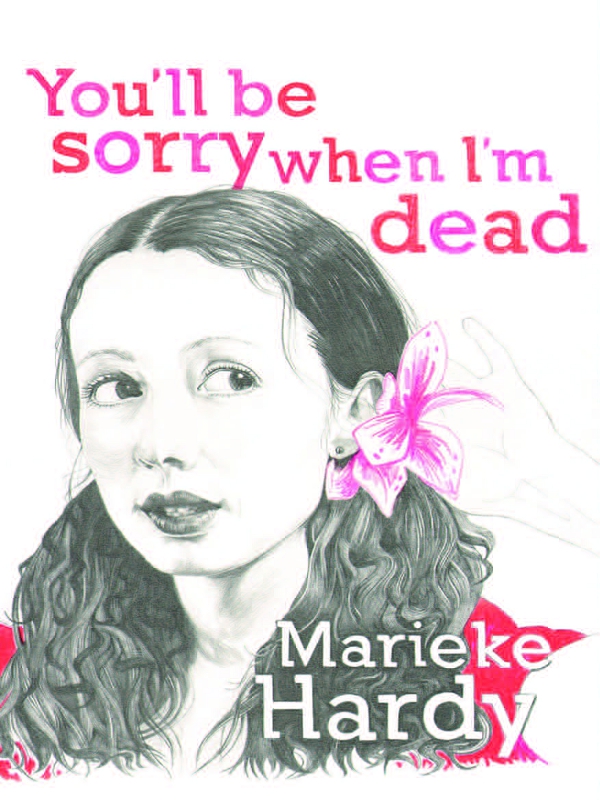

You'll Be Sorry When I'm Dead

You'll be

sorry

when I'm

dead

Marieke Hardy

First published in 2011

Copyright © Marieke Hardy 2011

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian

Copyright Act 1968

(the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

Sydney, Melbourne, Auckland, London

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

| Australia | Â |

| Phone:Â Â | (61 2) 8425 0100 |

| Fax: | (61 2) 9906 2218 |

| Email: | [email protected] |

| Web: | www.allenandunwin.com |

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available

from the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 74237 726 1

Set in 13/16 pt Bembo by Post Pre-press Group, Australia

Printed and bound in Australia by Griffin Press

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Gabi

Contents

An afterword by my ex-boyfriend Tim

Marieke Hardy is my daughter. If you are reading this, it means her new book has been published.

As the writer of this book she has used the real names of people she writes about.

I argued long and loud with her that it is âbetter', or rather âsafer', to fictionalise names and events in one's writing to avoid hurting the real peopleâand indeed the writer!

Then I have to remember that her grandfather used a fake name of a real person and even changed what happened to them yet still got into a mess of trouble.

Her grandfather, my father, Prank Hartley (not his real name) wrote a novel entitled

Powder without Chlorine

(not its real name). In this novel he followed the life of a fictional character who was based on a real person, Ron Rebb (not his real name). In the book the writer had the fictional character do things that the âreal' character did not do.

Was it legitimate fiction or was it an attack on a real person?

The court found for the writer. It was a work of fiction. The argument lives on.

My father also wrote himself into another book as FJ Borky (not his real name), a struggling left-wing writer hiding from debt collectors. This was alarmingly close to the truth.

It must be clear to all but the most obtuse among you that real versus fictional names can be a nightmare not only for those written about but for the writer whose relationships can be put under real strain.

I admire the talent of my daughter and love her writing.

It is truthful, emotionally honest and revealing of the human condition. Yet could she not achieve the same ends without the real names?

But she is a wonderful writer for all that and I will read this book when it is delivered to me where I currently reside.

Alwyn Hadley (not my real name)

Somewhere on a beach near Bridgetown, Barbados

(I no longer appear in public.)

At the age of eleven I decided with no small sense of certainty that when I grew up I wanted to become a prostitute. I was so convinced by this as a path of righteousness I felt comfortable enough announcing my intentions to not only my close circle of girlfriends, but also the elderly Vietnamese couple who ran the local milk bar. I can't recall their exact reaction at the time, but they were usually very supportive of my scamp-like antics and, besides, their English wasn't the best so they very likely nodded and smiled and gave me a free Wizz Fizz, which seemed to be their go-to response with the more wayward neighbourhood children.

For some reason my parents weren't as excited about the idea. Attempts were made to talk me around, but I was a child of strong will.

âMum . . . Dad . . . I appreciate your concerns,' I told them one night over a traditional Friday fish-finger dinner, âbut this is just how it is. Being a prostitute is my dream. I wish you'd understand that and show some support.'

Musical theatre is entirely to blame for this sudden and arresting career decision. Musical theatre, combined with those first illicit throes of nocturnal explorations beneath an embroidered doona; awkward, arching contortions in flannelette pyjama pants. I dreamt of A-ha's Morten Harket and his âconfusing' leather bracelets, possibly setting the scene for a future interest in BDSM.

