You'll Be Sorry When I'm Dead (14 page)

On

Neighbours

I played a small-time crook named Rhonda Brumby, living proof that ten years after Russell Crowe's appearance the writers were still fairly creatively challenged when it came to naming characters. Rhonda Brumby was fresh out of âjuvie' and full of the sort of cartoonish bad girl swagger usually seen on cockney skanks parading around the set of

EastEnders

employing rhyming slang instead of real words. I actually got to say the line, âDon't sweat it, bossâI've got the old bag wrapped around my little finger' and nod menacingly. I was running a stolen goods racket out of Marlene's antique shop (Ramsay Street was a badlands in those days) and eventually sent packing after a hair-pulling scrag fight with a character called Bianca Zanotti. The inmates of Wentworth Detention Centre had nothing on our tussle. We slapped at each other, shrilly squealing things like âOh yeah? Well how do you like this, moll?' until I tumbled to the carpet, humbled and subdued and ready to be packed back to reform school where I would presumably Turn Over a New Leaf on the off chance my agent could negotiate a returning role.

I had sat around the

Neighbours

green room with the other actors, who were convinced they'd be able to throw together a markedly improved script in a pinch and had no issue whatsoever with undermining the tireless plotting work of their story department. I had rolled my eyes in a comradely fashion over the clunky dialogue and D-grade storylines, and was thus mortified when a month or so later I landed a job as a storyliner and sat in the writer's room listening to the script department make equally poisonous fun of the actors. It was an all out faction war, with the major casualty being the show itself. Tauntingly, the actors would change all-important lines whilst on set, breezily throwing away plot points on the spur of the moment in order to slot in private jokes. In retaliation, the storyliners would conjure up increasingly absurd and humiliating scenarios for the actors to play out. The end result was a show full of characters wearing ludicrous things like fishing waders and lampshades whilst trading adlibs and making no sense whatsoever.

The production company responsible for

Neighbours

decided in a burst of inspiration to install the writing department out at the studio for one day a week, so the actors could have access and discuss ideas for stories and character arcs. This should by all means have been a seamless exchange and friendly, bridge-mending process and probably would have been if the majority of actors weren't so blindly ignorant of the scripting method itself. They'd come to us, one by one, with poorly hidden agendas about getting kissing scenes with cast sexpot Kimberly Davies (âI just think my character would really

connect

with Annalise as a

person

') or wildly inappropriate storylines about heroin addiction and AIDS. Actors always wanted to play heroin addicts or AIDS victims, simply so they got the chance to rub red makeup under their eyes and deliver dialogue in dramatic, award-winning gasps. One of the very pretty male leads came to see us for a long discussion about where his character was going and how ready he was for some truly meaty storylines.

âI just . . . I want a chance to stretch myself, you know? Reallyâgo to some dark places,' he said to us, gazing through the glossy, floppy fringe currently sending thousands of

TV

Week

readers into gusset-dampening swoons.

We took him at his word and spent the next week plotting a story that was, for

Neighbours

circa 1996, relatively dark. We gave him cancer. It was television cancer, yes, which meant that it would probably never be properly named or treated and that it would only last for about eight weeks before everybody moved on to worrying about Harold Bishop's upcoming tuba recital, but for an actor on a 6 pm soap it was at least a chance to show off some good âstaring death in the face' performing. Characters with cancer get to cry, punch paper thin walls in fits of anguish, and scream things like âTell it to me straight, Doctor Karl. How long have I got?' before collapsing in a dramatic faint. If he wanted dark places, this story had âSilver Logie' written all over it.

The next time we all met out at Channel Ten, we pitched the story to him. He listened to the whole thing impassively before chuckling quietly to himself as though there had been a dreadful misunderstanding yet we as simpleton writer folk weren't to know any better.

âI didn't say,' he explained slowly, just to make sure we were taking it all in, âthat I wanted to

cut my hair.

