You Must Change Your Life (11 page)

Read You Must Change Your Life Online

Authors: Rachel Corbett

He didn't make it far before he noticed, to his pleasant surprise, that the women in white were following him. Fresh off the dance floor, their cheeks were pink with laughter and they radiated heat. Rilke pushed open his window for them and they sat to cool themselves at the sill. As their breathing slowed, they turned their attention to the moonlight. Rilke watched them, no longer “disfigured” by their revelry, start to gaze deeply into the night. He saw in this moment a portrait of transition, framed by the window. It was as if Becker and Westhoff had transformed from girls into observant artists in a single second. After they left, the vision of the girls moved him to write a few lines of verse in his diary, where he described them “half held in thrall, yet already seizing hold . . .”

Rilke came to the conclusion that the life of an artist should ideally begin at the precise moment when childhood ends. When one is open to the world with the unexpectant awe of a child, images come freely

streaming in, like the moonlight to Becker and Westhoff's eager eyes that night. But the poet now had to learn how to channel these images into art, and Worpswede seemed like the best place to do it. “The Russian journey with its daily losses remains for me such painful evidence that my eyes haven't ripened yet: they don't understand how to take in, how to hold, nor how to let go; burdened . . . And if I can learn from people, then surely it is from these people, who are so much like landscape themselves.”

Rilke first sought out Otto Modersohn, a tall, red-bearded painter who was, at thirty-five, older and more established than many of the other artists at the colony. Rilke found his studio lined with moody landscape paintings and display cases filled with dead birds and plants, which he used to study color and the way it faded. Rilke told him about his desire to experience the world through the point of view of a visual artist, and Modersohn agreed that young people ought to approach life as receptively as bowls. They should not expect to be filled with answers, but, if they were lucky, with images, he said.

From Modersohn's studio, Rilke went on to visit Paula Becker. Discovering how easily they “made toward each other through conversations and silences,” he found himself becoming more attracted to the “blond painter” than the “dark” sculptress. But Clara Westhoff's art continued to interest Rilke more than Becker's (as did sculpture in general over painting, which he once derided as “a delusion”). Westhoff was drawn from the start to the poet's boyish blue eyes, which distracted her from some of his less appealing features. Meanwhile, a quiet courtship was developing between Otto Modersohn and Becker. He was already married, but when his wife died suddenly that year, the pair got engaged. After that, Rilke turned all of his attention to Westhoff.

His attraction was rooted primarily in respect for her work. Her reserved nature made it more difficult for a romance to develop. But their intimacy grew gradually over the coming weeks as she began to teach him about sculpture and told him stories about studying with Rodin. Afterward he would return to his room and recount these conversations

in the pages of his journal. Once he suggested they cowrite an essay on Rodin. Over time, their rapport turned more tender, and his prose turned into poetry. He began writing verses about her strong hands, a feature that Rilke had always admired in artists, for he believed a sculptor's hands could remake the world.

AFTER SIX WEEKS,

Rilke left Worpswede for Berlin. He had never intended to join the colony permanently and didn't want to overstay his welcome as a guest.

In his absence, Rilke and Westhoff stayed in touch through letters. He was so impressed by the descriptive imagery in her writing that sometimes he felt his responses were merely rephrasings of her experiences. In one remarkable passage he confessed his desire to load “my speeches with your possessions and to send my sentences to you, like heavy, swaying caravans, to fill all the rooms of your soul.”

In February, Westhoff visited Rilke in Berlin. He did not idolize her the way he had Andreas-Salomé, but perhaps that was part of the appeal. He hinted once in his diary that the relationship with Andreas-Salomé had emasculated him. “

I

wanted to be the wealthy one, the giver, the one offering invitations, the master.” Yet he felt time and again that he was only “the most insignificant beggar” to her. He had nothing to offer his brilliant older lover, but this “maiden” Westhoff never seemed to doubt him. Her admiration felt refreshingly pure and uncomplicated.

