Writers of the Future, Volume 29 (27 page)

Read Writers of the Future, Volume 29 Online

Authors: L. Ron Hubbard

Charlene's father exhaled forcefully, as though he, too, hadn't been

able to breathe for the last few seconds. He tried to nudge her, to turn her around

on his lap, presumably to get a look at her face. She resisted.

She held fastâsuccessfully held!âto her father's leg, not wanting to let

go just yet. She tasted the blood collecting in her mouth, and decided that

bitterness was preferable to letting it drain into her lungs. Maybe the blood and

the monster made the incision look worse than it was. Maybe, if she held on until

the ambulance arrived, she would live long enough to speak to her fathers. She did

feel safe now. Safe from the monster and safe from other whistlers who might be out

there, who would have preferred she speak their language instead of the language of

her fathers.

“Ambulance is on the way,” Daddy Oliver said behind them. And then, just

as urgently: “Do I smell something

burning

?”

Charlene looked up, back at her fort. The laser. She'd forgotten. One of

the pieces of switchboard had the words “fire resistant” printed in small letters

somewhere. She was pretty sure it meant something not as good as “fireproof,” but

that was one of those things she couldn't figure out entirely on her own. She didn't

want to let go, but she had to.

She scrambled off her father's lap. She missed the entrance. She crushed

the fort with her body. The collapsing switchboard made it impossible for her to

reach in and shut off the laser, but her attempt was enough to get Daddy Oliver to

see the light.

“What the hell?”

He reached in, found the component and switched off the laser.

“This some kind of sick toy?”

“I've never seen it before.”

“Think it's that thing my sister got her.”

“Yeah? Well, I told you it was inappropriate.”

Charlene coughed up another spurt of blood. She scrambled back into

Daddy Gary's lap. Less than twenty seconds, but only because both fathers

helped.

She knew her throat would take days to heal. Everything would still take

days, at least. Even then,

if

she could avoid infection

and

if

she hadn't cut too much out of her throat, there

was still no guarantee she'd ever be able to move or speak like a normal person. But

she gave the latter a try anyway. She knew exactly what to do. She'd studied and

planned for this moment longer than for any other.

Tentatively pushing air out through her tender and scarred vocal folds,

Charlene tried vibrating them until it sounded less like wind and more like a human

groan. She pushed more forcefully and eventually got a sound like an “Ah.”

“Buddy?”

As her fathers waited for the ambulance, they stared, one leaning over

the other's shoulder, both half crying and half gaping at their daughter's ability

to make a nonwhistling sound. Daddy Oliver wrapped a blanket around Charlene, and

she welcomed the extra touch, though she was sweating and unsure of whether she was

hot or cold. Both, maybe. The uncertainty about herself and her future was

exhilarating.

Charlene next tried blocking the airflow through her mouth. She waited

until her fidgeting tongue rested momentarily against her front upper teeth. Then,

eventually, she managed to force the tongue to snap down as she made the “ah” sound

again. Twelve seconds, maybe? The result, she hoped, would sound like “DA.”

“Jesus. Did you hear her?”

“Yeah, she was totally talking to

me

.”

“You wish.”

Charlene wanted to smile. Maybe that would be her next project. Right

now she would have to start over, to say “DA” a second time for her second father.

But they were worth the challenge, and generating human speech wasn't nearly as

complex as she'd worried it would be.

As Charlene waited for her tongue to find its position again, she

wondered whether she would miss her whistling ability, the one thing she was

actually good at. And if she was right about other whistlers being out there? How

would she speak to them?

Her tongue rested again against her upper teeth. She prepared to snap it

down. If there were indeed other whistlers, and they were indeed smarter than her

fathers and other “regular” people, why should

Charlene

be the one to have to figure out how to communicate with

them

?

She could do anything she wanted now. She wasn't her fathers' monster

anymore. She could even stop crying, if she wanted to.

Holy Days

written by

Kodiak Julian

illustrated by

ALDO KATAYANAGI

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Kodiak Astrid Julian spent her childhood in

museums, forests and libraries. With her siblings and friends, she created

stories about numerous imaginary worlds. Many of these stemmed from “what if”

questions: What if people could turn into animals? What if back rooms of

buildings went on forever? What if a card game could make wishes come true? Her

curiosity led her to study in Japan and at Reed College, where she earned a

degree in English.

