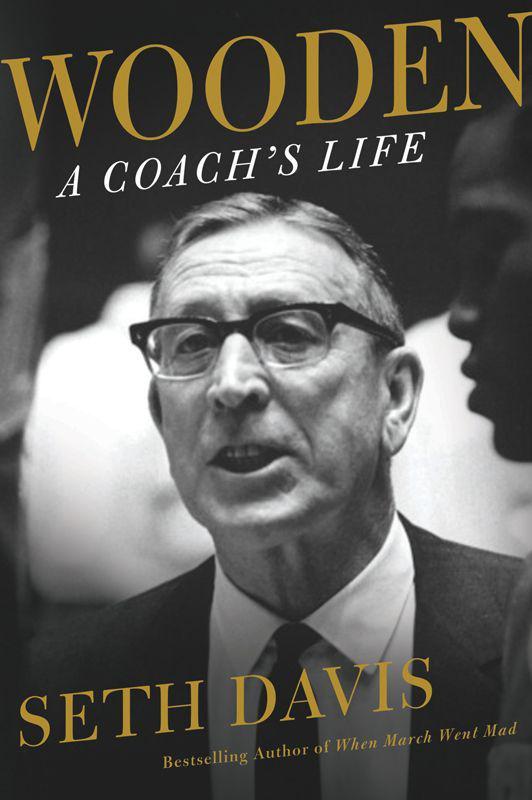

Wooden: A Coach's Life

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

For my teachers—

Zachary, Noah, and Gabriel

C

ONTENTS

John Wooden’s Coaching Record, 1946–1975

“I’ve always said I wish all my really good friends in coaching would win one national championship. And those I don’t think highly of, I wish they would win several.”

—JOHN WOODEN

PROLOGUE

The Den

The first thing you noticed were the books. Big books, little books, picture books, children’s books, art books, religious books, coaching books, sports books, fiction books, science books. Before I walked through the door, they were there to greet me in tall, neat piles in the front hallway. The books were stacked on floors, lined up on tables, piled on desks, jammed into bookcases. The apartment was barely two thousand square feet, yet it seemed that most of it was covered by something that could be read.

John Wooden was careful not to trip over the books as he made his way to his favorite easy chair in the den. Another dozen or so stood on the floor beside the chair, lined up as if on a shelf. The coffee table that sat in front of the television was likewise covered, a source of irritation for a man with a compulsive need for order. “Organization was one of my strengths for a long time, but now just look at that table with all that stuff on it,” he said as he invited me to sit on the couch. I asked Wooden how many of the books in that room he had read. “Maybe half,” he replied. “But I’ve browsed them all.”

It was September 2006. Wooden was not quite ninety-six years old. Even at his advanced age, he was still a student of the world, eager to collect one more crumb of wisdom that he could dispense to the next friend, interviewer, former player, or stranger who came calling. Though his eyes were not as good as they used to be, and though he tired easily, this old widower still turned to books during those rare, quiet hours when he didn’t have a visitor or the phone wasn’t ringing. Besides keeping him company in the present, they also served as a tether to his past, a dog-eared monument to the person who influenced him more than any other: his father, Joshua Hugh Wooden.

Hugh, as he was known, loved reading, both to himself and to his children. Though he did not have any formal education past high school, he was so facile with the English language that when he did crossword puzzles, he invented ways to make them more challenging. “For instance, he’d do it in a spiral form until he’d end up putting the last letter right in the middle of it,” said Billy Wooden, John’s younger brother. After a hard day’s work, Hugh loved nothing more than to sit down, crack open the Bible or another book, and read poetry to his four sons by the light of an oil lamp.

“I can just see my dad as I see you, if I close my eyes,” Wooden said, doing just that. He channeled Hugh as he recited:

By the shores of Gitche Gumee, / by the shining Big-Sea-Water, / stood the wigwam of Nokomis, / daughter of the moon Nokomis.…

Upon completing the verse by Longfellow, Wooden opened his eyes. “We had no electricity, no running water. He would read to us from the scriptures practically every night. For some reason, of all the poems he read, that’s the only one I can just picture him doing.”

When he laid down his books, however, Hugh did not have a lot to say. “He tried to get his ideas across, maybe not in so many words, but by action. He walked it,” John said. Hugh didn’t lecture his boys so much as he sprinkled seeds along their paths. When John graduated from the eighth grade, Hugh handed his son a small card upon which he had written his “Seven-Point Creed.” John later carried that piece of paper in his wallet until it wore out, whereupon he rewrote Hugh’s words on a fresh card. After he retired from coaching basketball at UCLA, John had the creed printed up on slick plastic cards and handed them out so others could plant Hugh’s seeds into their wallets as well.

