Women and Men (160 page)

Authors: Joseph McElroy

—laid out? asks a voice threatening to get comic that instantly acquires the body of the all-purpose interrogator who has probably picked up "all-day sucker" in his crash research for potential enemies’ childhood laid out with a jawbreaker roundhouse right—but no: not laid out on the carpet with one punch, laid out like a ground plan in motion—

—so later he knew that that morning that his always beloved grandmother had been off there waving away the distance between them like thin air, he had put away into a dump of his brain some sketch or letter in the seldom-emptied wastebasket in his own room two doors down from his father’s bedroom (pyjama’d forty-five-year-old bulk dead to the world in sky-blue cotton issued him for his July birthday till that father would come awake jerking up onto one elbow and shielding himself with the other against the room’s deep shadow so Jim could quote his father’s old "He’s a good boy when he’s asleep" remembering many not apparently unhappy bedtimes when this got said in his mother’s company but when company was present so the smaller Jim would grin dumbly, he saw himself, but no one in this dark bedroom to say it to now, and so much surrounding the now bigger, older Jim inside that it’s worth putting also out of mind), a diagram (close to) a coach’s blackboard play-pattern remembered (doodled) with an exactness honoring maybe not the scale or content but the method of the October History class he was sitting in; or during Geometry; or during Journalism (which, oddly, his father with all that practicality sweating toward acumen if not quite to it, didn’t think he should waste time taking when there’s a newspaper in the family:

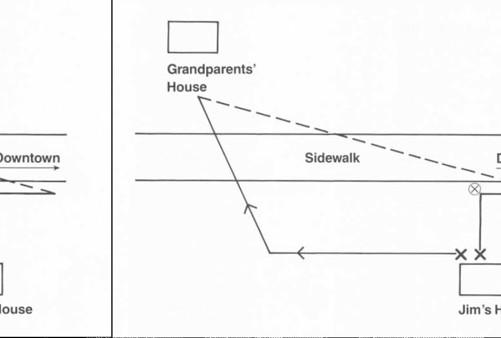

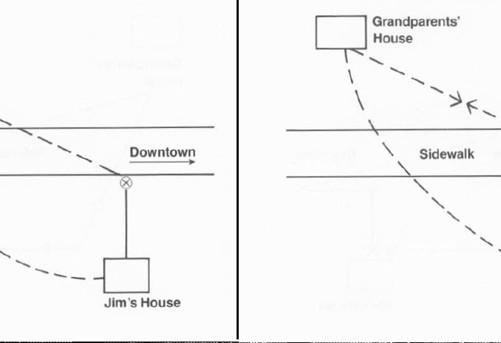

: so the lines of two homes got linked by a street paralleling them by means of sidewalks the length of the town, and got connected by him and corrected by his heartbeat so that, shifting through at least one inequality, they became like the lines of one T-formation halfback going in motion to the left side until the ball was snapped, and the quarterback faked a quick pass shallow to the left but he handed off instead to his stellar fullback (me) who went three steps to the right, leaned toward scrimmage—toward tackle, where a void had been cleared by "Tornado" Tim Ivins, thus attracting doubly a new flow of enemy defenders—leaned the other way to cock his right shoulder and heave a surprise pass as unexpected as it was diagonally risky to the far left sideline where the very halfback who’d been in brotherly motion and to whom the quarterback had just faked a pass was now all on his lonesome, while drawing during History your circled Xs and your broken lines and the blocking assignments, he was aware of growing a rollicking hard-on receiving beside him his girl’s faint halo (just before lunch) of gentle sweat and a seasoning he knew one night some weeks later was gardenia. He had brought her one, having never knowingly smelled one, in a shiny white carton, shoebox size, he had to carry like a coffin offering with something live or afloat inside, gingerly anyhow, and dared to greet her with a kiss upon her cheek but long enough (was it one kiss, or two or three) so he felt her smile but with precious quakes along the dimple which are now and forever tender plus amused, so that (in any event) the play pattern of the quarterback’s faked pass and the fullback’s faked run displaced the teacher’s words—which were

about

words—and well this was the way the diagram of the two homes acted like a play pattern and that early morning that he felt was brought to some wonderfully imperceptible point upon the raw air by his grandmother’s being there,

he displaced or slipped into a fold of some soft luggage for the journey (Great day in the morning! his granddad could say, happily astoni’ed) which fold might have been itself something slipped away—

dis

(we continue)

placed the atmosphere of seeing his grandmother waving,

in the time it took him to go from porch down own front walk to sidewalk, his own home behind him had obviously swung round (but don’t tell anyone, they’ll say you’re nuts or, worse, that you’re not serious, don’t tell even yourself, for, shit, the truth’s gon’ come out anyway)—sailing before those prevailing easterlies you heard about

