Women and Men (203 page)

Authors: Joseph McElroy

Well, Mayn had gray hair when he married Joy, but gray hairs or not, the two of them had been through the wars together. That was what Mayn said. Said about her, she felt, as if she had often been one to start whatever they had then been through together. But didn’t Joy say it too? Said it to her friend Lucille. Been through the wars. So? Yet sometimes it had seemed like nothing, like the gap between JFK at 9

P.M.

and San Francisco at—actually —midnight Pacific Time, and one year it was

one.

Blanched shadows receding off to the left along the Rockies visible under the plane’s own moon. Not wars at all. An evening out, days at home—in tune—nights away from home subtracted like bad behavior as if they didn’t count. Not wars. More like falling away from time, falling through your own vaunted resilience, through nothing—but falling. Falling upward, even. And at home as well as in a hotel. Falling out of bed at dawn so your fall was broken by the ceiling. Jim. For Joy didn’t do that sort of thing, her daughter pointed out to her, product as she was of them both.

The void lets out a smile, which he and she might feel as a breath of relief somewhere that what had happened to them could be said so.

Been through the wars. A common breath let out like deep thought that was the two of them or nothing, and much heavier stuff and finer and more subtly worked out than either of them could have thought, such intellects as they were.

Been through the wars. A real-estate hot shot (though nice guy) named Sid living with a girlfriend now, and one day on the tennis court got a phone call from his doctor asking him to come in, and they decided he had two types of cancer, one possibly they couldn’t do anything about, the other his lung, and because his former wife, who was a lab psychologist working with animals, had smoked (at him) for years, he went looking for her and found her at dinner at the Mayns and told her, no less: but no one did anything, including him. The children were in bed.

The void will calm things down. Speaks through you like a whole thing of force and membrane neither yet full-grown. But in the person of those whom that void after all keeps moving, the void disperses time and the particles by which it is told until the equality of all things can become too much and a drag. And the nick in the back of the head that shows barely through the hair is not only a blood type but a section exacted from a singular person who might need to be saved at the expense of someone else.

How he knows ahead of time when she enters a room—is it some throat clearing he has lent her as if she like him were dialing a phone number and getting ready to speak? or is it some warning she has lent him in a private smile he knows (and pays for knowing) is there around the corner of the hall doorway before she comes in sight?—and if he knows exactly tonight how their host will enter behind her, as if for the moment they two weren’t intimate kitchen-sympathetic. Has life with Joy made Mayn this way?

This knowing is like some out-of-character eccentricity; he’s an ordinary guy, for God’s sake (and God would rather he’d stop thinking that)—not much of a believer—and when they arrived a while ago and the host kissed Joy and shook hands, Mayn felt the presence of another woman who wasn’t there, a wife or woman paired with the host. He did have an ex-wife somewhere— though not somewhere in the living room—but the point about the host’s kissing Joy was that his absent woman was imagined by Mayn as sticking out her hand to Mayn, kiss balanced by handshake, well a pair of couples needn’t be symmetrical, need they? yet the messages don’t quit coming; and in a Windsor chair near the fire (the andirons too far apart, the chemical log sagging and collapsing to bridge its break with a blue-green flush) he gazes at the young detective in a blue-and-red ski sweater who’s cutting his law class tonight, who’s on the floor between Mayn and the fire talking equally to Mayn and Lucille Silver who calls him Rick and questions him and he’s responding so Mayn is getting a garbled message part of which is that (which he knew already) he brought the detective here tonight and brought him like a message unknown to the bearer—well, Rick is in an A.A. group with a free-lance frogman Mayn knows, and Rick is cool for his age, his cheek crackles with shadow and color, so (Rick’s saying) he’s got nothing but respect for that guy’s homicidal instincts—so—so—so Rick (he’s saying) is about to get hit over the head, right? so he’s standing in the street telling the kid in the big white T-bird to put that thing down, but there’s someone