Kodiak now lives in rural Washington State with her

husband and young son. She works as an instructional coach, helping public

school teachers implement educational research in their classrooms. Her writing

often explores the relationship between the mundane and the cosmic. She is

currently working on a novel, reimagining Arthurian legends as a contemporary

apocalyptic Western. “Holy Days” is her first published fiction.

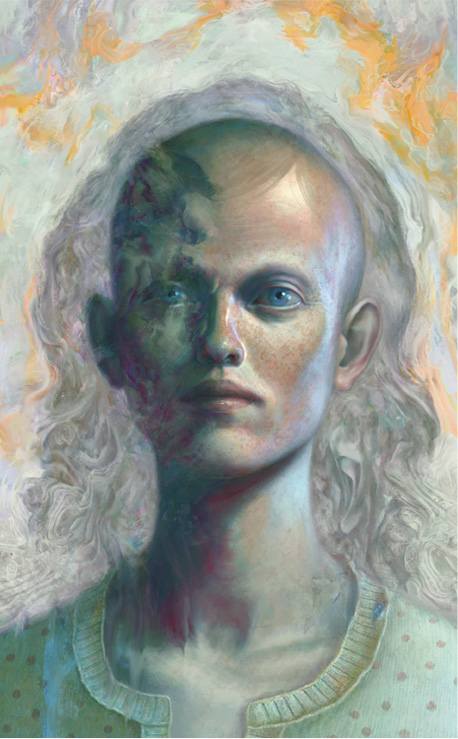

ABOUT THE ILLUSTRATOR

Born to two creative professionals, Aldo

Katayanagi was encouraged from a young age to study medicine. At age five he

watched an anime called

Akira,

and it affected him

greatly. Aldo didn't consider the possibility of a career in art until he

stumbled across various online art forums near the end of high school. He then

rediscovered his love for sci-fi and comics and moved to New York to attend the

School of Visual Arts, where he graduated. Aldo is at peace with his decision to

study art instead of medicine.

Though Aldo is primarily a digital artist, his time

spent oil painting in college was an invaluable experience and still influences

the techniques he uses today.

Aldo currently lives in Chicago, where his art often

combines lighthearted and disconcerting elements that play off and redefine one

another. His work has been exhibited at the Society of Illustrators.

You can visit his website at

aldo-art.com

.

Holy Days

1. Break Day

E

ven though I had been looking forward to Break Day, I woke to panic. The pregnancy books had told me it was normal. I knew that the baby would return at midnight and that no one ever went into labor before the baby came back. But I was almost nine months along. Stuffed as I was, with her elbowing me in my lungs and heart, I'd grown accustomed to only one state of life, and that was with her squirming inside me.

I put on the shorts that I had been saving for Break Day and went into the kitchen where James was cooking. “Morning, Evie,” he said, slipping an egg into hot water. “Look at you!” He grabbed me around the waist and pulled me in for a hug. “You're so little!” he said. “I forgot you were so little.”

I traced the space between the cool kitchen tiles with my toes. The giddy July light sliced between the leaves of our oak tree and through the window, making bright knives on the floor. “I'm lonely,” I said.

James squeezed again. He had the salt and blood smell of sleep, and his hair was the oily mess it becomes after a few hours without a shower. I knew that he had awakened early and gone straight to the kitchen for my sake. “Real coffee this morning,” he said. “And eggs Benedict. Little bit of raw, runny eggs before you go back to being careful.”

“Maybe you should put a shot of whiskey in the hollandaise.”

“Mmm,” said James. “Or a slab of sushi. Some kind with extra mercury.” He scooped the egg from the pot and slid it onto an English muffin half.

I stood behind him and put my arms around his waist, locking my legs around his. He tried to cross the kitchen but floundered.

“Hey, Ball-'n'-Chain,” he said. “I'm trying to make breakfast. You okay?”

“No.”

James turned around. “Why are you crying?”

“I'm lonely,” I said again.

“Damn,” he said. He kissed me, and then he kissed me again. “Me, too.”

After breakfast, I wrestled with the garden weeds. It wasn't my first choice of how to spend the day, but they weren't going to uproot themselves. If I was going to squeeze a baby into the sunlight, then I'd better have real garden tomatoes as my reward. Over the last few weeks, when my belly got in the way of gardening, the tangle of green had thickened and curled. The largest of the tomatoes had just begun to change color. A few dangled near the ground as though exhausted. One had already grown so full that its seams split. I rebalanced the fruits within their wire cages, hoping that they would be safe from slugs and rot for another month.

