XSLT 2.0 and XPath 2.0 Programmer's Reference, 4th Edition (739 page)

Read XSLT 2.0 and XPath 2.0 Programmer's Reference, 4th Edition Online

Authors: Michael Kay

select=“$possible-moves[1]”/>

select=“$possible-moves[position() gt 1]”/>

select=“tour:place-knight(99, $board, $trial-move)”/>

select=“tour:list-possible-moves($trial-board, $trial-move)”/>

select=“count($trial-move-exit-list)”/>

select=“min(($number-of-exits, $fewest-exits))”/>

select=“if ($number-of-exits lt $fewest-exits)

then $trial-move

else $best-so-far”/>

select=“if (exists($other-possible-moves))

then tour:find-best-move($board, $other-possible-moves,

$minimum-exits, $new-best-so-far)

else $new-best-so-far”/>

And that's it.

Running the Stylesheet

To run the stylesheet, download it from

wrox.com

and execute it. No source document is needed. With Saxon, for example, try:

java -jar saxon9.jar -it:main -xsl:tour.xsl start=b6 >tour.html

The command line syntax shown here applies to Saxon 9.0 or later. However, if you want to run the stylesheet with an earlier version of Saxon you can do this simply by adapting the way the command line options are written.

The output of the stylesheet is written to the file

tour.html

, which you can then display in your browser.

Using the Altova XSLT 2.0 processor, the equivalent command line is:

altovaXML -xslt2 tour.xsl -in tour.xsl -out tour.html -param start=‘b6’

(At the time of writing, Altova does not provide any way of nominating an initial template as the entry point, so it is necessary to supply a dummy input document. The stylesheet is as good as any other.)

Observations

The knight's tour not a typical stylesheet, but it illustrates the computational power of the XSLT language, and in particular the essential part that recursion plays in any stylesheet that needs to do any non-trivial calculation or handle non-trivial data structures. And although you will probably never need to use XSLT to solve chess problems, you may just find yourself doing complex calculations to work out where best to place a set of images on a page, or how many columns to use to display a list of telephone numbers, or which of today's news stories should be featured most prominently given your knowledge of the user's preferences.

So if you're wondering why I selected this example, there are two answers: firstly, I enjoyed writing it, and secondly, I hope it persuaded you that there are no algorithms too complex to be written in XSLT.

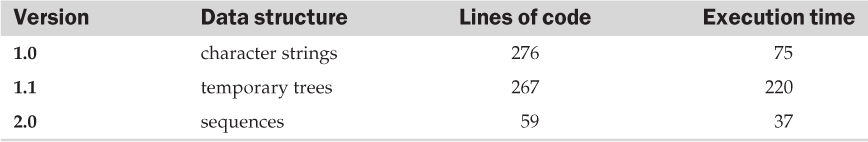

The other thing that's worth noting about this stylesheet is how much it benefits from the new features in XSLT 2.0. In the first edition of this book, I published a version of this stylesheet that was written in pure XSLT 1.0; it used formatted character strings to represent all the data structures. In the second edition, I published a revised version that used temporary trees (as promised in the later-abandoned XSLT 1.1 specification) to hold the data structures. The following table shows the size of these three versions (in non-comment lines of code), revealing the extent to which the new language features contribute to making the stylesheet easier to write and easier to read. The table also shows the execution times in milliseconds of each version, using Saxon 9.0, which reveals that the XSLT 2.0 solution is also the fastest:

In the previous edition of the book, the numbers reported in the last column (for Saxon 7.8 on a slower machine) were 580 ms, 1050 ms, and 900 ms, respectively. Repeating the measurements on my current machine with Saxon 7.8 gives figures of 180 ms, 360 ms, and 340 ms. At that stage in the development of Saxon, the native 2.0 constructs were significantly slower than the traditional XSLT 1.0 way of doing things. The position is now reversed—instead of being half the speed, the 2.0 solution is now twice as fast as the 1.0 code.

The earlier versions of the stylesheet are included in the download file under the names

tour10.xsl

and

tour11.xsl

. The file

ms-tour11.xsl

is a variant of

tour11.xsl

designed to work with Microsoft's MSXML3 and later processors.