behind

Rick—Lucille crosses her legs in the corner of Mayn’s left eye and a flow of fleshly concern—flesh turned to fluid—gets to Mayn as Joy, having come in, falls cozily into her chair to his left across the white room, knees together sliding together off away from him as if she would tuck her feet up under her in his direction; Joy grasps Rick and Lucille in a look that opens like her lips which part—Rick and Lucille, who’s half again Rick’s age and twice as present to Mayn as Rick is to Joy (Mayn’s sure) . . . and when Mayn (who doesn’t seem watchful) swings his head a little toward Joy she seems to open her eyes in a glance that bears so much condensed attention out of the past so completely and painfully but, for a flash, so entertainingly to him: for example, Lucille likes more danger than the young cop knows (for, according to Joy, Lucille has twice disarmed her son—yes, literally—his father taught him to shoot a big .38 and ordered him never to carry a pistol), but Lucille doesn’t like risk quite so much as she is thought to by Jim, who likes her O.K. and distrusts her more than she knows because he confides in her once in a while. Joy’s teeth show but her tongue crosses her lip and time halts in her face as when one of her children takes a long look at her, a radiant thought that wished its way there from elsewhere in her body because a blankness at once slipped over Mayn’s eyes large enough to include the extra wine glass she has carried in here and has set down on the table beside her first glass—doubling that prior silence out in the kitchen beyond the living room that Mayn has received like rays passing through these minutes of the young policeman’s choice tale. Until a hatch falls in and all the objects in the room course into the foreground, into his eyes but not Joy’s, and there are for him no people, just objects and the space to go with them. But Joy’s tongue tip and a glint there on the lower lash of one eye give Mayn the fine word from her that please believe her whatever he thinks is going on it’s not public, what’s going on between her and the host—Mayn’s nameless witness won’t name him; Mayn

is

the witness—the host, the glowing, controlled man, has followed her not quite soon enough into the room and at once turns her from the cop’s rendition to tell her her father was smart to give her Texas Instruments in ‘57 even if she didn’t get along with him—but is this a tribe sitting here in this room? is this what it is? Mayn has the words ready to ask—and is he one member of the tribe and Joy another member (whose father if you want to get technical once in his cups threatened not to give her away) and Lucille and the policeman? And the man? The man’s name is Wagner and his place of work is some huge association where he keeps an eye on the pension portfolio. An "inside dope-ster" Joy called him to Mayn, and Mayn had heard it before, from someone else. Or in advance from Joy’s mind. Mayn wondered how much of Joy’s and his own story she’s put into words for this Wagner, and while Lucille, a friend in need, is asking Rick’s hours, saying married people see too much of each other, that’s Jim and Joy’s secret, Mayn drifts toward Lucille like his smell but his smell become conscious reaching her thoughts, and he says— out it comes—"Aren’t you a bitch." Yet Lucille seemed sincere in what she just said; and later when Joy bawls him out because Lucille is one of their close friends, he knows she’s instinctively getting away with it because, though it was true if not visible, he’s had that and can pay for it, and for a moment he and Joy are crazy together, though in a Connecticut motel next week he wakes to a Kansas City motel near the river, near the market too full of very raw animal-carcassed buffalo fish, and will never see Lucille Silver again because he’s kissing her goodbye, having told her in this dawn dream, for he claims

not

to night-dream, that for an offspring (like . . . what’s her name? . . .

Flick)

to have your courage shot into orbit by the dual thrust of united parents inc. is a great thing indeed unless the launch pad is unfinished or otherwise incomplete, and then for gawd’s sake don’t look back.

Their story covered many years and it was that Mayn spent too much time away. It even once got called that—a cover story; she’d said it to him in a letter while they were still married. (He remembered it when he took his daughter out to dinner some years later, she wanted him to sign a petition to get a Philippine writer out of jail. Jail? It might as well have been the Death House!)

