Winnie Mandela

MANDELA

a life

Anné Mariè du Preez Bezdrob

I dedicate this book to my children

and to my grandchildren

to my mother

and to the memory of my father

and to the noble and courageous women who have been my inspiration

I

N HER POEM

‘Instead of a Preface’, my favourite poet, the Russian Anna Akhmatova, relates an experience during the years of Stalinist terror. She spent months queuing at prisons in Leningrad, where her friends and family were incarcerated. One day, a woman in a queue recognised her, and whispered into Akhmatova’s ear:

‘Can you describe this?’

Akhmatova said, ‘I can,’ and the shadow of a smile passed over the face of the woman with the tortured expression and blue lips.

The phenomena of political oppression and racism have mystified me all my life; and after encounters with war in Namibia, Zimbabwe and Bosnia, both as a journalist and a political official with the United Nations, the pursuance of war merged with my other prime field of interest. This has led to an ongoing study of the political history of southern Africa, the former Soviet Union and, most recently, the former Yugoslavia – specifically Bosnia, where I spent two years of the war during the 1990s in the country’s besieged capital, Sarajevo. Increasingly, my experiences led to the desire to describe what I have learned.

In my attempts to fathom the psychology of the oppressor, the warmonger and the victim, I have come to understand that there are mere degrees of difference between Stalin, Hitler, Milosevic, Karadzic, Verwoerd and other apartheid leaders. The same applies to the millions of people who blindly follow ideologies and doctrines that range from the immoral to a licence for murder and genocide.

I have also come to know that the human spirit can be temporarily subdued by terror and hardship, but never conquered, irrespective of the duration or form of the oppression. Women, especially, have a unique ability to retain their capacity for nurturing and joy, even during unspeakable horrors and loss.

My life has been marked by extraordinary experiences, and this book is the fusion of various strands, beginning in my childhood, with the invaluable gifts I received from my parents and grandparents. They were living examples of fairness, compassion and moral courage; allowed me the space to develop an individual and enquiring mind; and provided a sterling illustration of the importance of faith.

They laid the groundwork for everything that is meaningful in my life.

My father was bitterly opposed to apartheid, quite extraordinary for an Afrikaner of his generation and class. To him, all people were equal, the only distinction being between good and bad, and this was firmly stamped on the minds of my siblings and me. He defended his principles at considerable cost, but would have agreed with Olive Schreiner: ‘It never pays the Man who speaks the truth, but it pays Humanity that it should be spoken.’

My mother provided the first example of women’s ability to face difficulties and misfortune with grace, tenacity and humour, and still embrace life with delight. I have immense admiration for her strength of spirit and enduring efforts to overcome setbacks – even tragedy.

My grandparents were the salt of the earth, simple people with little formal education but great wisdom, and they weathered every storm and countless hardships with unflinching faith.

