Writers of the Future, Volume 29 (15 page)

Read Writers of the Future, Volume 29 Online

Authors: L. Ron Hubbard

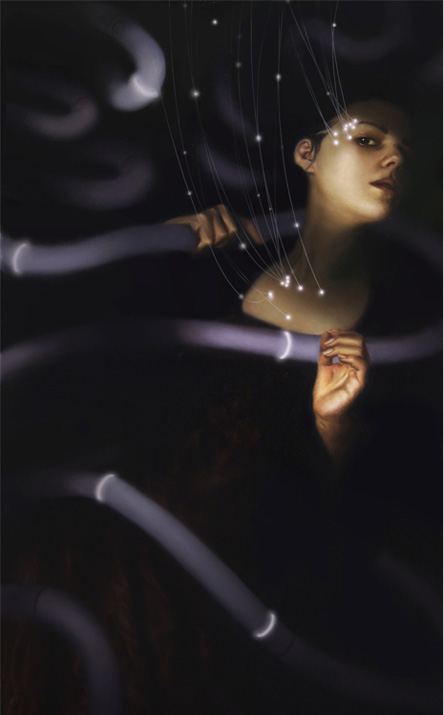

ILLUSTRATION BY LUIS MENACHO

I clench my fists and throw myself at the door, scratching and clawing. My mind rages in blind panic as sensations assault me, but I force myself to focus on Ava. I have to save Ava. I yell at her to hang on and she stops thrashing. I grab an empty cage and crash it against the glass until it shatters. The door behind me buzzes and opens. A guard rushes in and pins me to the wall.

Ava lies unmoving on the table. I scream for the guard to let me go, I scream about the missing halos.

When the guards check Ava's vitals and pronounce her dead, I scream that the doctor killed her, and then I just scream and cry and shake until Eddie shows up an hour later.

T

he doctors and researchers tried to explain to me their theories of how the redesign had affected patients' brains. Each of the patients suffered varying side effects as Dr. Reg adjusted the treatment, causing different forms of death.

The detectives found bullets in Dr. Reg's gun that matched the same slug that killed Sera Turner. Evidence recovered from Dr. Reg's email showed that Sera had been complaining of massive headaches, and threatened to expose Dr. Reg to the medical board when she discovered the treatments had never been approved.

He felt that he needed more time to complete his research. He became desperate for answers, and his unstable mind saw Sera as a threat.

No one could explain the missing halos or the short siphons. Dr. Ennis said that the redesigns left each individual's consciousness out of sync. Father Solomon said it was a sign that the victims' spirits were never guided into the light. I like to think that they have found their way now.

A

va's siphon has yet to be rendered. At first, I didn't want to render it, because I'm afraid of what I will see. Will her last memory be of me cowering in a corner while she begs me to help her? But I need to know one thing.

The frames are blurry and I spend hours tweaking and adjusting. Before long, I see myself rendered clearly, looking directly at her before I move away from the wall. I look determined as I fight to get to her. I look like a superhero.

The door behind me buzzes and opens.

Eddie comes into the dim room wearing his badge.

“Hi, Howard.”

“You hate Digital,” I say. “You said you'd never come back.”

“I know what I said.” He pauses, looking at the looping render. “It's lunch time; you need to take a break. I'm going down to Pierre's.”

I like Pierre's; they're next to the waterfront in a no-advertising zone. The crowd is usually small, lights dim.

“I'm not going to wear the goggles. You said I had to wear them.”

“Yeah, I said that.” He shifts his weight from one foot to the other. “You don't need them. You did good⦔ He chokes on the rest of the words and instead holds out his hand.

I think about the millions of germs on a human hand, how a handshake is so strange. I think about the sensation of touching, and Eddie's sandpaper knuckles. A statistic pops into my head about the percentage of people who no longer shake hands as a custom. Eddie waits for me, his hand suspended in the air.

I suddenly know what to do. I shake his hand, then leave without the goggles. I like being Howard.

I glance back at my desk as the door closes and pause long enough to see Ava's perfect halo fade to black.

The

Manuscript Factory

BY L. RON HUBBARD

Having now completed its first

twenty-nine years, the L. Ron Hubbard Presents Writers of the Future

Contest

remains true to the purpose for which it was

created: “To provide a means for new and budding writers to have a chance for

their creative efforts to be seen and acknowledged.”

