and Daoism and sought middle ground with Legalism. Plenty of Legalists welcomed Mozi’s work ethic and the Daoists’ acceptance of things. Over the centuries ideas were combined and recombined in kaleidoscopic complexity.

Much the same was true of Axial thought in South Asia and the West. I will not work through these traditions in detail, but even a quick look at the small land of Greece gives a sense of the bubbling cauldron of ideas. Godlike kingship may have been weaker in Greece before 1200

BCE

than in the older states of southwest Asia, and by 700 Greeks had rejected it decisively. That, perhaps, was why they went on to confront even more starkly than others in the Axial Age the question of what a good society should look like in the absence of rulers who tapped into another world.

One Greek response was to seek the good through collective politics. If no one had access to supernatural wisdom, some Greeks asked, why not pool the limited knowledge each man does have to create a (male) democracy? This was a distinctive idea—not even Mozi had thought of it—and long-term lock-in theorists often suggest that the Greek invention of male democracy marks a decisive rupture between the West and the rest.

By this point in the book it will probably be no surprise to hear that I am not convinced. Western social development had been higher than Eastern for fourteen thousand years before Greeks started voting on things, and the West’s lead barely changed during the fifth and fourth centuries

BCE

, the golden age of Greek democracy. Only in the first century

BCE

, when the Roman Empire had made democracy redundant, did the West’s lead over the East rise sharply. An even greater problem with the Greek-rupture theory (as will become clear in

Chapters 6

through

9

) is that democracy disappeared from the West almost completely in the two thousand years separating classical Greece from the American and French revolutions. Nineteenth-century radicals certainly found ancient Athens a useful foil in their debates over how modern democracies might work, but it takes a heroically selective reading of history to see a continuous spirit of democratic freedom stretching from classical Greece to the Founding Fathers (who, incidentally, tended to use the word “democracy” as a term of abuse, just one step above mob rule).

In any case, Greece’s real contribution to Axial thought came not from democrats but from the critics of democracy, led by Socrates. Greece, he argued, did not need democracies, which merely pooled the ignorance of men who judged everything by appearances; what it needed was men like himself, who knew that when it came to the one thing that mattered—the nature of the good—they knew nothing. Only such men could hope to understand the good (if, indeed, anyone could; Socrates was not sure) through reason, honed in philosophical debate.

Plato, one of Socrates’ followers, produced two versions of the master’s model for the good society:

The Republic

, idealistic enough for any Confucian, and

The Laws

, authoritarian enough to warm Lord Shang’s heart. Aristotle (one of Plato’s pupils) covered a similar range, from the humane

Ethics

to the coldly analytical

Politics.

Some of the

fifth-century-

BCE

thinkers known as Sophists could match Daoists for relativism, just as the visionaries Parmenides and Empedocles matched them for mysticism; and Protagoras was as much a champion of the common man as Mozi.

In the introduction to this book I talked about another long-term lock-in theory, which holds that the West rules today not because ancient Greeks invented democracy per se but because they created a uniquely rational, dynamic culture while ancient China was obscurantist and conservative.

*

I think this theory is wrong too. It caricatures Eastern, Western, and South Asian thought and ignores their internal variety. Eastern thought can be just as rational, liberal, realist, and cynical as Western; Western thought can be just as mystical, authoritarian, relativist, and obscure as Eastern. The real unity of Axial thought is unity in diversity. For all the differences among Eastern, Western, and South Asian thought, the

range

of ideas, arguments, and conflicts was remarkably similar in each region. In the Axial Age, thinkers staked out the same terrain for debate regardless of whether they lived in the Yellow River valley, the Ganges plain, or the cities of the eastern Mediterranean.

The real break with the past was the shape of this intellectual terrain

as a whole

, not any single feature (such as Greek philosophy) within it. No one was having Axial arguments in 1300

BCE

, when the West’s social development score first approached twenty-four points. The closest candidate is Akhenaten, pharaoh of Egypt between 1364 and 1347

BCE

, who swept aside traditional gods and installed a trinity of himself, his wife, Nefertiti, and the sun disk, Aten. He built a new city full of temples to Aten, composed haunting hymns, and promoted a deeply strange art style.

For a hundred years Egyptologists have argued over what Akhenaten was doing. Some think he was trying to invent monotheism; no less a luminary than Sigmund Freud argued that Moses stole this concept from Akhenaten while the Hebrews were in Egypt. There are certainly striking parallels between Akhenaten’s “Great Hymn to the Aten” and the Hebrew Bible’s Psalm 104, the “Hymn to God the Creator.”

Yet Akhenaten’s religious revolution was anything but Axial. It had no room for personal transcendence; in fact, Akhenaten banned mere mortals from worshipping Aten at all, making the pharaoh even more of a bridge between this world and the divine than he had been before.