In midmorning, my sister, Rosie, and her husband, Scott, rode their bikes to our house. It was startling to see her, just as it had been on the other Break Days over the last two years. She had what Mom called the angel glow, a look that I never managed to cultivate even in pregnancy. I hoped it was from sex, but it might have been from the bike ride. Perhaps she had always been radiant, and I simply didn't notice in the days when it was normal for her. Chemotherapy had taken most of her eyebrows, and she had taken to drawing them on with liquid eyeliner, angry arches that she called her bitch eyebrows. “Angry patients live longer,” she told me. “If I forget to be angry, my eyebrows might do it for me.” Just for today, her hair was back, and she looked softer, more round and whole and gentle.

ILLUSTRATION BY ALDO KATAYANAGI

Scott and James stayed in the driveway to get in a game of basketball without their usual bad knees and arthritic hands. Rosie and I packed a bag with bathing suits and towels and took a walk down to the park. Top 40 music bounced from houses, and small groups of people hiked up and down the street, chatting with each other and grinning. All the strangers looked at us as though we all knew each other, as though we were all in on the same secret together. And we were. As we walked down the hill, a rivulet of water from garden hoses flowed in the gutter. Rosie walked in the stream, getting her sandals and feet wet.

“It always amazes me how many people want to wash their cars on Break Day,” said Rosie. “Is that fun? Is there something great about washing metal that I just didn't get in the life manual?”

“If there is, then I missed it, too,” I said. I swung my arms. “I feel so light.”

“Well, you just lost, what, thirty pounds?”

“Ugh,” I said. “Don't tell anyone, but it's more like thirty-five and I'm hoping to keep it under forty.”

“That's not bad,” said Rosie. “Or so I hear.”

The tree canopy of the park made the midday heat bearable. Crowds were already gathering at the picnic tables, laying out potato salad and cupcakes. Old men had taken over the park's grills, their walkers left behind at nursing homes. Their white-haired friends stood near them, ancient men who only came outside on this one day a year. They stood without the hunches in their backs, punching each other in the arms like college students.

“I love the smell of lighter fluid and charcoal,” Rosie said.

“Why didn't we ever come here when we were growing up?” I asked.

Rosie made a snorty little laugh. “Can you imagine Dad wanting anyone to know that there was something wrong?”

“People could have imagined that someone in our family had migraines,” I said. “Or insomnia. Or maybe we were there to support everyone else.”

“Please,” said Rosie. “If you even had a thought about illness, Dad would take it personally.”

We'd never talked about Break Day when we were kids. It wasn't the only day in the year when Dad was sober. He sobered up on other days, too, but this was a day when he got sober without having to work at it. Some years we'd gone on a hike in the mountains. On rainy days, we'd all stayed home to play Monopoly and eat popcorn. Just the four of us together and nobody daring to mention that anything was out of the ordinary.

Rosie led the way to the picnic area where feasts were spread on top of bright tablecloths. Someone had laid out their good china and assembled huge bouquets of roses.

“Cancer support?” Rosie asked a middle-aged woman wearing sparkles on her eyelids.

“Yes!” said Sparkle. “And don't you look beautiful today!”

“You, too!” said Rosie, and Sparkle beamed. “This is my sister,” Rosie said. “She's going to have a baby next month.”

Sparkle looked at my strange little body and laughed. Loneliness struck again like a chime.

“Eat, eat!” Sparkle said.

We filled plates with chocolate-covered strawberries, watermelon spears, deviled eggs, Brie, crusty bread, homemade pickles, cupcakes with frosting fluted to make tiny lavender flowers. Someone had rigged up a sound system, and as we ate, Sam Cooke sang about love.

Afterward, we went to the swimming pool at the other side of the park. Scott and James joined us. The guys and Rosie just wanted to splash each other, and Rosie kept dunking Scott. I pulled myself from the water and sunned on a towel. There were a few groups of kids splashing around. Some of them looked like siblings. Which kids were the sick ones? Which kids would be dead in a year?

I fell asleep on my towel and imagined us all holding hands, our heads bobbing just above water. I woke to the sound of Rosie standing over me and laughing.

“I'm done with fighting,” she said, “so what now?”

“I have to get out of here,” I said. “I have to get things done. What if the baby is supposed to be coming right now? What if I'm suddenly in labor at midnight? Or what if I miss the whole thing?”

James knelt beside me. Little beads of water clung to his beard. “That isn't going to happen,” he said.

“How do you know?”

“Because I know.”

“Because you know in the way that means you're making it up?”

“What do you want to do?” James said. “Is there anything left that you still want to do?”