The first of the seven points paraphrased a line from

Hamlet

: “Be true to yourself.” Number four read, “Drink deeply from good books.” So John drank. As a young boy growing up in Indiana, he dove into the

Leatherstocking

tales and Tom Swift series. His favorite teachers at Martinsville High School were his English teachers. When he attended Purdue University, he became close with Martha Miller, an elderly librarian. Once, when he was coaching basketball at UCLA, Wooden was so taken by the enthusiasm evinced by a guest lecturer that he wandered into Powell Library to read more on the topic. He devoured Zane Grey’s westerns and Leo Buscaglia’s motivationals. Though his all-time favorite book was

The Robe

by Lloyd Douglas, his interest was truly piqued by books about his favorite historical figures—Winston Churchill, Mahatma Gandhi, Abraham Lincoln, Mother Teresa. He lost count of how many books on those last two he had received as gifts.

Then there were the poets. Dickens, Yeats, Tennyson, Poe, Byron, Shakespeare. Especially Shakespeare. In college, Wooden spent an entire semester studying

Macbeth

, followed by another semester just on

Hamlet

. His favorite sportswriter was Grantland Rice, who penned many of his columns in verse. Besides being the coauthor of nearly two dozen books, including four children’s books, Wooden was himself a prolific amateur poet. An idea would strike him on his morning walk, and he would come home and scrawl some doggerel. He watched John Glenn orbit the Earth and Neil Armstrong walk on the moon, and he wrote poems about how those events made him feel. He set a goal of writing one hundred poems and assembling them in a compendium for his family. He structured the book into five tidy parts that reflected his love of balance: twenty poems each on family, faith, patriotism, nature, and fun. Even when he was well into his nineties, Wooden could still recite scores of poems from memory.

During the final years of his life, Wooden received countless visitors in that modest, book-strewn den. In between tales of championships won and players coached, as he recounted the fascinating twists and turns of his long life, Wooden would invariably bring the conversation back to the man who raised him. When he closed his eyes and recited Longfellow to me, his mind was transported back to the farm. But if it felt like a full-circle moment, it really wasn’t. You can’t circle back to a place you never left.

That, in essence, is the story of John Wooden’s life, a quintessentially American tale that spans nearly a century. More than anyone else, he could appreciate how his story neatly divides into four balanced seasons. During the spring, our protagonist takes root on his family’s spare midwestern farm. He alights as a young adult in a glamorous town by the Pacific, reaches prodigious heights of fame and glory in middle age, and derives warmth from relationships old and new that sustain him during a long, peaceful winter. Like so many great narratives, the accepted version, the one Wooden himself told, often diverged from fact, as the myth overtook the man. But when all the glorification is stripped away, the person at the center of our tale remains very much the same boy who was planted in the Indiana soil at the turn of the twentieth century. All those friends, interviewers, players, and strangers who came to that den the way I did, we all wanted to know the same thing:

How did you do it?

He could never make the answer clear enough, perhaps because it was too simple for a complicated time. Everyone wanted the old man’s secrets, but he had no secrets, only seeds. For all the things that John Wooden accomplished—as a player, a coach, and most of all, a teacher—he never forgot his roots, or the man who planted them.

PART ONE

Spring

1

Hugh

John Robert Wooden enjoyed unparalleled success as a college basketball coach, and after he retired he built a veritable industry around his own personal definition of

success

. Yet the most lasting impression his father made on John was the manner in which he responded to a failure.

It happened in the summer of 1925, when John was fourteen years old. John, his parents, and his three brothers were living in the tiny town of Centerton, Indiana, on a sixty-acre farm they had inherited from the parents of John Wooden’s mother, Roxie Anna. They grew wheat, corn, alfalfa, potatoes, watermelons, tomatoes, and timothy grass, which was used to feed cattle and horses. The town had few amenities—a water tower, a general store, a grade school—and the Woodens’ life was not easy. But they never wanted for anything, so long as they were willing to work for it.

If they needed bread, Roxie baked it. If they wanted butter, Hugh churned it. If they needed water, they hand-pumped it from a well. When winter came and the kids got cold, their parents would heat up bricks on the stove and wrap them in warm towels. If they wanted to relieve themselves, they used the three-hole outhouse in the backyard. The family got eggs from their chickens and milk from their cows. They started off every morning with a hearty bowl of oatmeal. The house had just two bedrooms, so the brothers slept two to a bed. “We didn’t have much money,” Billy Wooden said. “Father worked for a dollar a day in the twenties, but ours was a happy family. We were always having company.”

The setback came shortly after Hugh purchased about thirty hogs from a local farmer. Hogs were expensive, so he had to borrow money from a bank and put up his house as collateral. Hugh needed to inoculate the animals against cholera, but the vaccination serum he purchased turned out to be defective. All the hogs died. That, coupled with an untimely drought that killed off most of their crops, prompted the bank to foreclose on the farm. Just like that, Hugh Wooden’s sole means for supporting his family was gone.