Why the West Rules--For Now (67 page)

Read Why the West Rules--For Now Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Tags: #History, #Modern, #General, #Business & Economics, #International, #Economics

Right up to the last moment it was touch-and-go what the pestilence would do first—leave Zheng’s barbarians too weak to storm Tenochtitlán or the enemy barbarians too weak to defend it. But once again Heaven decided in Zheng’s favor, and under cover of the last bombs and crossbow bolts his horsemen had led the charge across the causeways into Tenochtitlán. After a vicious but one-sided struggle in the streets—Aztec stone blades and cotton padding against Chinese steel swords and chain mail—resistance collapsed and the Purépecha set about torturing, raping, and stealing. Itzcoatl, the last Aztec king, they pierced with many darts as he fought at the gate of his palace, then threw him into a fire, carved out his heart before he died, and—horror of horrors—sliced off and ate chunks of his flesh.

Zheng’s questions had been answered. These people were not immortals. Nor was he King Wu, initiating a new age of virtue. The only question remaining, in fact, was how he would get all his plunder back to Nanjing.

GREAT MEN AND BUNGLING IDIOTS

In reality, of course, things didn’t happen this way, any more than things in 1848 happened the way I described in the introduction. Tenochtitlán did get sacked, its Mesoamerican neighbors did do most of the fighting, and imported diseases did kill most people in the New World. But the sack came in 1521, not 1431; the man who led it was Hernán Cortés, not Zheng He; and the killer germs came from Europe, not Asia. If Zhou Man really had discovered the Americas, as Menzies insists, and if the story really had unfolded the way I just told it, with Mexico becoming part of the Ming Empire, not the Spanish, the modern world might look very different. The Americas might have been tied into a Pacific, not an Atlantic economy; their resources might have fueled an Eastern, not a Western industrial revolution; Albert might have ended up in Beijing rather than Looty in Balmoral; and the West might not rule.

So why did things happen the way they did?

Ming dynasty ships certainly could have sailed to America if their skippers had wanted to. A replica of a Zheng-era junk in fact managed the China–California trip in 1955 (though it could not get back again) and another, the

Princess Taiping

, got within twenty miles of completing a Taiwan–San Francisco round trip in 2009 before a freighter sliced it in two.

*

If they could do it, why didn’t Zheng?

The most popular answer is that things happened the way they did because in the fifteenth century Chinese emperors lost interest in sending ships overseas, while European kings (some, anyway) became very interested in it. And up to a point, that is clearly correct. When Yongle died in 1424 his successor’s first act was to ban long-distance voyages. Predictably, the princes of the Indian Ocean stopped sending tribute, so the next emperor sent Zheng back to the Persian Gulf in 1431, only for his successor, Zhengtong, to reverse policy again. In 1436 the court refused repeated requests from the shipyards at Nanjing for more craftsmen, and over the next decade or two the great fleet rotted. By

1500 no emperor could have repeated Yongle’s voyages even if he had wanted to.

At the other end of Eurasia, royalty was behaving in exactly the opposite way. Portugal’s Prince Henry “the Navigator” poured resources into exploration. Some of his motives were calculating (such as lust for African gold) and some otherworldly (such as the belief that somewhere in Africa there was an immortal Christian king named Prester John, who guarded the Gates of Paradise and would save Europe from Islam). All the same, Henry funded expeditions, hired map-makers, and helped design new ships that were perfect for exploring the west coast of Africa.

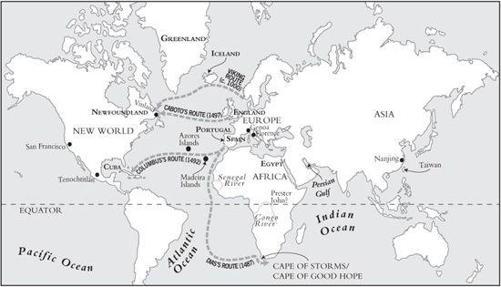

Portuguese exploration was certainly not all smooth sailing. Upon discovering the uninhabited Madeira Islands (

Figure 8.8

) in 1420, the captain in charge (Christopher Columbus’s future father-in-law) released a mother rabbit and her young on Porto Santo, the most promising piece of real estate. Breeding like they do, the bunnies ate everything, forcing the humans to relocate to the densely forested main island of Madeira (“wood” in Portuguese). This island the colonists set alight, compelling them, a chronicler tells us, “

with all the men

, women, and children, to flee [the fire’s] fury and to take refuge in the sea, where they remained up to their necks in the water, and without food or drink for two days and two nights.”