'

As he left the room he glanced at me, annoyed and hurt that as a fellow actor I hadn't helped him out in some way; understood that when he'd said âdark places' he'd actually meant kissing scenes with Kimberly Davies that went for longer than three minutes. There was the sense that as somebody who had worked alongside the cast I should have been better equipped to fly the flag for them behind enemy lines.

I had seen the looks on their faces as they entered and noticed me there at the table, sitting with the much maligned script department and plotting the next degrading episode in their career.

Traitor

, I could feel Lou Carpenter thinking.

Scab

.

Suck it up, Lou

, I thought meanly in return, unwilling to be tarnished.

You should hear our nickname for you when the producers

leave the room.

It was the first time I had felt a real chasm between myself and the acting world and I felt a stab of regret, as though I may have been making a dreadful mistake and leaving my people behind. Every time I sensed myself veering away from the punishing treadmill of auditions and headshots I made a desperate grab for the nearest role available, no matter how demeaning. I accepted walk-on parts as feral protestors, voice-overs for Cadbury's. I even spent five fairly gruesome evenings covered in fake blood screaming hysterically at the aftermath of a car crash for a road safety commercial about dangerous driving. My character was a daffy passenger who distracted her chum to the point where our vehicle ploughed into another car and killed its driver, leaving a crying baby motherless. Our tagline: Concentrate or Kill.

The whole world of film sets was intensely familiar and difficult to leave. Sedentary, conventional childhoods involving tennis lessons or catching the bus to school were things other, more well-adjusted friends from normal families had experienced. For months at a stretch I had lived on location, away from home. Colac, Echuca, Broken Hill. I had grown up too fast. I had lived in hotel rooms with scant regard for the discipline of schoolwork, surrounded by adults at all times. I had drunken nights with crewmembers and been stung by the insidious politics of the production office. On location, there was a reckless âschool camp' feelâeverybody went to the pub after wrap and cheated on their spouses. What happens on tour, etcetera. It set an unhealthy foundation for relationships for years to come, and that transient sense of believing that you can inhabit and abandon a family within a matter of months.

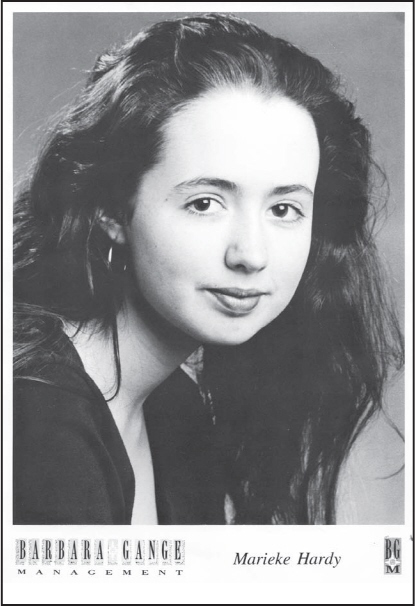

Then the roles began to fall away. And over time I stopped chasing them with that panicked feeling of missing out. I no longer went to castings. I stopped reading scripts. My loyal agent held on for a valiant number of years before she realised that I hadn't updated my headshot since I was seventeen and there was utterly no point sending a twenty-five-year-old along for the role of pre-teen runaway Amber âGiggles' McCoy.

Yet an acting past haunts you in the way no other shameful previous professions do. Loose on a wild weekend in Surfers Paradise, a topless barmaid in a strip joint stopped me as I walked past.

âExcuse me,' she said, little brown boobies jiggling beneath the disco lights. âWeren't you on

The Henderson Kids

?'

It wasn't as bad as the blindly offensive opener âDidn't you use to be . . .' but was awkward regardless. At least she had a reference point. For a long time people would stand in front of me, trying to figure out where they knew me from. âYou went to Deepdene Primary School, right?' they would ask, certain that they knew me from childhood, a familiar face amongst the sandwich triangles and asphalt. âNo . . .' I would say politely, affecting a mirroring puzzled look, and implying with murmurs we'd figure it out together one day in the near future and marvel at how we'd ever managed to let such an obvious fact slip our minds.