The sum of masturbation and musical theatre was almost crippling in my caseâit seemed I leapt overnight from cheerily faking Xavier Roberts' autograph on the buttocks of cut-price Cabbage Patch Kids to plotting an illustrious career as an underage streetwalker. Performances of

Godspell

and

Jesus Christ Superstar

should be forward announced with a grim warning for young ladies: abandon hope all ye who enter here. Musicals are sticky and dangerous, and they lead by tempting example. The seamier characters in the cast always get the best songs, the rudest, most inviting dance numbers, the most enticingly risqué costumes. Productions like

Sweet Charity

and

Cabaret

, where rows and rows of intensely beautiful, saucy whores, decked out in hotpants and fishnet stockings and bowler hats, high-kick their way around wooden chairsâwhich seems, in hindsight, a misguidedly cheery response to their presumably bleak working conditionsâinevitably make prostitution appear an exciting profession. If selling one's soul to the devil involved face makeup and a sequinned bow tie, as a child I was mystified as to why parlour madams weren't beating off potential employees with a stick. Perhaps if veterinary nurses were allowed to wear feather boas and false eyelashes I may have been equally enamoured with the idea of sticking my hand inside dogs' vaginas.

As a pre-pubescent, masturbation was a revelation; a ticket out of dullsville directly into the sticky, pulsating, heady area of grownups. Somewhere along this naïve and playful voyage of physical discovery I decided that if touching oneself in the lap area felt so good it was only natural that prostitutesâ who were touched on their laps a great deal, if schoolyard rumours were to be believedâfelt good all day long. Combined with the glamour of musical theatre, it was a no-brainer.

Suffice to say I never quite achieved the dreamâdespite what you may read in the Murdoch pressâand as an adult I ceased aspiring to be a prostitute and instead became fixated on whether my boyfriends had slept with one. I pushed and prodded my long-suffering partners; bullied them in those easy, unguarded moments that creep in during lengthy afternoons touching toes beneath beer garden tables. I wanted to know obscene details and lurid insights, to get the inside story on what exactly happened when you were alone in a room with someone you'd just

paid for sex

. Who made the first move? What would be your opening gambit? Did anyone fumble with a bra? Was there even a bra?

âYou can tell

me

,' I would say with a general air of what I hoped was cheer and trustworthiness. âI'm not

worried

. I'm not going to

judge

you.' Whether the men involved had been burnt by such breezy assurances by girlfriends in the past, or had lived a life remarkably sin free, they were nonetheless too smart to buy into my games and left me anecdote-poor and hungry for knowledge. I still wanted to understand what went on behind the velvet curtain, or smeared sliding door or, in the case of some less salubrious outer suburban businesses, bullet-riddled flyscreen. Red lights and buzzing fluorescents and lamps with shawls draped over them, value packs of lubricants, massage oil that smelt like cupboards. My assumptions about the world of prostitution were cartoonish at best.

Certainly strip clubs had always been accessible, but I'd never seen the point of them. All that money being thrown around in sticky wads, just so a frightened-looking meter maid might indelicately shove her gusset in your face. There was no touching the talent, and if a chap got even the slightest semblance of a hard-on he was tapped on the shoulder and politely asked to leave. Why bother? The thought of all those men standing around in meaty clumps, sniggering and snorting and gaping open-mouthed, not knowing where to put their fingers or their beers, then climbing into their cars with straining erections and heading home for a sad diddle in the shower seemed simply ludicrous.

The last time I'd been to Melbourne strip club Spearmint Rhino my friend Gen had drunk the bar clean of tequila and spent a disturbing amount of time in a dark corner making out with a stranger who was the spitting image of Shane Warne.

âI don't have my glasses on. Is he hot? Should I go home with him?' she slurred to the rest of us during a break from frantic necking. She was wearing a peaked cap with the words

BEER SLUTZ

emblazoned across the front.

âGen.

No.

'

Gen winked and nodded at the same time, an action we would have thought physically impossible given the fact she'd just spent the last five minutes trying to eat a discarded peanut off the floor, and lurched off back in the direction of Warney and his unimpressed pals. We lost her for a little while after that, and became swept up in the typical social awkwardness that abounds when a group of inner-city wankers visit a strip club âironically'. We swung between snidely making fun of the stripper outfits, or acting as private ventriloquists and giving the dancers comedy voices (âWhere did I put my Kilometrico? I fancy doing the cryptic once I'm offstage. Oh look, it's up here' etc.) and then lapsing into long, strained silences the moment something undeniably erotic occurred.

We were reminded of Gen's presence about forty minutes later when we saw her wedged smudgily between a pair of grim-faced bouncers who were in the process of frogmarching her to the exit. Obviously we rushed to defend her honour, something we perhaps should have done about three hours before when she'd made her first louche approach to the Spin King.

âWhat the hell's going on?'

The bouncers looked at us disparagingly.

âYou with her?'