If anything, Atenism illustrates the difficulty of making major intellectual changes in societies where god-kings are firmly ensconced. His new religion won no following, and as soon as he died the old gods were brought back. Akhenaten’s temples were smashed and his revolution forgotten until archaeologists dug his city up in 1891.

So is Axial thought the secret ingredient that makes

Figure 5.1

so dull? Did Confucius, Socrates, and the Buddha guide societies through some intellectual barrier when social development reached twenty-four points in the mid first millennium

BCE

, while the absence of such geniuses blocked social development in the second millennium?

Probably not. For one thing, chronology is against it. In the West, Assyria became a high-end state and pushed past twenty-four points in the eighth century

BCE

, but it is hard to see much that is strikingly Axial in Western thought before Socrates, three hundred years later. It is a closer call in the East; there Qin, Chu, Qi, and Jin reached twenty-four points around 500

BCE

, just when Confucius was most active, but the main wave of Eastern Axial thought falls later, in the fourth and third centuries

BCE

. And if South Asianists are right in redating the Buddha to the late fifth century

BCE

, high-end state formation seems to precede Axial thought there, too.

Geography is also against it. The most important Axial thinkers came from small, marginal communities such as Greece, Israel, the Buddha’s home state of Sakya, or Confucius’ of Lu; it is hard to see how transcendent breakthroughs in political backwaters affected social development in the great powers.

Finally, logic is against it. Axial thought was a reaction against the high-end state, at best indifferent to great kings and their bureaucrats and often downright hostile to their power. Axial thought’s real contribution to raising social development, I suspect, came later in the first millennium

BCE

, when all the great states learned to tame it, making it work for them. In the East, the Han dynasty emasculated Confucianism to the point it became an official ideology, guiding a loyal class of

bureaucrats. In India, the great king Ashoka, apparently genuinely horrified by his own violent conquests, converted to Buddhism around 257

BCE

, yet somehow managed not to renounce war. And in the West the Romans first neutralized Greek philosophy, then turned Christianity into a prop for their empire.

The more rational strands within Axial thought encouraged law, mathematics, science, history, logic, and rhetoric, which all increased people’s intellectual mastery of their world, but the real motor behind

Figure 5.1

was the same as it had been since the end of the Ice Age. Lazy, greedy, and frightened people found easier, more profitable, and safer ways to do things, in the process building stronger states, trading farther afield, and settling in greater cities. In a pattern we will see repeated many times in the next five chapters, as social development rose the new age got the culture it needed. Axial thought was just one of the things that happened when people created high-end states and disenchanted the world.

EDGE EMPIRES

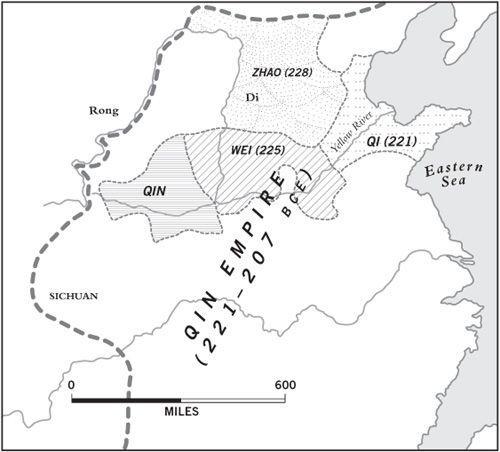

If further proof is needed that Axial thought was more a consequence than a cause of state restructuring, we need only look at Qin, the ferocious state at the western edge of the Eastern core (

Figure 5.6

). “

Qin has the same

customs as the [barbarians] Rong and Di,” said the anonymous author of

The Stratagems of the Warring States

, a kind of how-to book on diplomatic chicanery. “It has the heart of a tiger or wolf; greedy, loving profit, and untrustworthy, knowing nothing of ritual, duty, or virtuous conduct.” Yet despite being the antithesis of everything Confucian gentlemen held dear, Qin exploded from the edge of the Eastern core to conquer the whole of it in the third century

BCE

.

Something rather similar also happened at the other end of Eurasia, where the Romans—also regularly likened to wolves—came from the edge of the Western core to overthrow it and enslave the philosophers who called them barbarians. Polybius, a Greek gentleman taken to Rome as a hostage in 167

BCE

, wrote a forty-volume

Universal History

to explain all this to his fellow countrymen. “Who,” he asked, “

can be

so narrow-minded or lazy that he does not want to know how … in

less than fifty-three years [220–167

BCE

] the Romans brought under their rule almost the whole inhabited world,

*

something without parallel in history?”

Figure 5.6. The triumph of Qin: the East in the era of Warring States, 300–221

BCE

(dates in parentheses show when the main states fell to Qin)