He knew a handout. Some of his work was taking press handouts off a counter or desk in a busy room as far away as it was familiar and nondescript, handouts that were sometimes little more than a friendly pitch Xeroxed off an electric typewriter hustling a product (this was the point), and a newsman could put these handouts on the wire more or less condensed. But he would also go after assignments where you didn’t get a handout because what there was to peddle, to get onto the wire, wasn’t immediately clear, though he didn’t believe in what wasn’t clear, and he kept after the briefing officer of a natural-gas company who would turn away from figures like 7.5 trillion barrel-miles of various gas liquids and anhydrous ammonia being carried through more than two thousand miles of pipeline in 1961 to the claim that this firm was a "future" firm operating in a frame of reference not less than Energy itself and Related Earth Resources, and how can you be anti-Energy? you might as well be anti-American. Joy understood what he tried to do and liked him for it.

In May of ‘60, no longer working for AP, he did with the government story on the overflights what the story did, or said to do. With itself, that is.

Routine report: pass it on.

Mayn was like any company man or stringer.

So Powers, the pilot, was photographing weather—or (like a mechanical part of him) the plane was photographing weather; and the flights over Russia were routine weather observation—NASA said so. Now Mayn knew—or figured—that the story wasn’t true, and he had heard that it was not true from people who ought to know but also from a man he didn’t like named Spence for whom the extreme altitude of the slender U-2 plane gave to it, gave to the plane’s glinting eye, an exponent of threatening force, a light too powerful to see with the naked eye unpeeled.

Ray Spence was far away but approaching Mayn in the form of Mayn approaching him—that’s what Mayn felt. Well, people weren’t always credible.

Spence told Mayn back a story Mayn had told him about the newsman who got the jump on everyone else at the explosion of the Hindenburg. Mayn mentioned this—that Spence had told Mayn back his own story—and Spence laughed, but too long and softly as if it was understood Mayn had made a curious joke. "How’s the family newspaper?" he then said. "Got any good numbers in your book?"

But the government overflights story which everyone knew wouldn’t stick made Mayn, who was fed up with words within words, curious instead about the weather. What had NASA to do with weather and what was there to know?

So he was in Florida and later he was in California. Not into space he said—not space, not science—not ESP—and you could throw in the Fourth Dimension (and he didn’t mean the bar in Brussels of that name for he had a quizzical way of showing off or the book store in Dallas). Weather satellite —that was the size of it. No, not science—as Joy should know, who knew him.

You called the satellite a grapefruit. And all he was seeing was exactly how a four-pound grapefruit covered cloud belts across a quarter of the Earth. Then talking to the Coast Guard. Aboard a white weather ship about to leave for the Bermuda Triangle. Tall, thin meteorologist in the weather shack up on the boat deck facing aft, a Texan (‘‘originally"), with a German uncle in Chile multiplying bees. A German grammar on a folding chair on the rolling deck. A man in khakis with a bad black Texas mustache, no kidding, and an unconvincing habit of in the middle of his talk to Mayn calling out, loud and jolly, to any kid who came by with a wire brush or an electronic technician’s tool kit, then one who materialized below on the quarter-deck photographing a huge seagull standing on the rail. A global network of weather stations. Mayn could get into that. The man with the mustache lent him a manual which Mayn read and forgot about and later decided not to mail back from New York after the cutter had put out for weather station. This global network looked so compact, but put yourself in it and your neighborhood is endless. This thought followed him, not he it.

Up?

The curvature of space he would leave to other minds than his.

He talked to Joy about the weather. So then he’d be unable to explain his interest in it. That is, to her—at least when she said, "But blue sky in the winter in New York—but in Chicago over the lake, you’ve never seen how the water goes up the sky, it attracts the horizon, it lifts it, my father used to say—why, meteorology—what do these guys know?" ("I

know,

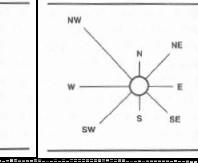

I tow," said Mayn.) "What about rain against the window—" ("Don’t be an idiot, Joy.") "—against the window the summer we were at the Cape playing Monopoly?" "Look, Joy": he drew her a wind rose: