You Have No Idea: A Famous Daughter, Her No-Nonsense Mother, and How They Survived Pageants, Hollywood, Love, Loss (13 page)

Authors: Vanessa Williams,Helen Williams

Miss Boley’s second-grade class

CHAPTER

7

I

was an eight-year-old girl in a heavy brown coat, holding my sisters’ hands tightly as we were forced to say the words that changed our world.

We stood in front of a stern-looking judge who presided over adoption court.

“Who do you want to live with?” he asked Sandra, Gretta, and me.

“Our grandparents,” we whispered, even though the thought terrified us.

We wanted to stay with our mother and baby brother, Sonny. Our grandparents were abusive people. (I found out years later that they could not have been our biological grandparents. I heard my grandmother say that she had had an accident and couldn’t ever have children. They must have adopted my dad. I believe his biological

parents were biracial—that’s why Vanessa and Chris have blue eyes. Milton and I have the recessive trait.)

I learned how to hold back tears at a young age. Even now, I rarely cry in public. Usually it’s when I’m all alone—in the shower or the bathtub. Then I let it all out.

We lived with my “grandparents” on the second floor of a two-family house in Buffalo and were told to call them “Momma” and “Daddy.” I didn’t know where my father lived. He worked for the railroads and made trips to Buffalo from time to time. But I knew exactly where my mother lived—in a house two blocks away.

I wasn’t allowed to visit her, see her, or talk to her. We never asked why. We understood that it was better not to ask.

All I knew is that my mother worked as a domestic. One day I was standing on the corner near my house. I saw my mother on the bus that the maids took to and from work. She looked right at me. I stared at her but didn’t acknowledge her. I didn’t wave. I didn’t even smile. I knew I’d get in trouble. I was terrified that someone was watching. Someone always seemed to be watching. I never said anything about it to anyone, not even my sisters.

Each year at Christmastime, a taxi drove to our house and dropped off presents from my mother—books and toys. I was allowed to call her to say thank you. I still remember the phone number—Cleveland 4880. My grandparents hovered over me as I spoke to her. I didn’t say anything more than thank you. I was afraid to speak.

My grandparents were always angry with us. Almost every day I got some kind of beating. I was hit with belts, leather straps, and rough, strong hands. Most times I’d have no idea what I did wrong. One day I was washing dishes and “Daddy” noticed I didn’t clean the bottom of the pot. He hit me with a leather strap for that. Another time I questioned something I had to do—what, I’m not sure. “Momma” took a nasal inhaler and shoved it up my nose while holding my other nostril closed with her fingers. I struggled to breathe.

I felt myself getting dizzy and about to lose consciousness. She finally let go.

“Daddy” worked at Bethlehem Steel. My sisters and I would get up at three or four in the morning and sit in a chair in the living room while he got ready for work. I don’t know why we had to do this. Again, something we dared not question. We’d sit there watching him, struggling to keep our sleepy eyes open. When he left, we’d get ready for school.

My real father would visit every now and then. He was charming, handsome, and a really good dancer. He’d tell me he was a hoofer. I remember going out for dinner and watching him flirt with the waitresses. When he’d visit, my father would ask me to sing “

O Mio Babbino Caro

” (“Oh, My Beloved Father”) from the opera

Gianni Schicchi

by Giacomo Puccini. It was his favorite piece of music and it became one of my favorites, too.

My father would breeze in and out of town. He’d stay for a short time and then before we’d know it, he’d just disappear. We had no idea where he went.

From the outside we seemed like a happy family. No one would suspect what was really going on behind the doors of 198 Hickory Street. I wore nice, stylish clothes. I was well-groomed. I went to school on time every day.

The one kind thing my grandparents did was to sign me up for piano lessons. It saved me. I found my escape in music. I would lose myself at the tiny spinet in the living room. I played viola and sang in the choir, too. My sisters and I performed as the Tinch Sisters at black churches all around the city. I played piano and sang songs—mostly spiritual music, such as “There’s a Balm in Gilead” and “Oh! What a Beautiful City,” which are still two of my favorite songs. I don’t know if we got paid. It was just something we did. We didn’t question it.

I studied so hard and so much that I always got high honors. I

skipped seventh grade. School and music were my lifeline to sanity. At that time most black students went on to a technical high school, but a teacher saw my potential and encouraged me to go to Buffalo’s East High School, which had a real curriculum and offered me a real future. I’d never considered college because no one in my family had gone, but my teachers there showed me that it was possible.

I entered State University of Fredonia on a scholarship when I was sixteen. I majored in music education. I was so happy to get away. I finally felt free.

