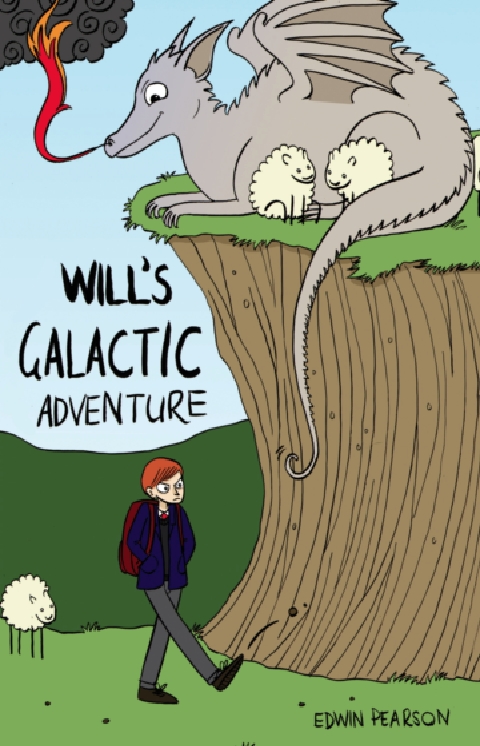

Will's Galactic Adventure

Read Will's Galactic Adventure Online

Authors: Edwin Pearson

EDWIN PEARSON

Copyright © 2013 Edwin Pearson

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study,

or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents

Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in

any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the

publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with

the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries

concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers.

Matador®

9 Priory Business Park

Kibworth Beauchamp

Leicestershire LE8 0RX, UK

Tel: (+44) 116 279 2299

Fax: (+44) 116 279 2277

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.troubador.co.uk/matador

ISBN 978 1783067 909

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Matador®

is an imprint of Troubador Publishing Ltd

Converted to eBook by

EasyEPUB

For Will, who inspired it, and for Lizzie and Hazel, who encouraged it.

“Come on Will â hurry up!”

“Stupid Mr Frobisher,” Will muttered under his breath. “He's the slowest driver in the universe but then brings us all out into the freezing cold and wants to hurry up. Should be hurrying back to a warm place, not squelching about in all this mud.”

Then out loud, “I'm coming sir.”

Mr Frobisher had brought a âlucky' few of those he thought of as his brightest pupils for a special end of term treat â a geography field trip to Wales.

Punishment, more like,

Will had thought.

Mr Frobisher was a very careful driver. In fact, he prided himself in being very careful at everything. He had driven the school minibus all the way to Wales at ten miles per hour slower than the speed limit, just to be on the safe side. Caravans had overtaken him. Once even a tractor pulling a muck spreader. He had also avoided motorways so as to give his victims â sorry, brightest pupils â a better opportunity to get a feel for the landscape. The landscape seemed to do an awful lot of going up and down and round and round, especially the closer they got to their final destination. Wherever that was. The result was that they had been on the road for hours.

To make matters worse, the batteries in Will's phone had packed up about three hours into the trip, so instead of playing the games he had been forced to listen to the monologue being delivered by the boy next to him, Osbert, who knew all there was to know about breeds of sheep. In Wales, as Will was now all too painfully aware, there are a lot of sheep.

He was hungry too. They had stopped once on the way for lunch but that was ages ago. They weren't on the motorway so they couldn't stop at the services and have a proper meal with burgers and stuff, so Mr Frobisher had chosen âa nice little tea shop' where two grumpy old ladies had grudgingly served them beans on toast and been pleased to see the back of them.

At last they arrived at their home for the next week. Home turned out to be what looked to Will like a cowshed: a long, low stone building with a slate roof and hardly any windows. In the swirling mist the grey stone looked almost black. Mr Frobisher had made a little teacher's joke that this was how you knew it was August â because in the other months it would be rain not mist. Unless it was snowing, of course.

“Ho ho,” they all chorused in reply, and squelched inside.

All except Osbert, that is. He really did think it was funny and skipped through the door, backpack over one shoulder. Now that really was funny. Not because he skipped through the door but because the damp grey slate roof was not the only damp grey slate around the place and Osbert slipped across the floor and landed heavily on his bum. Fortunately, this was more than adequate to cushion the impact.

