You Have No Idea: A Famous Daughter, Her No-Nonsense Mother, and How They Survived Pageants, Hollywood, Love, Loss (10 page)

Authors: Vanessa Williams,Helen Williams

I’ve always had “my List.” Ness will say I remember every negative comment that’s ever been said by friends, acquaintances, the media. I’d like to say I can forgive. But I can never forget. It’s just not my nature. I can’t do it. Maybe that means I’m not really forgiving anyone, either.

I think of the List more as my being somewhat of a mama bear protecting her cubs. Before Vanessa became Miss America, the List was manageable. Then the scandal broke out and the List took on a life of its own. I would constantly say, “That person’s on my List.”

Here’s a sampling.

MY LIST

JOAN RIVERS

.

I know her shtick can be cutting and sarcastic. But she was downright cruel to Vanessa, and she made me furious. I fumed and glared at the television. I accepted that she is a comedian and jokes would be told, but I still thought there would be a bit of sensitivity in her comments because she is also the mother of a daughter. It was naive of me, but the jokes did hurt.

TONY BROWN.

I couldn’t stand him. I loathed him. He had a local radio show and is the host of PBS’s

Tony Brown’s Journal.

He’s supposed to be this “civil rights crusader”—but to me, he isn’t at all. He’s a mean-spirited, hypocritical person with a cable show. It seemed to me that he had a big problem with my light-skinned black daughter. Vanessa was a target of his hate from the beginning. Then when the pictures came out, he spent weeks and weeks just destroying her, calling her names. I stopped listening. He’s probably a contributing factor to why I have high blood pressure.

THE PAGEANT PEOPLE.

It really infuriated me that Vanessa was Miss America for nearly eleven months and when the scandal broke, pageant officials had her chaperone drop her off at the front door, and we never heard from anyone again. It was like they couldn’t get rid of her fast enough. They just wiped their hands of her because they felt she was no longer of any value to them. I was optimistic for a while. I really thought they would call or make some contact. When they didn’t, I had no choice but to put them on the List.

THE WOMEN OF

THE VIEW

.

A few years ago Vanessa produced and starred in a TV movie,

The Courage to Love.

She

played a nun.

The View

discussion centered on questioning Vanessa’s producing and starring in a story about a nun after what she did. As her mom I went into protective mode. So I wrote a letter to the show expressing my feelings about what I perceived to be an unfair criticism. The response I received was the standard acknowledgment postcard—but I felt better.

My first apartment on the eastside. Moving on up!

PART TWO

THE

RIGHT STUFF

CHAPTER

5

I

was twenty-three and scared when I found out I was pregnant. I didn’t think I had a maternal instinct in my body. I had never babysat or changed a diaper. I’d never even been around little children. When it came to motherhood, I didn’t have a role model to imitate. I wasn’t sure if I would be able to be a good mother.

But Milton assured me I’d be a natural. He’d grown up around children of all ages. He knew how to change diapers, fix a bottle, and put a baby to sleep. It would be easy, he promised.

I had my doubts.

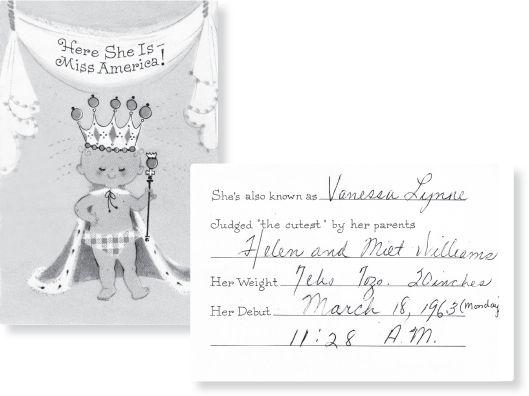

Vanessa was born ten days late on March 18, 1963, at 11:28

A.M

., weighing seven pounds seven ounces, and measuring twenty inches. She was beautiful, with brown hair and smoky blue eyes. We named her Vanessa Lynne for two reasons:

Vanessa

is an opera by Samuel Barber, one of my favorite composers; and Vanessa means

butterfly

in Greek. I have always loved butterflies—they’re so graceful and they come in such a wonderful assortment of colors. (I may get a butterfly tattoo one of these days.)

I was lucky—Vanessa was a happy and healthy baby. She’d been easy before she was born—I didn’t have morning sickness or strange cravings. When I was in labor, I only had some lower back pain—and I was only in labor for about two hours.

But she let out this fierce cry when she was hungry or wet or wanted something that we couldn’t figure out. Once she got going, she was almost impossible to stop. Even as a baby she wanted everyone to notice her. I discovered that if I set her in her playpen in the middle of a room of people, she’d quiet down. She loved to be around people.

One time a reporter said, “Tell me something about Vanessa that no one knows.” So I said, “Well, she used to suck her thumb.” He wanted some dirt, but that’s what I gave him. She was a thumb sucker; and we couldn’t get her to stop. I sewed little mitts and put them on her hand, but she’d just pull each of them off and get at that thumb. I dipped her finger in a bitter solution, but she didn’t mind the taste—she just wanted to get at that thumb. Finally, when it was time to go to preschool, she stopped.

Here’s another thing no one knows about Vanessa: As a baby she’d wail whenever the theme song from

Lassie

came on the television. Milton and I couldn’t figure it out. We’d look at each other and ask, “What is bothering her so much?” Was she afraid of the big dog? Or did the music make her very sad?

Even then, there were some things about Vanessa that we just couldn’t figure out.

CHAPTER

6

If you’re going to run away from home, that’s fine—just make sure you don’t cross the street when you do!

