Writing and Selling the YA Novel (6 page)

Read Writing and Selling the YA Novel Online

Authors: K L Going

Realistic questions aren't the only ones that can spark ideas. A different type of question you might use is the "What if " question. Start a question with "What if" and then fill in the blank. For example, you might ask yourself, "What if I was the child of an immigrant family?" or "What if the world entered a new ice age?" or "What if we could travel back in time?" While this technique works well for realistic situations, it's also great for generating ideas outside the familiar realm. I especially recommend it if you're searching for teen fantasy or science fiction ideas. By asking ourselves "What if" questions, we can twist reality until it becomes unrecognizable.

If you like a particular question and its answer, be sure to follow it through until you run out of questions. For example, you might start with a question like this: What if I lived on a planet almost exactly like this one, only in a different galaxy? Then you could add: What if my family was one of the first to colonize this planet and we did so just before a nuclear holocaust on Earth, so now we are forgotten? Continue on to: What if there were no other teenagers and I couldn't stand my parents?

Let each question spark the next question. You might even combine questioning techniques so you can see a story from every angle. Maybe the teen who hates his family is somehow different from them, so although others in the group tolerate him, he's not taken seriously

in this harsh environment. Ask yourself what it might be like to be different. How would he prove himself to others? What kind of a struggle might he and his family have gone through in order to make it to the planet in the first place? How did the teen feel about leaving Earth? Now that they're stranded, does he feel vindicated or foolish? How does he handle his emotions?

By starting with a "What if" question, you can arrive at an idea that might lead you to a character. What began as a scenario has now reached the point where human emotions are involved, and those emotions will lead to actions that will define the person in your mind. Now he's no longer a teenage placeholder, he's a boy with intense struggles who must deal with extreme isolation. As you ask yourself

how

he does this, and

why

he does this, your answers will shape his character until soon, he just might become unforgettable.

MEMORIES

When an idea sticks in your mind, there's usually a reason. W.H. Auden said, "Some books are undeservedly forgotten; none are undeservedly remembered." The same could be said for people, places, and events. Don't be afraid to delve into your own memories or let the memoirs of others inspire you. Many writers get hung up on the idea that every facet of a story must come from their own imaginations, but every one of us draws from real life all the time. I find biographies to be excellent idea generators, and the details they reveal about a particular time and place can be helpful in creating a setting.

Interviews are also excellent ways of learning about the past or finding out key information. Ask people questions about their past and present. Maybe your neighbor was one of those first "teenagers" we learned about in Homeroom. Find out what it was like to live

through "World War II, then let those memories suggest possible story ideas. Even if you don't end up using the actual events the person describes in a book, you might get an idea based on the emotions involved. Hearing the true account of someone's first love or last goodbye might spark a novel full of romance or pathos. Just be sure to make the story your own.

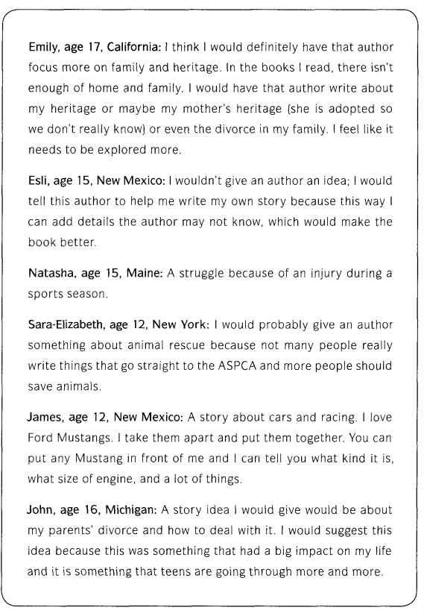

Interviews aren't relegated to the elderly, either! Try interviewing teens. Ask them about their lives. What kind of school do they go to? What are their daily struggles? What do they want to be when they grow up? What kind of books do they like to read? Or you could interview school principals. What do they see happening in the halls from day to day? Which kids break their hearts and which ones drive them crazy?

Questions work so well as idea-generatingtools in part because they allow us to reach out to the world around us. Whether that takes the form of imagination, empathy, or fact gathering, when we're asking questions we're engaged with reality—what it is, what we wish it were, and what it could be. Engaging in the world is essential for any writer. The more you notice and experience, the more extensive your palette of ideas.

By now your brain should be wide awake, ready for action. It's time for the real workout to begin. Anyone can warm up, but only true athletes run the race to the finish line. "What's the finish line for a writer? It's moving from having many potential story ideas to choosing

one

and turning it into a book. Can you reach the finish line with your writing? Absolutely. The first step is choosing the best idea to pursue.

So, how do you find the one idea you want to write your book about? This process is twofold. You not only have to find the idea that works best for you; it also has to be the right time for that idea. Sometimes, an idea that seems only so-so at the present might come back strong a year or two later. Perhaps events in your own life might shift in a way that makes a story about loss or pain or joy suddenly more compelling. I know many authors who keep idea files for just this reason. They jot down their story ideas on index cards and then store them away. This way they can go back to an old idea at any time; an idea is never lost.