One day I realized I didn’t have to follow my grandparents’ orders anymore. I started writing to my mother from college. I misspelled her last name on the envelope for years, always writing Doris Griffen when I should have written Griffin. She never corrected my mistake. I guess she was just happy to hear from me.

Years later, Milton, Vanessa, Chris, and I would make the eight-hour drive to visit my mother. We’d park in the back of the project where she lived behind a chain-link fence on Jefferson Street. Before we’d walk into the courtyard, we’d see her perched up in her kitchen window in apartment F, smiling down at us. She’d lived in the same apartment most of her adult life, so everyone knew her. She was the queen bee of the neighborhood until she died of complications from diabetes at the age of sixty-five.

Her headstone at Forest Lawn Cemetery in Buffalo reads:

GRANDMOTHER OF THE FIRST BLACK MISS AMERICA

.

She never did tell me why we lived two blocks away from her and had to pretend we didn’t know her.

Then again, I never asked.

“What a Difference a Day Makes”

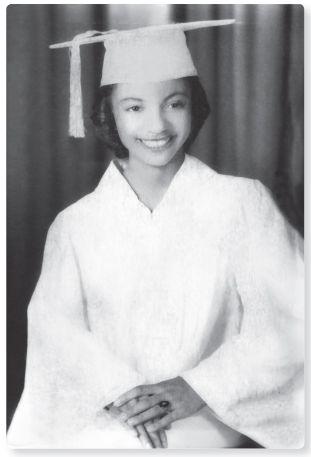

My mother, Doris Griffin, December 8 (my birthday)

“Midnight Train to Georgia”

My father, Edward Tinch

“I Will Survive”

World, here I come!

“Let the Good Times Roll”

The Tinch sisters: Gretta, Sandra, and Helen

CHAPTER

8

Vanessa had her secrets—I understood that. All children keep things from their parents. But there were times when she was an adolescent that I felt I didn’t know her at all.

—HELEN WILLIAMS

W

hen I was ten, family friends who had a daughter two years older invited me to visit their friends in Orange County, California. I figured my strict parents would never allow me to go away with Nancy and her parents. But Mom and Dad were busy traveling back and forth to the hospital to visit Uncle Artie, my dad’s younger brother. He was really sick with cirrhosis and the prognosis wasn’t very good. I suppose they figured they’d let me get away for a week and have an adventure. I was shocked but so excited. I’d never been on a trip without my parents.

Their home was about an hour south of Los Angeles and crammed with row after row of identical white stucco tract houses. The flat, dry land was filled with housing developments as well as construction sites for future developments. Thinking back on it now, it looked like the setting for a movie like

E.T.

or

Poltergeist

. It wasn’t exactly the California I had imagined.

The family we stayed with had two kids—Susan, who was eighteen, and John, who was twelve. Susan smoked, drove a car, and was the epitome of cool—at least to my ten-year-old brain. I always wanted to hang out with older kids. I couldn’t wait to be older, to be independent, and Susan treated us like we were older kids. She drove us to all the tourist destinations—Disneyland, Hollywood, the beach. She’d let us sneak a puff of her cigarette.

John was close to my age. As soon as I met him, I had a little crush on him. We all spent a lot of time playing outside when we weren’t sightseeing. One evening John and I wandered over to a construction site filled with big concrete pipes stacked on top of one another. We sat on a pipe and talked about school and friends.

Then John leaned in and kissed me. He had braces and they banged against my lips. It was a quick peck and then it was over. But it was thrilling for me—it felt like a big moment in my life. I had finally kissed a boy. We walked back to the house and I smiled the whole way.

Nancy and I slept in the den on two sofa beds. We whispered and giggled about my moment with John. I finally drifted off to sleep, dreaming of my kiss.

I don’t know how long I was asleep—minutes? Hours? But at some point, the accordion door to the den slowly opened and Susan crept in. I couldn’t figure out why she was in our room in the middle of the night.

Susan whispered, “Be quiet.”

She told me to get out of bed and lie down on the rug.

I was confused. I looked over at Nancy, who was sleeping soundly. Are we going to play a game? As I tried to make sense of why this older girl wanted me to lie on the rug, Susan pulled down the yellow bloomers of my cotton baby-doll pajamas.

“What are you doing?” I asked.

“Don’t worry—it’ll feel good.” I lay there paralyzed as she moved

her tongue between my legs. What was going on? I didn’t speak. She kept at this for I don’t know how long. But it felt good, weird, and definitely wrong—all at the same time. She slid my bloomers back up and whispered: “Don’t tell anyone.”

I watched her as she crept back out. I climbed into my bed, still tingling at ten years old, trying to figure out what had just happened. Why had she done that? Was it something teenagers did to each other? Only girls? I thought it had to be something bad—why would she have told me not to tell anyone?