Robert Silverberg, Science Fiction Grand Master and

judge since the Contest's inception, noted in recognition of the program's

success, “What a wonderful ideaâone of science fiction's all-time giants opening

the way for a new generation of exciting talent! For these brilliant stories,

and the careers that will grow from them, we all stand indebted to L. Ron

Hubbard.”

As one of the most celebrated writers during

America's Golden Age of pulp fiction, Ron began his career in the summer of 1933

in the California coastal town of Encinitas, just north of San Diego. There he

wrote and submitted a half-million words of fiction, shot

gunned out to a dozen markets. He saw sales from the start, with

his first published tale being “The Green God,” a routine story at the time of a

Western intelligence officer in search of a stolen idol. What made this yarn

different, however, was that the young L. Ron Hubbard had actually walked the

gloomy streets of Tientsin in Chinaâand in the company of a Western intelligence

officer: specifically, a Major Ian Macbean of the British Secret

Service.

Ron's rapid ascent to success as a writer can be

greatly attributed to the fact that his stories were drawn from genuine

firsthand experience.

This was best described in

October 1933, a few short months after his emergence onto the pulp fiction

scene, by the editor of

Thrilling Adventures

when he

wrote, “Several of you have wondered, too, how he gets the splendid color which

always characterizes his stories of faraway places. The answer is, he's been

there, brothers. He's been, and seen, and done, and plenty of all three of

them!”

Ron saw over 200 of his fiction stories published

during this time; he wrote in every popular genre, from adventure of every sort

to mystery and thriller, to science fiction and fantasy, to western and even

some romance. He wrote anywhere from 70,000â100,000 words a month, writing only

three days a week, affording him the time he needed for further

adventuring.

Regarding the necessity of devoting oneself to the

task of writing, Ron had this to say:

“If you write insincerely, if you think the lowest

pulp can be written insincerely and still sell, then you're in for trouble

unless your luck is terribly good. And luck rarely strikes twice.”

He featured t

his and

several other topics in instructional essays, which he penned on the business of

writing, addressing concerns common to both the novice and experienced writer

alike. Initially published in such magazines as

Writer's Digest, Writer's

Review, Author & Journalist

and

Writers' Markets

& Methods,

these articles covered topics such as how to get

a story idea, how to create suspense, how to create story vitality and even what

not to tell a writer. These essays would eventually become the backbone of the

now-famous Writers of the Future Workshop as taught by Tim Powers and Dave

Wolverton. The Workshop provides the basic skills of story writing, combining

compassion with encouragement for the fledgling writer, while continuing to

offer insightful lessons in writing techniques.

The first of these instructional essays, written in

late 1935, titled “The Manuscript Factory,” is where Ron brings the sharp,

candid and enlightening insight of a seasoned professional to the practical

rigorsâand rewardsâof writing as a craft and career in an intensely competitive

marketplace.

The Manuscript Factory

S

o you want to be a professional.

Or, if you are a professional, you want to make more money. Whichever it

is, it's certain that you want to advance your present state to something better and

easier and more certain.

Very often I hear gentlemen of the craft referring to writing as the

major “insecure” profession. These gentlemen go upon the assumption that the gods of

chance are responsible and are wholly accountable for anything which might happen to

income, hours or pleasure. In this way, they seek to excuse a laxity in thought and

a feeling of unhappy helplessness which many writers carry forever with them.

But when a man says that, then it is certain that he rarely, if ever,

takes an accounting of himself and his work, that he has but one yardstick. You are

either a writer or you aren't. You either make money or you don't. And all beyond

that rests strictly with the gods.

I assure you that a system built up through centuries of commerce is not

likely to cease its function just because your income seems to depend upon your

imagination. And I assure you that the overworked potence of economics is just as

applicable to this business of writing as it is to shipping hogs.

You are a factory. And if you object to the word, then allow me to

assure you that it is not a brand, but merely a handy designation which implies

nothing of the hack, but which could be given to any classic writer.

Yes, you and I are both factories with the steam hissing and the

chimneys belching and the machinery clanging. We manufacture manuscripts, we sell a

stable product, we are quite respectable in our business. The big names of the field

are nothing more than the name of Standard Oil on gasoline, Ford on a car, or

Browning on a machine gun.

And as factories, we can be shut down, opened, have our production

decreased, change our product, have production increased. We can work full blast and

go broke. We can loaf and make money. Our machinery is the brain and the

fingers.

And it is fully as vital that we know ourselves and our products as it

is for a manufacturer to know his workmen and his plant.

Few of us do. Most of us sail blithely along and blame everything on

chance.