But having destroyed the native ecosystem, the Europeans discovered that sugarcane thrived in this charred new world, and Prince Henry put up the money for them to build a mill. Within a generation they were importing African slaves to labor in their plantations, and by the fifteenth century’s end the settlers were exporting more than six hundred tons of sugar every year.

Plunging farther into the Atlantic, Portuguese sailors found the Azores, and nudging down the African coast, they reached the Senegal River in 1444. In 1473 their first ship crossed the equator, and in 1482 they reached the Congo River. Here, for a while, headwinds made sailing farther south impossible, but in 1487 Bartolomeu Dias hit on the idea of

volta do mar

, “returning by sea.” Swinging far out into the Atlantic, he picked up winds that carried him to what he named the Cape of Storms (known today, more optimistically, as the Cape of Good Hope) at Africa’s southern tip, where his terrified sailors mutinied and

forced him home. Dias had not found Prester John, but he had shown there could be a sea route to the Orient.

Figure 8.8. The world as seen from Europe, and the paths taken by fifteenth-century European explorers

By Yongle’s standards the Portuguese expeditions were laughably small (involving dozens of men, not dozens of thousands) and undignified (involving rabbits, sugar, and slaves, not gifts from great princes), but with the benefit of hindsight it is tempting to see the 1430s as a—perhaps the—decisive moment in world history, the point when Western rule became possible. At just the moment that maritime technology began to turn the oceans into highways linking the whole planet, Prince Henry grasped the possibilities and Emperor Zhengtong rejected them. Here, if anywhere, the great man/bungling idiot theory of history seems to accomplish a lot: the planet’s fate hung on the decisions these two men made.

Or did it? Henry’s foresight was impressive, but certainly not unique. Other European monarchs were close on his heels, and in fact the private enterprise of countless Italian sailors drove the process quite as much as the whims of rulers. If Henry had taken up coin collecting instead of navigating, other rulers would have filled his shoes. When Portugal’s king John turned down the Genoese adventurer Christopher Columbus’s crazy-sounding scheme to reach India by sailing west, Queen Isabella of Castile stepped in (even if he had to pitch the idea to her three times to get to yes). Within a year Columbus was back, announcing—doubly confused—that he had reached the land of the great khan (his first mistake was that it was actually Cuba; his second, that the Mongol khans had been expelled from China over a century earlier). Panicked by reports of the Castilians’ new route to Asia, Henry VII of England sent the Florentine merchant Giovanni Caboto

*

to find a North Atlantic alternative in 1497. Caboto reached icy Newfoundland, and—as enthusiastically muddled as Columbus—insisted that this, too, was the great khan’s land.

By the same token, breathtaking as Zhengtong’s error now seems, we should bear in mind that when he “decided” not to send shipwrights to Nanjing in 1436 he was only nine years old. His advisers made this choice for him, and their successors repeated it throughout the fifteenth century. According to one story, when courtiers revived the idea of Treasure Fleets in 1477 a cabal of civil servants destroyed

the records of Zheng’s voyages. The ringleader, Liu Daxia, we are told, explained to the minister of war,

The voyages

of [Zheng] to the Western Ocean wasted millions in money and grain, and moreover the people who met their deaths may be counted in the tens of thousands … This was merely an action of bad government of which ministers should severely disapprove. Even if the old archives were still preserved they should be destroyed.

Grasping the point—that Liu had deliberately “lost” the documents—the minister rose from his chair. “Your hidden virtue, sir,” he exclaimed, “is not small. Surely this seat will soon be yours!”