2. Homecoming Day

I

gave birth to Anna, but my body did not return to me. When James was home, I called him from across the house: bring me bottles of water, a pillow, a book, an apple, a cardigan. I could do nothing but feed Anna's red and hungry mouth.

I stood with her in the yard, the crunch of morning air soothing her cries. “See how the leaves become golden,” I told her. “Look at the big, round pumpkins.” On the good days, I walked her in the stroller until she slept, then hurried her home so that I could collapse. On the bad days, Anna would not sleep unless her mouth was full. She and I took naps together in the big bed, her still sucking, my arms at painful angles. When I could not sleep, I watched her strange light. She was so freshly drawn from the deep well between the worlds, a tiny goddess in my arms. I would not let her feet touch the ground.

When had I last slept for more than an hour at a time? When had I last felt strong? I was a ragged traveler at Anna's shrine, kneeling and praying, bruised and starved. I would carry water for her. I would lay wreaths of flowers around her neck.

Was it Homecoming Day, or was I dreaming again, dreaming while still listening to Anna's cries? I knelt in the house where I grew up, on the family room floor, tracing a Matchbox car over the orange and brown carpet squares. Beside me, Rosie had built a tower of blocks, humming the theme song from

The Smurfs

. She smelled like peanut butter and Cheerios.

“Tell me about your castle,” said Mom. She sat beside us, old and young at once, wearing the sweater I had forgotten about, the one with the big silver buttons.

“It's a cathedral,” Rosie said. “The lions are going there to get married.”

Monster shadows seethed on the walls. “Why are you crying, Mama?” I asked.

“It's a special day,” Mom said. She made us tuna casserole and green beans for dinner. She let us eat off of our special bunny plates. When we asked, she said that Dad would be home soon. But then he wasn't home. “Soon,” Mom said.

Rosie and I splashed our boats in the bathtub, and Mom piled bubbles into crowns for our heads. “Why do you cry and smile at the same time?” Rosie asked.

“It's something grownups do,” said Mom.

She dried us, tucked us into our bed, and there was the smell of clean Rosie. Mom read to us from

A Child's Garden of Verses

. Later, I lay in the dark, watching the maple tree shiver against the window.

In the half slit of my eyes, I was on the living room couch with Anna, her head tucked into my armpit. I craned my neck forward into the long hallway of her life to come: favorite teachers and bad roommates, piano lessons, mopping with pine soap, her own child on her lap as they read about zoo animals, willing herself to rise from the driver's seat and begin working the night shift, the shock of unexpected obituaries, the first tomatoes of summer, knocking down spider webs with a broom. Was she with me now because she really was a baby, or was she with me because it was Homecoming Day? Was she three months old, or had time passed? Was she thirty-five years old, here to bring me yet another chance to hold her and rock her? Was she older? And how old was I? Was I at the end? Was there really any moment besides this quiet, frozen instant: a tired mother, a warm child, a breast to suck, the brink of sleep?

3. Secret Day

T

he air froze and went silent. Each day James left in the dark and returned home in the dark. Several times a week he woke during the night to give Anna a bottle so I could sleep. In the moments when my hands were free, I dismantled the contents of our pantry, putting everything into the slow cooker: cans of tomatoes and beans, barbecue sauce, marinara sauce, onions, potatoes, artichoke hearts, cream of mushroom soup, chicken noodle soup, pineapples. We ate our horrible dinners in front of the television. We piled laundry like haystacks throughout the house. I filled garbage bags with Anna's baby chick pajamas, with her little lamb pajamas, with her turtle pajamas, the heartbreaks of tiny clothes that she would never wear again. Somehow we needed to find time to take them to the Goodwill. But where was time?

My body had healed, but James and I did not touch.

Anna learned to laugh, and I spent my days trying to draw the laughter from her, blowing up my cheeks and making the noises of geese. I brought her spoons and spatulas, and she lay on her stomach, thunking her toys against the wood floor.

When Secret Day came, I thought about staying home, but the day was made of melting snow and a fussy wind. The yard was full of mud. Staying home wouldn't make the day any less itchy.

I wrestled Anna into her car seat, tossed a bag of toys beside her and drove to a coffee shop. I fought the wind to open car doors, and made the wet walk across the parking lot. Inside the shop, customers spoke in hushed pairs, glancing at the door. They were probably just as nervous as I was.

On Secret Day, I never knew what was going to show. Rosie said that she liked it, because she got to see how she wasn't alone. She had called me last year, announcing that she had just been to the grocery store.