Economics, taken in a small dose, are simple. They have to do with

price, cost, supply, demand and labor.

If you were to open up a soap plant, you would be extremely careful

about it. That soap plant means your income. And you would hire economists to go

over everything with you. If you start writing, ten to one, you merely write and let

everything else slide by the boards. But your writing factory, if anything, is more

vital than your soap factory. Because if you lose your own machinery, you can never

replace itâand you can always buy new rolls, vats and boilers.

The first thing you would do would be to learn the art of making soap.

And so, in writing, you must first learn to write. But we will assume that you

already know how to write. You are more interested in making money from writing.

It does no good to protest that you write for the art of it. Even the

laborer who finds his chief pleasure in his work tries to sell services or products

for the best price he can get. Any economist will tell you that.

You are interested in income. In net income. And “net income” is the

inflow of satisfaction from economic goods, estimated in money, according to

Seligman.

I do not care if you write articles on knitting, children's stories,

snappy stories or gag paragraphs, you can still apply this condensed system and make

money.

When you first started to write, if you were wise, you wrote anything

and everything for everybody and sent it all out. If your quantity was large and

your variety wide, then you probably made three or four sales.

With the field thus narrowed and you had, say, two types of markets to

hammer at, you went ahead and wrote for the two. But you did not forget all the

other branches you had first aspired to. And now and then you ripped off something

out of line and sent it away, and perhaps sold it, and went on with the first two

types regardless.

Take my own situation as an exampleâbecause I know it better than yours.

I started out writing for the pulps, writing the best I knew, writing for every mag

on the stands, slanting as well as I could.

I turned out about a half a million words, making sales from the start

because of heavy quantity. After a dozen stories were sold, I saw that things

weren't quite right. I was working hard and the money was slow.

Now, it so happened that my training had been an engineer's. I leaned

toward solid, clean equations rather than guesses, and so I took the list which you

must have: stories written, type, wordage, where sent, sold or not.

My list was varied. It included air-war, commercial air, western,

western love, detective and adventure.

On the surface, that list said that adventure was my best bet, but when

you've dealt with equations long, you never trust them until you have the final

result assured.

I reduced everything to a common ground. I took stories

written of one type, added up all the wordage and set down the wordage sold. For

instance:

DETECTIVE..............

120,000 words written

30,000 words sold

30,000

----------

= 25%

120,000

ADVENTURE.............

200,000 words written

36,000 words sold

36,000

----------

= 18%

200,000

According to the sale book, adventure was my standby, but one

look at 18 percent versus 25 percent showed me that I had been doing a great deal of

work for nothing. At a cent a word, I was getting $0.0018 for adventure and $0.0025

for detective.

A considerable difference. And so I decided to write detectives more

than adventures.

I discovered from this same list that, whereby I came from the West and

therefore should know my subject, I had still to sell even one western story. I have

written none since.

I also found that air-war and commercial air stories were so low that I

could no longer afford to write them. And that was strange as I held a pilot's

license.

Thus, I was fooled into working my head off for little returns. But

things started to pick up after that and I worked less. Mostly I wrote detective

stories, with an occasional adventure yarn to keep up the interest.

But the raw materials of my plant were beginning to be exhausted. I had

once been a police reporter and I had unconsciously used up all the shelved material

I had.

And things started to go bad again, without my knowing why. Thereupon, I

took out my books, which I had kept accurately and up to dateâas you should do.

Astonishing figures. While detective seemed to be my

mainstay, here was the result.

DETECTIVE.............

95,000 words sold

320,000 words written = 29.65%

ADVENTURE...........

21,500 words sold

30,000 words written = 71.7%

Thus, for every word of detective I wrote I received

$0.002965 and for every adventure word $0.00717. A considerable difference. I

scratched my head in perplexity until I realized about raw materials.

I had walked some geography, had been at it for years and, thus, my

adventure stories were beginning to shine through. Needless to say, I've written few

detective stories since then.

About this time, another factor bobbed up. I seemed to be working very,

very hard and making very, very little money.

But, according to economics, no one has ever found a direct relation

between the value of a product and the quantity of labor it embodies.

A publishing house had just started to pay me a cent a word and I had

been writing for their books a long time. I considered them a mainstay among

mainstays.

Another house had been taking a novelette a month from me. Twenty

thousand words at a time. But most of my work was for the former firm.

Dragging out the accounts, I started to figure up on words written for

this and that, getting percentages.

I discovered that the house which bought my novelettes had an average of

88 percent. Very, very high.