If Henry and Zhengtong had been different people, making different decisions, history would still have turned out much the same. Maybe instead of asking why particular princes and emperors made one choice rather than another, we should ask why western Europeans embraced risk-taking just as an inward-turned conservatism descended on China. Maybe it was culture, not great men or bungling idiots, that sent Cortés rather than Zheng to Tenochtitlán.

BORN AGAIN

“

At the present

moment I could almost wish to be young again,” the Dutch scholar Erasmus wrote to a friend in 1517,

*

“for no other reason but this—that I anticipate the near approach of a golden age.” Today we know this “golden age” by the name Frenchmen gave it,

la renaissance

, “the rebirth”: and as some people see it, this rebirth was precisely the cultural force that suddenly, irreversibly, set Europeans apart from the rest of the world, making men like Columbus and Caboto do what they did. The creative genius of a largely Italian cultural elite—“

first-born

among the sons of modern Europe,” a nineteenth-century historian famously called them—set Cortés on the path to Tenochtitlán.

Historians normally trace the roots of the rebirth back to the twelfth century, when northern Italy’s cities shook off German and papal domination and emerged as economic powerhouses. Rejecting their recent

history of subjection to foreign rulers, their leaders began wondering how to govern themselves as independent republics, and increasingly concluded that they could find answers in classical Roman literature. By the fourteenth century, when climate change, famine, and disease undermined so many old certainties, some intellectuals expanded their interpretation of the ancient classics into a general vision of social rebirth.

Antiquity, these scholars started claiming, was a foreign country. Ancient Rome had been a land of extraordinary wisdom and virtue, but barbarous “Middle Ages” had intervened between then and modern times, corrupting everything. The only way forward for Italy’s newly freed city-states, intellectuals suggested, was by looking backward: they must build a bridge to the past so that the wisdom of the ancients could be born again and humanity perfected.

Scholarship and art would be the bridge. By scouring monasteries for lost manuscripts and learning Latin as thoroughly as the Romans themselves, scholars could think as the Romans had thought and speak as they had spoken; whereupon true humanists (as the born-again called themselves) would recapture the wisdom of the ancients. Similarly, by poking around Roman ruins, architects could learn to re-create the physical world of antiquity, building churches and palaces that would shape lives of the highest virtue. Painters and musicians, who had no Roman relics to study, made their best guesses about ancient models, and rulers, eager to be seen to be perfecting the world, hired humanists as advisers, commissioned artists to immortalize them, and collected Roman antiquities.

The odd thing about the Renaissance was that this apparently reactionary struggle to re-create antiquity in fact produced a wildly untraditional culture of invention and open-ended inquiry. There certainly were conservative voices, banishing some of the more radical thinkers (such as Machiavelli) to drain the bitter cup of exile and intimidating others (such as Galileo) into silence, but they barely blunted the thrust of new ideas.

The payoff was phenomenal. By linking every branch of scholarship, art, and crafts to every other and evaluating them all in the light of antiquity, “Renaissance men”

*

such as Michelangelo revolutionized

them all at once. Some of these amazing characters, such as Leon Battista Alberti, theorized as brilliantly as they created, and the greatest, such as Leonardo da Vinci, excelled at everything from portraiture to mathematics. Their creative minds moved effortlessly between studios and the corridors of power, taking time off from theorizing to lead armies, hold office, and advise rulers. (In addition to writing

The Prince

, Machiavelli also penned the finest comedies of his age.) Visitors and emigrants spread the new ideas from the Renaissance’s epicenter at Florence as far as Portugal, Poland, and England, where distinct local renaissances blossomed.

This was, without a doubt, one of the most astonishing episodes in history. Renaissance Italians did not re-create Rome—even in 1500, Western social development was still a full ten points lower than the Roman peak a millennium and a half earlier. More Italians could now read than in the heyday of the Roman Empire, but Europe’s biggest city was just one-tenth the size of ancient Rome; Europe’s soldiers, despite being armed with guns, would have struggled to better Caesar’s legions; and Europe’s richest countries remained less productive than Rome’s richest provinces. But none of these quantitative differences necessarily matters if Renaissance Italians really did revolutionize Western culture so thoroughly that they set Europe apart from the rest of the world, inspiring Western adventurers to conquer the Americas while conservative Easterners stayed home.