Rilke and Westhoff surprised everyone with their engagement announcement the following month. When they returned to Worpswede to share the news with their friends, Otto Modersohn wrote to Paula Becker asking if she could guess who he saw that day: “Clara W. with her little Rilke under her arm.” By then Becker was away at a cooking school in Berlin, having submitted to pressure from her father to devote herself completely to her fiancé. He told her in a rather depressing birthday letter that she ought to “have his welfare constantly in sight” and not let herself “be guided by selfish thoughts . . .”

By March, Becker was miserable. “Cooking, cooking, cooking. I cannot do that anymore, and I will not do that anymore, and I am not going to do that anymore,” she wrote to Modersohn, warning him, “You know, I can't stand not painting much longer.” Becker promised herself that she would wait to have children until she had fulfilled her own dreams. But she feared that Westhoff was not so strong-willed. Becker predicted from the start that her friend's new union would prove to be Westhoff's sacrifice alone. Becker had felt Westhoff slipping away ever since she met Rilke. Why couldn't they all live together again as a community, like they'd always dreamed? Becker wondered. “I no longer seem to belong to her life,” she wrote. “I have to first get used to that. I really long to have her still be a part of my life, for it was beautiful with her.”

The news of the engagement dismayed Andreas-Salomé even more. Her objection did not stem from jealousy, she claimed, but from a concern that the commitment would stifle Rilke's creativity just before it blossomed. She also knew he wasn't mature enough to shoulder the responsibilities of a family. She wrote him a “last appeal” urging him to reconsiderâor else not to contact her again. At the last minute she enclosed a concession, writing on the back of a milk receipt that she would in fact see him if he was desperate, but only in his very “worst hour.”

The ultimatum was harsh, but not unfounded. Family had been a mythology to Rilke ever since he was born. He had embodied his mother's fictions as a daughter, as fake nobility, and now he was concocting his own domestic fantasy. He once described in a letter to Westhoff his baroque mental picture of marriage: He was standing at a stove, cooking for her in dim lamplight. There would be honey gleaming on glass plates, cold ivory slices of butter, a Russian tablecloth, a rocky loaf of bread, and tea that smelled of Hamburg rose, carnations and pineapple. He would drop lemon wedges into the teacups to “sink like suns into the golden dusk.” There would be long-stemmed roses everywhere.

In reality, Rilke was eating oatmeal every night. But he believed that marriage was part of becoming a man, and that a child had to first

become a man before he could be an artist. Plus, it seemed like everyone in their Worpswede community was getting married that spring: Heinrich Vogeler had just wed a young woman from the village, Martha Schröder, and Becker and Modersohn were engaged to marry the following month.

Rilke married Westhoff at the end of April 1901, in her parents' living room in Oberneuland. He told a friend, with no shortage of condescension, that “the meaning of my marriage lies in helping this dear young person to find herself.”

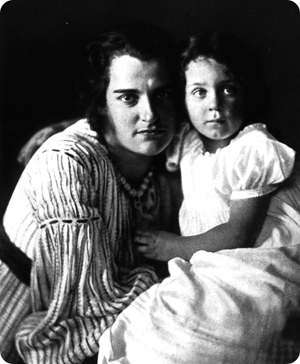

Rilke in Westerwede in 1901, the year he married Clara Westhoff

.

The following month they moved into a thatched-roof cottage in Westerwede, a village neighboring the artist colony. At first, the dead-end road isolated the couple in their work. Over the next year, Westhoff filled the house with sculptures and Rilke wrote a monograph on five of the Worpswede painters. Then, in one week, he completed the second part of the

Book of Hours

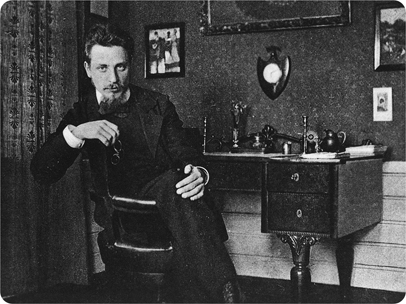

. But their quiet solitude was soon interrupted when Westhoff found out she was pregnant and, by the end of the year, gave birth to a daughter. They gave her “the beautiful biblical name” Ruth.