Miles from anywhere as they were, Mr Frobisher still carefully locked the doors of the minibus and checked them all once again to be sure before following his pupils inside.

No sooner had they all found the creaky bunk beds, dumped their stuff and gone in search of the telly and the fridge (neither of which, it turned out, could be found) than a strange change began to come over Mr Frobisher. No longer was he the careful geography teacher. His eyes held the faraway stare of the pioneer who was always looking over the next range of hills to the one beyond. Not that he could even see the first range, what with the mist outside and his glasses being all steamed up with the dampness of the air in the â well, in the cowshed or whatever it was.

“Plenty of daylight left yet. Let's get some fresh air before bed time. Come on, get your boots and waterproofs on.”

So saying, Mr Frobisher began to don his own outdoor gear. Not for him the lightweight fabrics of modern high-tech mountain equipment. His kit had been bought when boots were boots and anoraks were anoraks. If it was good enough for Sir Edmund Hillary (Everest, 1953) it was good enough for him. One of the boys had once suggested that it was also probably good enough for Captain Scott (South Pole, 1912) but Mr Frobisher had rather missed the point.

Alpenstock (what?) in hand, knapsack on back, hob nails striking sparks from the rocks, Mr Frobisher strode off into the gloom of a Welsh mountain evening in August. Osbert was close behind, still limping slightly. He wanted Mr Frobisher to describe to him how the alpenstock (long wooden stick with metal pointy bits on the end, used by people up mountains to try and help them stop falling off the icy bits) had evolved into the modern ice axe (short wooden stick with different metal pointy bits on the end, used by people up mountains to try and help them stop falling off the icy bits). He got the first half of the story â at some length â but Mr Frobisher had little time for the ice axe. “Flimsy thing. Not long enough.”

The others trailed in their wake.

At the very end of the wake was Will.

“Come on Will â hurry up!”

Will wasn't really sure why he was here. He didn't think that he was a particular favourite of Mr Frobisher and he certainly wasn't a great enthusiast for geography. Or history for that matter. In fact, to Will's mind, it wasn't always easy to tell history and geography apart. He had been on field trips from school before and it didn't seem to matter whether they were for history or geography, either way he still ended up looking at piles of stones. The only real difference seemed to be that in history someone had piled up the stones whereas in geography the piles of stones had got there by themselves. This trip was only different from the others in that he couldn't see any piles of stones because the mist was so thick. He kept tripping over them, though, so he thought that this outing would probably turn out to be the same as all the others. Only longer. The others had been day-trips. This was for a whole week.

Will was just beginning to amuse himself by wondering how many interesting piles of stones he would not be able to see in this mist for a week, when he was snapped back to reality by a voice from somewhere up ahead.

“Getting quite thick now, this mist. Gets like this in summer sometimes. All to do with warm damp air rising to meet cooler dry air. I'll draw you a diagram when we get back. More fun to actually experience it than read about it though. Brings the subject to life, I always think.

“Still, don't want to get separated do we? An old pioneering trick in situations like this is to sing. Keeps the spirits up and lets everyone know where everyone else is. Off we go then, I'll start â âI love to go a-wandering along the mountain trackâ¦' ”

What a row! Will couldn't imagine how Mr Frobisher could expect to hear where anyone else was above the din that he was making himself. And as to keeping spirits up� What if they met someone with all that noise going on? That would be really embarrassing.

The others must have been having a similar thought because, apart from the bellowing of Mr Frobisher and some enthusiastic squeaking from Osbert, the others remained silent. Silent, that is, except for the squelching of their boots and the rustling of their breathable, water repellent garments. This, incidentally, was quite different from the noise made by Mr Frobisher's canvas and oilskin outer garments. Had he been making slightly less noise by singing he might well have found the difference interesting, though he would no doubt have thought that the high-tech rustlings were inferior to the traditional.

Will let his mind drift back to the thoughts he was having before the interruption. The din up front reminded him that he should add music to his list of fairly uninteresting subjects. He quite liked listening to music â but proper music, not the kind that music teachers like to play in music lessons. Definitely not the kind of music involving accordions and bagpipes that the ancient Miss Pringle, the dancing teacher, liked them to prance around to. Miss Pringle was very proper. She would have corrected that sentence to âDefinitely not the kind of music to which Miss Pringle, the dancing teacher, liked them to prance around.' She would have then clipped one or more of them round the ear and got them to do it all over again.