{prevailing westerlies,

a man interjects at seaside Mantoloking cripes anybody ‘n everybody knew what west wind meant!). But was it blew

from

or

to

the west? because Jim asked and forgot—to think about it, that is—and asked again

{and

wasn’t told!) for they didn’t even know all about clouds and you could see clouds but couldn’t see wind (said some voice in him) and this was there in him and yet wasn’t him at all because he was on the march to school: he blew up at his girl (though laughing all the way) Whadda ya mean I’m spoiled?—just ‘cause you say you got homework so you can’t come out to the movies?—and he squirted—

—quite unexpected words at her: "What if you got pregnant?" (he would say anything to her at fifteen, he could do that and she didn’t get shocked) but he was thinking horrified a second, What if this queenly girl has

already

(not

gotten,

but)

been!

—and never told me!—because some girls must be like

that,

‘stead of putting the screws to you in which case you followed Owl Woman’s example, "I am going far to see the land, / While back in my house the songs are intermingling." But if it is not an irreverent interruption, How did owls get a reputation for knowing so much?—shit, Owl Woman, according to the Hermit-Inventor of New York who heard it from several people including both Margaret and the East Far Eastern Princess, was just always turning

into

an owl and her getting the name (they took all the good names—Red Cloud, Left Hand, Reared Underground, Tall Salt)

Owl Woman

might not mean a thing about wise owl shit and mean only that she disappeared into an owl when she wanted to and maybe flew around at night looking for bright eyes to aim at until—

CUT

—she was back again Owl Woman, singing songs she didn’t claim responsibility for since they came to her in dreams or when she was an owl but who was to say if the owl was in her or she was in the owl, or basically

was

owl?, she was known to have had children, so maybe she wasn’t an owl; but what happened if you turned into an owl in the middle of giving birth or in the middle of—

—squirting water he had virtually sucked (so distant was it) at the old low-pressure drinking fountain outside the noisy school cafeteria at his friend Sam’s big brother who wore glasses lensed thick as whirlpools and was fat enough to sit on you but when fighting threw these fiendish longitudinal jabs that looked fast but no more than fast until they went through you as evil as an electric shock and permanently greened a muscle in your arm y’know, and on the march to school (for, after the million shocks flesh is heir to, it’s still only the late apple-breeze of the fall of 1945 with the dust still setting on those immortal Japanese recreations one beginning

Hiro

t’other ending

saki

that through their layers of sifted, screened, pastel’d tumuli-cumuli foretell that with American aid the Japs can imitate anything, up to and including an obliterated polis) it’s his grandmother just beginning the day sweeping the porch a bit early, not this daydream of his own front walk maybe twenty or twenty-five yards behind him turning into that other and only apparently much greater distance from him of her house so when he waved back far down the street and held her gaze a second as casual as if she was there

every

morning, the distances to either home with him at the center were, well, equal—her large gray eyes his body swung to, as close as his mother’s eyes sometimes at the window behind him of his own house that’s turned by this arc of mind or swing of wind to his grandmother’s: This afternoon in his mind anyhow he would be fighting the halfbreed (who most of the time had no smell) for the halfback spot that in the new formations was basically left halfback when everyone knew that he should and would stay where he was, he was broader and right for fullback where the coach was playing him for sure-footed solidity and while his grandmother, who often employed that halfbreed classmate of her grandson’s for yard work, asked of the "endless hole," as grandfather put it so slowly filling up with doughnuts or crullers, how football was going, or Sam’s father’s huge greenhouse for commercial roses, or how Geometry was going, she would listen so truly to what was said that she might have been drawing out of him those shelved daydreams where the halfback’s positioning and speed went apart from his person, in fact so perfectly separated from the halfbreed’s braggart person that you acquired your own signal back at you that, on a morning porch not obscured now by the bough leaves of other months and from the center where you yourself were just equal in radius (that warmed and vanished into his hand’s question now