For all the molten emotion that poured from Rilke's pen over the years, he managed to describe his daughter only in surprisingly vague abstractions. “Life has become much richer with her” was among the most effusive lines he came up with. To Rilke, Ruth completed the family unit and marked a necessary transition into maturity. But the unsayable hungers and tears of this “little creature” bewildered him.

A few months after Ruth's birth, in February 1902, Westhoff wrote to Becker about how she felt “so very housebound” now. Gone were the days when she could just pick up a bicycle and pedal off for an afternoon in the sun, bringing whatever she needed on her back. “I now have everything around me that I used to look for elsewhere, have a house that has to be builtâand so I build and buildâand the whole world still stands there around me. And it will not let me go . . . Therefore the world comes to me, the world which I no longer look for outside . . .”

The letter enraged Becker. It wasn't so much what she said, but how she said it. Westhoff's words didn't sound like her own. They sounded like Rilke's. Becker tore into her friend with all the hurt and resentment that had been building for months. “I don't know much about the two of you, but it seems to me that you have shed too much of your old self and spread it out like a cloak so that your king can walk on it.” Why wouldn't Westhoff wear her own “golden cape again”? she wondered.

To make matters worse, Westhoff had forgotten her friend's birthday. “You have been very selfish with me,” Becker wrote. “Must love be stingy? Must love give everything to one person and take from the others?” Becker then turned her pen against Rilke. Enclosed in the same letter she wrote, “Dear Reiner [sic] Maria Rilke, I am setting the hounds on you. I admit it.”

She begged him to remember their communal love of art, of Beethoven and the happiness they once shared as a little family in Worpswede. She thanked him for sending his latest bookâit was “beautiful.” But in the next breath she insulted his writing: If he was going to respond to her letter, “please, please, please, don't make up riddles for us. My husband and I are two simple people; it is hard

for us to do riddles, and afterward it only makes our head hurt, and our heart.”

Two days later, Rilke fired back a withering retaliation. He told Becker that her love must be too weak for his new wife, for it had failed to reach her at a time when she needed it most. Was Becker really so selfish that she could not celebrate her friend's newfound happiness? Why did she refuse to acknowledge the sacrifice he and Westhoff had made in order to be together?

He reminded Becker that she herself had always praised Westhoff's solitary nature. It made her a hypocrite to chastise her friend now for the very quality she had always admired. Why not “rejoice” in anticipation of the time when Westhoff's “new solitude will one day open the gates to receive you? I, too, am standing quietly and full of deep trust

outside

the gates of her solitude,” he said. Then, authoring what would become one of his most lasting mythologies about marriage, Rilke added: “I consider this to be the highest task of the union of two people: that each one should keep watch over the solitude of the other.”

Becker surrendered. No matter how self-serving Rilke's rhetoric was, one could hardly compete with it when rendered this majestically. Becker responded only in her diary, writing of the inconsolable loneliness she had felt during the first year of her own marriage and that she had believed Westhoff was the only person in the world who could alleviate it. Now she had to face the painful likelihood that their paths would never cross again.

As Becker slipped into depression, Modersohn blamed it on Rilke and Westhoff. He complained in his journal that they never bothered to ask his wife about her work, nor did they ever visit. Now Rilke had displayed an inexcusable arrogance with his claim that Becker should remain on the other side of Westhoff's gates until Rilke's “lofty wife . . . opens them up,” Modersohn wrote. What about Becker? “The fact that

she

is somebody and is accomplishing something, no one thinks about that.”

Selfish or not, Rilke was not exaggerating the hardships facing his new family in those days. His fatherhood status had disqualified him

from the college stipend he had been receiving from his uncle Jaroslav's estate. He wasn't making much money from his writing, either. Critics had panned his recent story collection,

The Last of Their Line

, and bookstores were scarcely selling it.