Twenty-five years after the shoot, the cast and crew of

The Henderson Kids

held a reunion party. Everybody gathered together on a freezing Melbourne Sunday afternoon to compare stomachs and breeding capacities, in that way adults do. There were all the former child actors of the cast, jostling noisily in a bar, looking tired, looking smeared with drink, looking, if you squinted, a little like the fresh-faced stars of a 1986 television show who had been filled with air and then deflated again, like a packed away bouncing castle. Some were still acting. Some presented

Play School

. Some were addicted to heroin. We exchanged comradely smiles and sympathetic stories of the dire state of the Australian film and television industry, or at least the parts of it that no longer employed us. Behind us, on a projector screen, were images of our more successful and wholesome past. Freckled, buck-toothed, ringleted, these kidlets from promotional shots in happier days rotated slowly like relics from a happier world.

I felt for those still in the game. They seemed lost. You could see them trying not to look at the younger, better-looking versions of themselves as they talked up their walk-on role in the MTC production of

Uncle Vanya

, or three-week guest spot on

Packed to the Rafters

.âI just did a corporate video with Iain Hewitson,' said one haggard gentleman, who had played a member of feisty onscreen BMX gang the Brown Street Boys. I felt suddenly grateful for that chasm between my old life as an actor and the one I led now, doling out poisonous barbs and settling debts with people like Elissa Elliott and Peter Phelps from the privacy of my own home. With writing there is an inherent freedom, the ability to be your own boss and keep working when nobody is watching. More importantly you can write in your underpants. You can act in your underpants too, though I'm fairly certain my days of acting in underpantsâmy own or anybody else'sâare over. Perhaps I'm still just waiting for that phone call from my agent, the one telling me the perfect role has finally arrived and I'm to drop everything at once and claw my way back to D-grade stardom.

âYou'd be crazy not to take it,' she will say. âIt's a heroin addict with AIDS. You were born to play this part, Marieke. It's time, time to return to the fold.Your people need you.'

My life felt fairly beyond repair when it was suggested to me that Dan move in.

I was in a bad way. I cried pretty much every time I spoke to someone on the phone. I would take the dog for a walk and try to hold back tears through the streets of Brunswick, in big gulping graceless hiccups. I would start crying at the Video Ezy on Lygon Street when they wouldn't allow me to rent

Four Lions

because I had accumulated too many fines. The workers there eventually started looking sorry for me every time I walked through the door, knowing that without fail within about twelve minutes I would start crying again. One of them, a boy with an eight gauge lobe piercing, began saying âhere she comes' under his breath when I entered. I left every time filled with utter despair. I couldn't even muster the dignity to blow my nose.

âPerhaps we can come over tonight,' my mother would say, worried that I was going to spend the rest of the evening listening to Captain Beefheart records and jauntily slitting my wrists in the bath. âWe could bake a cake.'

I was thirty-four years old. I did not want my parents driving from East Hawthorn to Brunswick to help me

bake

a cake

.

âI'll be fine,' I said, through a bout of noisy, un-fine tears. âI'm just going to . . . sit and look at a candle or something and wait until I go to sleep.'

I had briefly considered killing myself but spent four hours trying to figure out who would feed the dog while I was lying on the bathroom floor choking on bloodied ribbons of my own puke and in that time lost my enthusiasm for the idea. And something a similarly harrowed companion had once said to me kept rolling through my head like the sea.

âI could never commit suicide,' he whispered in the dark. âBecause then I would never find out who or what was around the corner. And I am by nature a very curious person.'

A broken heart was responsible for it all of course, the fucker, the worst kind of internal tsunami. I had until then considered myself immune to the platitudinous nature of heartbreak, and was not known for being outwardly emotional. When something bad happened I would study it at arm's length with a puzzled and autistic expression, as though pain and hurt were simply a jagged little Rubik's Cube, waiting to be solved. If people cried in front of me I got nervous like Rain Man and started pacing. Then suddenly it swept through, heartbreak in its big black wave, obliterating everything in its path. I had overnight packed my bags and joined the community of the emotionally stranded. Worse, I had become a spontaneous weeper.