Personally, I let my subconscious do the sifting for me. When an idea is compelling enough that it won't leave me alone—when I come back to it again and again and again—that's a story I'll pursue. Some ideas might stick around for years before I'm ready to write them. Others force their way forward fairly quickly.

The "sticky" factor is extremely important in determining which idea to turn into a novel. Writing a book can take months or even years, so it's important that the idea you choose can hold your interest for that amount of time. It needs to be something you deeply care about rather than something that seems good at the moment.

A large part of this "stickiness" will be how you feel about your main character. We'll talk more about characters next period, but for now I'd like to mention that idea generating is not just about coming up with plots. This is a common misconception among beginning writers who equate a fabulous idea with the next great plot device. In reality, ideas can come in the form of characters as well as plots, and it's often the characters who are the most apt to grab us and not let go.

One thing I learned during my time in publishing is that no matter how unique you think your idea is, chances are someone else has thought of a similar plot. I asked my editor about this when, just before

Fat Kid Rules the World

was to be published, another editor sent us a link to an Australian book called

Fat Boy Saves World

, by Ian Bone. I was shocked. How was it possible someone else had come up with a title so similar to my own? I panicked, but my editor did not. She told me that when a story comes from the heart, the way an author writes it and the characters she creates are what will make the book unique. I've kept this in mind ever since, focusing on characters and my own emotional involvement rather than depending on a clever plot device when choosing which ideas to pursue.

You also need to choose ideas that have meaning and relevance for you rather than ideas you perceive as marketable. Just as our perception of originality can be shattered by someone unexpectedly publishing a book with a similar title or plot, our perceptions of marketability can also change in an instant. Before the first

Harry Potter

was published, fantasy was waning, but afterwards it has seen an unprecedented surge in sales.

This is great for aspiring fantasy writers, right? Maybe you have only a marginal interest in fantasy but think you could produce a solid submission while the market is ripe. Unfortunately, you're not the only one who thinks this. Whenever a book in a given genre makes it big, there's always a corresponding surge in people wanting to write and submit similar books. So, although the market has increased, so has your competition.

Many aspiring authors don't realize how long the publishing process takes, and they assume they'll have time to write and submit a book before the market changes again. In reality, even if you are a very fast writer, the submission process can take many months or even years. If you've based your book on an idea of what will sell, chances are that will have changed by the time your novel is being considered by editors.

It's been said many times before, but it's worth saying again:

Write what you love!

When choosing an idea to pursue, banish all thoughts of marketability and focus on where you can invest the biggest piece of your soul. Which idea has personal relevance for you, and which idea do you think will have the most relevance to your teen readers? Which book would you write even if I told you right now that it would never sell to a publishing house?

That's the idea to choose.

ARTICLES VS. NOVELS

_

Hopefully, by now you're ready to cool down. This is the time to stand back, breathe deeply, and take one more hard look at the idea you've chosen. I believe passion should be foremost in your mind right now, but there are some practical considerations as well.

When I worked at Curtis Brown, Ltd., we often submitted nonaction proposals to editors. One of the most common reasons editors gave for rejecting a proposal was the phrase, "This is an article, not a book." In other words, it's a catchy idea, but no one's going to want to read two or three hundred pages of it. Whether you're writing fiction or nonaction, the "article test" is a good one to apply. Ask yourself what kind of depth an idea can inspire. What level of conflict is present? What might a character need to learn from beginning to end and which obstacles might she have to overcome? Is there enough substance to sustain a whole book?

It might be helpful at this point to determine what your motivation is for wanting to pursue a given idea. Are you driven by a true desire to tell the story or do you see the story as a vehicle to make a point? When it comes to books for teens, writers often want to teach or guide, and there's nothing wrong with that as long as the story comes first. Otherwise, you'll most likely find that your idea fizzles midway through. Could you read a two hundred-page lecture? Probably not, and neither will the average teen. If your motivation is primarily to instruct, perhaps there's another venue better suited to what you have to say.

In fact, choosing the right venue for an idea is as essential as coming up with a good idea in the first place. Certain ideas will, naturally, be better suited to certain styles of writing. I'll give you an example from my own experience.

One afternoon, my husband was relating a story about an event that happened in an NFL football Xbox game he'd been playing with a friend. He told me about the event as if it had been real, and it was only because of my prior knowledge of the game's existence that I knew he and his friend had not actually made the play he was telling me about. This sparked a "What if " question: What if in the future games become so common and so advanced that people cease to do anything real but still feel as if they have accomplished great things?

Based on this question, I extrapolated a scene where a group of teens discuss their accomplishments. Only at the end of the conversation would the reader realize the characters had never left their own living rooms. Their "great deeds" had, in fact, all taken place in virtual reality.

At first this idea seemed novel-worthy, but as I began to think about it, I wondered if it would really carry through for several hundred pages. Would I be able to maintain the illusion so the ending could be a surprise? How would my action and character development be limited because of my plot device? Was there a single character I could develop in a compelling way? How would that character change from beginning to end if the success of the story was dependent on the reader's discovery that the character had, in fact, been doing nothing?