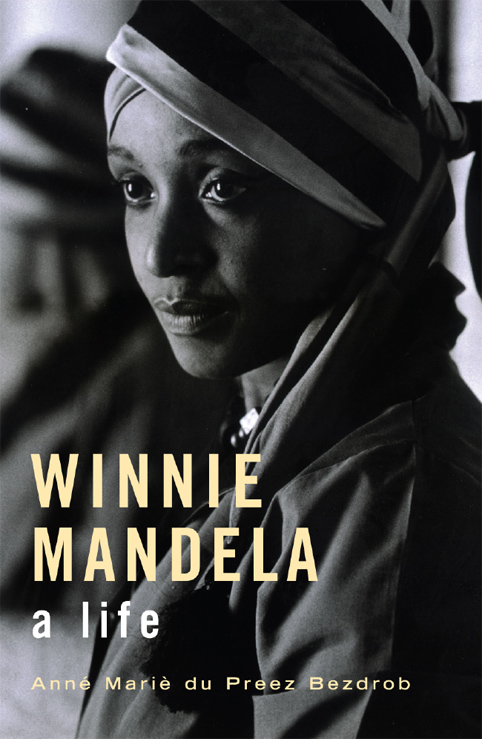

Some years ago, I saw photographs of Winnie Mandela in a magazine, and noticed that as a young woman she had lively, laughing eyes – the soulful, striking eyes many observers commented on. However, in later pictures, her eyes were mute, as if the light in them had been extinguished. That set me wondering what hardships had caused such a woeful metamorphosis. As a former political journalist, I knew a little about her, and I had witnessed the adulation that was showered on her in New York in 1990. Having encountered the unwelcome attention of the authorities and security police with my own opposition to apartheid, I had had a taste – albeit just a fraction – of some of Winnie’s experiences. I could relate to her as a woman, as well as identify with the loss of privacy, having your telephone tapped, being watched and followed, not knowing when or where the security police might pounce, worrying what might happen to your small children if some ill fate befell you – and being betrayed by the people you trusted, all the while knowing that you were at the mercy of those who needed no proof of misdeeds and had unbridled power. Add to that two years of full-scale conventional war, comparable on some levels to the situation in South Africa’s townships, and my apprenticeship was complete.

From the outset, this book was intended to be more than just the story of a remarkable woman or of South Africa under apartheid. I saw it as a parable for the courage and compassion of women in war, and the effects of ruthless dictatorship: the brutality of unscrupulous leaders struggling for survival, and the enslavement of man, whether in southern Africa or the former Yugoslavia. It makes no difference whether the oppressor is white or black, Cambodian or British, Muslim or atheist – the consequences are the same. What is disputed, stolen and destroyed is not land or mineral rights, but the individual’s right to personal freedom and self-determination.

During the war in Bosnia, I got to know many women who were living symbols of opposition to Serb terror. Their resistance was not chronicled in poetry or

embodied in political activism; their resistance was life itself. The entire world thought it impossible for Sarajevans – besieged and virtually unarmed – to weather the Serb onslaught and stay alive for more than a few weeks. But for four years, Sarajevo confounded the Serbs and astounded the world. And it was the women who provided crucial support for the vastly outnumbered and outgunned defenders of Sarajevo. They walked for miles and queued for hours for pitiful handouts of food, and carried buckets of water through heavy shelling and gunfire. They buried their children, their husbands and parents, and continued living. As their homes were bombed and burned, they retreated to a back room, or someone else’s house, and continued living. They wore their best clothes, put on make-up, and laughed. My friend Gertruda Munitic, an opera singer, kept singing for the people of Sarajevo amidst the deafening roar of exploding bombs. My friend Jasna Karaula, a university lecturer, walked miles and miles in defiance of Serb snipers to deliver life-saving medicines to the sick and wounded. My young friend Anja Kerken, teenage daughter of my neighbours Mima and Seo, did numerous things to make my life more bearable, and walked to within metres of the front line to collect precious firewood for their household. My admiration for these women is total, as it is for the women of South Africa, Liberia and Palestine.

Winnie belongs to this unique fraternity of extraordinary women, most of whom will remain forever nameless. They live, or have lived, in Bosnia, Zimbabwe, Israel, Nazi-occupied Europe, Myanmar, the Congo, the Soviet Union. Many of their names are interchangeable with that of Winnie Mandela – or Anna Akhmatova. Like Winnie, Anna, too, was beautiful, courageous and enigmatic. And, as she pointed out in her poem ‘Requiem’, she, like Winnie, suffered not in a foreign country or under a foreign power, but among her countrymen. Winnie Mandela, like Anna Akhmatova, was where her people, unfortunately, were.

What the author Joseph Brodsky said of Akhmatova applies equally to Winnie: she never resembled anyone. Though born half a century and half a world apart, both their lives were governed by the controlled terror of a state that tolerated no opposition. Akhmatova’s first husband was executed for anti-government activities, many of her friends fled into exile, others – including her son – were imprisoned in Stalin’s terrible jails. Her poetry was banned, her dissenting voice silenced. As government changed hands from Stalin to Krushchev, Akhmatova was briefly hailed as a heroine, then again denounced. She kept writing, keeping alive the memory of the millions of victims – as Winnie helped keep alive the struggle against apartheid. These qualities apply equally to the many courageous women I knew in Bosnia, and no doubt to Aung San Suu Kyi in Myanmar, and the millions of nameless women who choose to confront oppression and injustice when it is safer to turn and look the other way.