Science, now that was what he really enjoyed. He thought that he would enjoy it even more if there were a few more loud explosions and bad smells. Biology was dull, all buttercup leaves and worms' intestines. Even some of those physics experiments where you had to dangle weights on springs and see how much they stretched were a bit boring. But he liked machines. Anything from steam engines to space rockets. One day perhaps he could be an astronaut, or invent a spaceship that could travel to distant stars, or a time machine, or a ray gun. Right now it didn't seem very likely, trudging along this wet mountain track with the cold seeping into his bones.

The mist was so thick that it was pointless looking where he was going so he thought that he might as well get his phone out and play with it as he walked. Then he remembered that the batteries were flat. Still, knowing that it was there in his backpack gave him a bit of comfort. It was nice to know that even if it wasn't working at the moment there was some technology close by in this wilderness. If he couldn't play with it at least he could run through some of the games in his head.

The singing stopped and after a few more steps Will bumped into the rest of the group who were clustered around Mr Frobisher. They all looked miserable but their teacher was all enthusiastic.

“Map and compass. The purest form of navigation. I know that you might think that maps aren't very interesting but out here, in the wilds, all those contour lines and symbols come to life. Out here you should never be without map and compass. With this map,” he waved an ancient â and slightly soggy â piece of paper, “and my trusty prismatic compass,” a contraption of glass and brass, “I can always find my way.”

Will perked up slightly at the sight of the compass. It looked an interesting device but there didn't seem much chance of Mr Frobisher letting go of it at the moment.

“Ideally we need some landmarks so that we can triangulate our position and then plot a course.” Some of the group started to look a bit bemused at this. For once Will was one of the few who understood what the teacher was on about. He knew how a compass could be used to find the direction to various landmarks then working backwards from this to work out where you were, but he doubted that many of the others did.

“Of course,” the teacher continued, “in this mist we can't spot any landmarks so we will have to work by dead reckoning. Just give me a minute and I'll have us on our way again in no time.”

Will thought that in the 21

st

century there was no need for all this messing about with map and compass. There were GPS systems: Global Positioning Satellites put up by rockets and orbiting the Earth. You can get a device no bigger than a mobile phone â or even get phones with them built in already â that will pick up signals from the satellites and tell you where you are to within twenty feet anywhere on Earth. Will's Uncle Harold had got one. It was fitted in his boat that he used on the canal. Never been lost yet. Mind you, since canals are more or less only there and back, Will thought that perhaps Uncle Harold wasn't using the GPS to its full potential.

Another stray thought entered Will's head:

mobile phone â I bet Frobisher hasn't got one of those either.

“Ah yes, well. Seems to be about right. Follow me.” So, holding his trusty prismatic compass before him, like a talisman to ward off evil, Mr Frobisher strode off once more into the gloom. The gloom, incidentally, that was getting even more gloomy as evening wore on.

So, on they all trudged. Ever upwards. Ever onwards. Ever wetter. And to the careful listener, perhaps Mr Frobisher's song was getting slightly less loud, slightly less confident. The rest of the group hadn't noticed yet but could it be that the pioneer was being replaced once more by the steady motorist whose routes were carefully planned around stops for refreshment and the use of clean facilities?

As the walk continued the procession became more spread out along the track with Will still bringing up the rear. He liked it that way. At this distance the teacher's singing was slightly less painful. Also, since Osbert was bound to be within three feet of Mr Frobisher, there was no danger of another lecture about sheep. Alone with his thoughts and now set in a steady pace as he squelched along, Will, although not exactly enjoying himself, was reasonably content and looking forward to a warm drink and something to eat at the end of this march. He had no idea where he was but thought that it couldn't be too far to go now as it was starting to get quite dark.

Wham! Suddenly Will was brought back to reality as something very hard and very wet hit him in the side, knocking him off the track. Stumbling to regain his balance he fell to his left and half sliding, half rolling, slithered down an almost vertical slope. His descent was stopped by his head hitting a rock covered in moss. His last thought, as he slipped into unconsciousness, was imagining Osbert's voice in his head saying

“Suffolk ram, rather unusual breed of sheep for this part of the country.”