Which

was more sensitive—the upper slope of his girl’s breast or the lower plum-jut and did

one

breast get aroused by the other’s being aroused?)—just equal in radius to his distance from his home porch, because that porch of hers

was

home to him, and never forget that if he himself had lost his one mother (by sea; one if by sea), the grandmother-woman had lost a

daughter

(which word he could apply to his mother only with the difficulty he had of thinking she was not dead), and if he couldn’t think of his grandma generally and of his girl’s breast in the same head, nor with the real regular stuff on his mind and at the same time that dopy radius that belonged in someone else’s mind not his daydreaming its swing around behind him and in front of him plotting out some future, and then around and back between the obviously near house his father now alone owned and the grandparents’ place obviously six, eight

times

as far away (leave the surveying to us, to George Washington and his sister city Thomas Jefferson), why the radius from being impossibly the same to both houses to being plausibly and clearly the same now became a radius just a shade more than you needed or wanted: but for what? for some godforsaken reason that forgot itself in the doings of his day till he paused at the threshold of a class early in the darkening afternoon and got shoved with initiative by some class799

mate just as he saw rain hitting the silver panes like light, and his teacher, a statuesque woman capable of movement, turned from the board with wet around her eyes und cheeks, so that, elbowing the friend who shoved him, he could put all of it and none of it together for a second to embrace an elusive burial of fact, that it must be

many

mornings his grandmother had been on that porch of hers up the street watching the motherless brothers go to school in succession, and he had

known

it with some corner of both his eyes so not shifting their light upon her who watched over him was just this vacancy about the thing that had befallen him—not a death, though someone else’s, but a thing—fallen right through him to leave him nowhere to be found apart from the wave that had fallen through him, so there’s this feeling that’s unsure embarrassment (he told his girl Anne-Marie after they had lain on the night ground fifty yards from Bob Yard’s parked pickup truck, and she understood how you could

feel

embarrassed at

being

so) over what his mother had done or "arranged to have done," he kept hearing and hearing, though this he did not report to Anne-Marie, layin’ on her elbow once in a while noticeably blinking with the coolest and most loving concentration so that he finally cried one time there on the ground and said he didn’t know shittin’ why except he was now

more

than embarrassed (she said, I know), he shoved her in the shoulderbone, scented flesh, matter!—and she shoved back harder and he almost asked her to marry him by which he would have meant go away now at the age of fifteen and a half, which she would not have done and partly because she did love him, but he didn’t say the words and felt better for holding those words in, while sensing the Tightness of feeling, yes, embarrassment (it didn’t matter if anyone else in the world felt it for this type of event—

he

did) embarrassment at the departure of his mother, his grandmother’s daughter; at the same time he was not going to go out of his way during that autumn to tell his grandmother he couldn’t trust her old Princess and Indian stories to be stories any more because she was obviously often the East Far Eastern Princess and had done at least some of the things that some of the time some of her old kid stories said, an Indian chief’s son’s mother who was nuts or at least with a hole in her head all the time filling with demons really did die

and

really did come back to life when her son left in pursuit of that paleface Princess now immortally bronzed by the western sun (though bronze was an alloy of Bolivian tin and Chilean copper, though come to think of it, how

did

you alloy? did you melt the metals and stir ‘em up in a bowl made of earth?) and somewhere in his mind populated by football smells of cleat-rubber, fresh (green) football shirts, hide, choking earth, and the tense, constant future of play patterns and populated by his now only one girlfriend’s wonderful proof that flowers might perspire with dew that other scientists could imagine came down from above and from the outside but really came from the interior of the soul even on Sunday to the straw-creak of slightly shifting cushion stuffing in the church pew (that seemed the least Godly place of the week and in some pleasant threat one of the more exclusively sexed-up of times in the fairly steadily sacred week, feelings he years later knew that he had accepted as wordless and unlosable), he recalled and recalled that his mother had told him he should go away and would go, but then had gone herself: so he woke up into his mother’s oceangoing hallucination for which there was no word, not even the one they gave it beginning with

s

(for

selfish,

for

sea,

for

simoom,

for

suing

in absentia), too confused to do any but the next thing, suspecting that his grandmother’s west-easterly histories shed upon him some shadow if he let them (which he did not do) imagining through the successive fall and winter clarities of his mother’s absence that no force acted on him, oh he was freer (oi, he was freer—oi, they would say, because one of their friends was Jewish and both his parents were, too, in that New Jersey town and this kid’s father had bought out the hardware store and enlarged it just at the time another newspaper got started that commanded the outlying agricultural advertising and audience, oi), freer than free, which equaled but an illusion of manhood he even then guessed.