—HELEN WILLIAMS

W

hen I close my eyes and think about my childhood, I can hear its sound track:

Mom’s downstairs in the family room at the baby grand piano, ordering students to play their scales. While my dad—a one-man woodwind and brass ensemble—is upstairs teaching trumpet or clarinet or saxophone or French horn or oboe to a neighborhood kid. In between lessons, he picks up his flute and the sounds of Bach’s Badinerie from Overture no. 2 in B Minor flood our raised ranch home.

Children counting out measures—

ta, ta, ti, ti, ta.

The tinkling of piano keys. The ticking of a metronome. Saxes playing in unison (my dad always played with his students).

Some people have comfort foods. I have comfort sounds.

Ever since I can remember, music was everywhere, all the time.

It was inescapable. Music is part of my DNA—both my parents were music teachers, singers, and dancers. When I was a baby, Mom and Dad would take me to their Westchester Baroque Chorus rehearsals. I’d cry unless they plopped me in the playpen in the middle of the room—I loved being around people, Mom would say. I’d coo along to their voices.

My mom told me that one time while they were singing Handel or Bach, I hit a really high note in perfect pitch, on key. At first they thought it was an organ key that got stuck. The group paused:

Did she really do that?

At home, when someone wasn’t playing an instrument, the stereo was on. Mom loves show tunes—

The Sound of Music, Purlie, My Fair Lady

. Some of her favorite singers are Roberta Flack, Frank Sinatra, Nat King Cole, Ella Fitzgerald, and Rosemary Clooney. Dad had eclectic tastes—he would listen to Tito Puente, Mongo Santamaria, Bill Withers, John Coltrane, the Beatles, the Temptations, the Staple Singers, gospel, classical, and salsa. He also loved big brass ensembles. Last year, at my daughter Jillian’s graduation, I recognized a piece Dad listened to all the time when I was a child. I smiled and thought,

Even though he’s not with us anymore, he’s here. I can feel him through this music.

I’d soak in all of the music—jazz, pop, classical, show tunes—my parents played in the living room. But in my bedroom I would listen to the pop station WABC on my little yellow transistor radio. This was at a time before music became compartmentalized, and I would hear all kinds—Elton John, Marvin Gaye, Chaka Khan, Teddy Pendergrass, Fleetwood Mac. I’d also listen to the Jackson 5’s

ABC

—the first album I ever bought. Everyone had that one. I loved every song and I would belt out the lyrics as I danced around my pale pink wallpapered room or jumped on my canopied bed.

Michael Jackson was my favorite singer and my first crush. He was so young and so talented. I drew a heart around his face on the

back of the album cover. I met him years later at Quincy Jones’s fifty-fourth birthday party in 1987. Ramon had worked with the Jackson family years before. I shook Michael’s hand. He seemed so slight, so fragile, so soft-spoken. What a difference between the childhood idol who I wanted to kiss and the man I just wanted to give a big, tender hug.

Growing up, we had a young girl, Diana, watch us before my mom got home from school. Then when I got older, I was a latchkey kid. The school bus dropped my brother, Chris, and me off right in front of the house. We’d head inside, race into the kitchen, and devour Hostess Fruit Pies, Ding Dongs, or Sno Balls (living just a few miles from the Hostess and Entenmann’s factories had its benefits—my dad would pick up the treats on his way home from school) and wash them down with Yoo-Hoo, grape soda, or milk. We’d play outside for a while and then I’d head to my room, flop on my white chiffon canopied bed, and do homework.

“Don’t answer the door. Don’t pick up the phone. Don’t talk to anyone,” Mom would tell us. Mom was always on edge, always suspicious, always expecting the worst.

But we weren’t latchkey kids for very long. Since Mom and Dad were schoolteachers just a few towns away from where we lived (Mom in Ossining, Dad in Elmsford), they’d usually be home a little while after we were. Then they’d start their second jobs—teaching music to local children. Our front door was always unlocked and there was always a car or two waiting in the driveway. My dad also taught students at their houses before he’d come home.

When I finished my homework, I’d throw open the screen door and run outside to ride my bike with Maura, my neighbor. We’d head to Elmer’s, the local five-and-dime, for some rock candy. Or I’d play tag or hide-and-seek with the neighbors or ride on our whirligig.

As the light dimmed, Mom would call us in for dinner. We’d sit

around the table, discussing the events of the day. Mom would tell us some funny stories about the kids she taught at Claremont Elementary. Sometimes Dad would pull out black-history flash cards. In between forkfuls of roast chicken or mac and cheese (our favorites), Dad would quiz Chris and me on icons and pioneers like Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, Malcolm X, Harriet Tubman, and Mary McLeod Bethune.

My parents would say, “We may be one of the only black families in the area—but we aren’t going to forget who we are.” They never stopped teaching!

My parents were hell-bent on making us as independent as possible, as young as possible. Since we were practically toddlers, we could tie our shoes and make our beds. My mom was so far from being a helicopter mom (and so am I). She believed that children needed to figure things out on their own without a mom hovering over them, waiting to pounce. If I asked my mom for something, she’d tell me to get it. If I ran out of clean clothes, she’d point to the washing machine.

When I was older and learning to drive, my father taught me how to change a tire. He handed me a jack and some lug nuts. “I don’t ever want you to be in a situation where you feel helpless,” he said. Years later, when I was driving home from Syracuse University, I had a blowout and was able to change the tire all by myself. I could still do it today if I had to.

Mom and Dad also wanted me to know how to do everything the correct way. Mom taught me how to properly set the table. She’d hold both hands out in front with the palms facing each other. Then using the tips of her thumb and forefinger, she’d make circles with her fingers. “Your left hand makes a

b

and your right hand makes a

d

.” She said this was the way I could remember that the bread goes on the left and the drink goes on the right.