Elie Wiesel, who survived Hitler’s holocaust and dedicated his life to exposing Nazi war criminals, wrote these powerful words:

The opposite of love is not hate, but indifference;

The opposite of life is not death – but indifference to life and death

.

ANNÉ MARIÈ DU PREEZ BEZDROB

PARKHURST, JOHANNESBURG

SEPTEMBER 2003

‘There are victories whose glory lies only in the fact that they are known to those who win them.’

– Nelson Mandela, Long Walk to Freedom

T

HE WIND CHANGED

direction slightly and a sudden gust swirled around the cluster of men on horseback, wrapping them swiftly, unexpectedly, in the sweet, choking odour of death

.

The horses, eyes wide with panic, snorted in alarm, tossing their heads urgently from side to side. Two of the stallions staggered onto their hind legs, arching their necks to escape the pungent smell. The other horses started milling around, straining at the reins. With some effort the riders steered them downwind, out of range of the nauseating stench, and rode onto a small outcrop from where they had a view in the direction from which the wind had come

.

They stared at the ghastly picture below in shock and disbelief. Shrouded in a dense, tangible silence lay a scene of utter devastation. As far as the eye could see, the ground was littered with the carelessly scattered bodies of hundreds of dead men, women and children, cattle and dogs. Vultures squatted nearby. Thousands of burned elephant tusks added to the putrid smell. The earth seemed to float on a flat cloud of dirty smoke. For miles around them the black, burned countryside was desolate; everything annihilated, laid waste as if devoured by a giant fire-breathing predator

.

Nobody uttered a sound as the small group of horsemen under command of Major General Dundas gradually moved closer, glancing in horror at what had been the Pondo Great Place, now nothing but scorched earth and decomposing bodies

.

This, then, thought the young Holden Bowker, was the aftermath of that overture of death he had heard for the first time the night before: the Zulu ‘war cry’, a never-to-be forgotten sound. It made his flesh crawl: ‘a shrill, inhuman, whistling roar that passed with lightning speed’,

1

suggesting the pace of death as it descended swiftly, mercilessly. It was midnight and they could see nothing, but knew it came from the charging army of Shaka, the Zulu king, as his warriors swept through the cold, coal-black African night

.

The small group of white men had gone to the aid of the Xhosa after months of attacks by Shaka’s Zulu

impi

, culminating in the attack on the Pondo Great Place. At the dawn of a new day they found themselves marching alongside several thousand

Pondo and Tembu fighters toward 1 500 of Shaka’s warriors. The two hostile forces converged on the flaxen winter veld in the pale sun of late winter. It was an ominous sight. Assegais and shields waved like branches in a giant breath of air. Across an open stretch of 150 metres, the Zulu warriors were resplendent in full battledress, their strong ebony bodies still and taut in anticipation of the fight

.

The Zulu were outnumbered and there was a brief, bloody battle. The white horsemen formed a flank of the attacking force, but Shaka had been advised not to engage the whites, and the Zulu fighters avoided them, retreating to a hill further away where they regrouped and awaited the pursuing allied Xhosa force. Another bloody clash followed. Brief, brutal. Again the Zulu

impi

retreated, leaving behind a large number of the cattle they had looted in their raids on the Xhosa. On the battlefield lay three dozen dead fighters, half of them Zulu. The Xhosa decided to let the retreating Zulus go, rounded up the cattle and went off in their own direction

.

The small group of white horsemen feared that the Zulus might return, and knew they could not stand against them without the help of the Xhosa army. They turned back to the colony, relieved to be heading for the safety of their homes, trying to forget the images of death and devastation: the dreadful mutilation of small children, limbless women, slaughtered animals, the giant fingerprint of unmitigated and merciless destruction

.

After riding for the rest of the day they offsaddled and started a fire, grateful to be on solid ground. They took some meat from their saddlebags, and stood around the fire recounting the journey and the battle while the delicious odour of grilling meat intertwined with wood smoke and curled into the gathering darkness. They were hungry, and waiting for the meal was bittersweet

.