Summary

If you haven't used functional programming languages before, then I hope that this chapter opened your eyes to a different way of programming. It's an extreme example of how XSLT can be used as a completely general-purpose language; but I don't think it's an unrealistic example, because I see an increasing number of cases where XSLT is being used for general-purpose programming tasks. The thing that characterizes XSLT applications is that their inputs and outputs are XML documents, but there should be no limits on the processing that can be carried out to transform the input to the output, and I hope this example convinces you that there are none.

In these last three chapters, I've presented three complete stylesheets, or collections of stylesheets, all similar in complexity to many of those you will have to write for real applications. I tried to choose three that were very different in character, reflecting three of the design patterns introduced in Chapter 17, namely:

- A rule-based stylesheet for converting a document containing semantic markup into HTML. In this stylesheet, most of the logic was concerned with generating the right HTML display style for each XML element, and with establishing tables of contents, section numbering, and internal hyperlinks, with some interesting logic for laying data out in a table.

- A navigational stylesheet for presenting selected information from a hierarchical data structure. This stylesheet was primarily concerned with following links with the XML data structure, and it was able to use the full power of XPath expression to achieve this. This stylesheet also gave us the opportunity to explore some of the systems issues surrounding XSLT: when and where to do the XML-to-HTML conversion, and how to handle data in non-XML legacy formats.

- A computational stylesheet for calculating the result of a moderately complex algorithm. This stylesheet demonstrated that even quite complex algorithms are quite possible to code in XSLT once you have mastered recursion. Such algorithms are much easier to implement in XSLT 2.0 than in XSLT 1.0, because of the ability to use sequences and temporary trees to hold working data.

Part IV

Appendices

Appendix A:

XPath 2.0 Syntax Summary

Appendix B:

Error Code

Appendix C:

Backward Compatiblity

Appendix D:

Microsoft XSLT Processors

Appendix E:

JAXP: The API for Transformation

Appendix F:

Saxon

Appendix G:

Altova

Appendix H:

Glossary

Appendix A

XPath 2.0 Syntax Summary

This appendix summarizes the entire XPath 2.0 grammar. The tables in this appendix also act as an index: they identify the page where each construct is defined.

The way that the XPath grammar is presented in the W3C specification is influenced by the need to support the much richer grammar of XQuery. In this book, I have tried to avoid these complications.

The grammar is presented here for the benefit of users, not for implementors writing a parser (the W3C spec adopted the same approach in its final drafts). So there is no attempt to write the syntax rules in such a way that expressions can be parsed without lookahead or backtracking.

An interesting feature of the XPath grammar is that there are no reserved words. Words that have a special meaning in the language, because they are used as keywords ( if

if ,

, for

for ), as operators (

), as operators ( and

and ,

, except

except ), or as function names (

), or as function names ( not

not ,

, count

count ) can also be used as the name of an element in a path expression. This means that the interpretation of a name depends on its context. The language uses several techniques to distinguish different roles for the same name:

) can also be used as the name of an element in a path expression. This means that the interpretation of a name depends on its context. The language uses several techniques to distinguish different roles for the same name:

- Operators such as

and

and are distinguished from names used as element names or function names in a path expression by virtue of the token that precedes the name. In essence, if a word follows a token that marks the end of an expression, then the word must be an operator; otherwise, it must be some other kind of name.

are distinguished from names used as element names or function names in a path expression by virtue of the token that precedes the name. In essence, if a word follows a token that marks the end of an expression, then the word must be an operator; otherwise, it must be some other kind of name. - As an exception to the first rule, if a name follows

/

/ , it is taken as an element name, not as an operator. To write

, it is taken as an element name, not as an operator. To write /

/

union

/* , if you want the keyword treated as an operator, you must write the first operand in parentheses:

, if you want the keyword treated as an operator, you must write the first operand in parentheses: (/)

(/)

union

/* . Alternatively, write

. Alternatively, write /. union /*

/. union /* .

. - Some operators such as

instance of

instance of use a pair of keywords. This technique was adopted in XQuery for use at the start of a construct such as

use a pair of keywords. This technique was adopted in XQuery for use at the start of a construct such as declare function

declare function , but it's not actually needed for infix operators.

, but it's not actually needed for infix operators.