And the house for which I wrote the most was buying 37.6 percent of all

I wrote for them.

Because the novelette market paid a cent and a quarter and the others a

cent, the average pay was: House A, $0.011 for novelettes on every word I wrote for

them. House B, $0.00376 for every word I wrote for

them

.

I no longer worried my head about House B. I worked less and made more.

I worked hard on those novelettes after that and the satisfaction increased.

That was a turning point. Released from drudgery and terrific quantity

and low quality, I began to make money and to climb out of a word grave.

That, you say, is all terribly dull, disgustingly sordid. Writing, you

say, is an art. What are you, you want to know, one of these damned hacks?

No, I'm afraid not. No one gets a keener delight out of running off a

good piece of work. No one takes any more pride in craftsmanship than I do. No one

is trying harder to make every word live and breathe.

But, as I said before, even the laborer who finds his chief pleasure in

his work tries to sell services or products for the best price he can get.

And that price is not word rate. That price is satisfaction received,

measured in money.

You can't go stumbling through darkness and live at this game. Roughly,

here is what you face. There are less than two thousand professional writers in the

United States. Hundreds of thousands are trying to writeâsome say millions.

The competition is keener in the writing business than in any other.

Therefore, when you try to skid by with the gods of chance, you simply fail to make

the grade. It's a brutal selective device. You can beat it if you know your product

and how to handle it. You can beat it on only two counts. One has to do with genius

and the other with economics. There are very few men who sell and live by their

genius only. Therefore, the rest of us have to fall back on a fairly exact

science.

If there were two thousand soap plants in the country and a million soap

plants trying to make money and you were one of the million, what would you do?

Cutting prices, in our analogy, is not possible, nor fruitful in any commerce.

Therefore you would tighten up your plant to make every bar count. You wouldn't

produce a bar if you knew it would be bad. You'd think about such things as

reputation, supply, demand, organization, the plant, type of soap, advertising,

sales department, accounting, profit and loss, quality versus quantity, machinery,

improvements in product, raw materials and labor employed.

And so it is in writing. We're factories working under terrific

competition. We have to produce and sell at low cost and small price.

Labor, according to economics in general, cannot be measured in simple,

homogenous units of time such as labor hours. And laborers differ, tasks differ, in

respect to amount and character of training, degree of skill, intelligence and

capacity to direct one's work.

That for soap making. That also for writing. And you're a factory

whether your stories go to

Saturday Evening Post,

Harper's

or an upstart pulp that pays a quarter of a

cent on publication. We're all on that common level. We must produce to eat and we

must know our production and product down to the ground.

Let us take some of the above-mentioned topics, one by one, and examine

them.

Supply and Demand

Y

ou must know that the supply of

stories is far greater than the demand. Actual figures tell nothing. You have only

to stand by the editor and watch him open the morning mail. Stories by the

truckload.

One market I know well is publishing five stories a month. Five long

novelettes. Dozens come in every week from names which would make you sit up very

straight and be very quiet. And only five are published. And if there's a reject

from there, you'll work a long time before you'll sell it elsewhere.

That editor buys what the magazine needs, buys the best obtainable

stories from the sources she knows to be reliable. She buys impersonally as though

she bought soap. The best bar, the sweetest smell, the maker's name. She pays as

though she paid for soap, just as impersonally, but many times more dollars.

That situation is repeated through all the magazine ranks. Terrific

supply, microscopic demand.

Realize now that every word must be made to count?

Organization and the Plant

D

o you have a factory in which

to work? Silly question, perhaps, but I know of one writer who wastes his energy

like a canary wastes grain just because he has never looked at a house with an eye

to an office. He writes in all manner of odd places. Never considers the time he

squanders by placing himself where he is accessible. His studio is on top of the

garage, he has no light except a feeble electric bulb and yet he has to turn out

seventy thousand a month. His nerves are shattered. He is continually going

elsewhere to work, wasting time and more time.

Whether the wife or the family likes it or not, when the food comes out

of the roller, a writer should have the pick and choice, say what you may. Me? I

often take the living room and let the guests sit in the kitchen.

A writer needs good equipment. Quality of work is surprisingly dependent

upon the typewriter. One lady I know uses a battered, rented machine which went

through the world war, judging by its looks. The ribbon will not reverse. And yet,

when spare money comes in, it goes on anything but a typewriter.

Good paper is more essential than writers will admit. Cheap, unmarked

paper yellows, brands a manuscript as a reject after a few months, tears easily and

creases.